Australia’s shadow banking sector: Mum and Dad

THE number of parents lending their kids cash for both deposits and mortgages is out of control. And it could harm our economy.

HAVE Australia’s youth finally come up with a brilliant ploy to reverse the intergenerational inequity of the housing market?

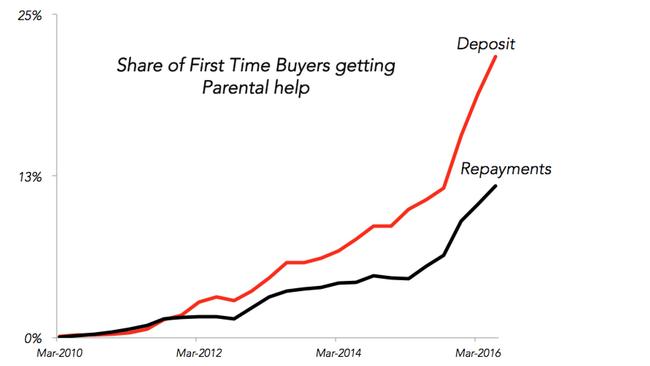

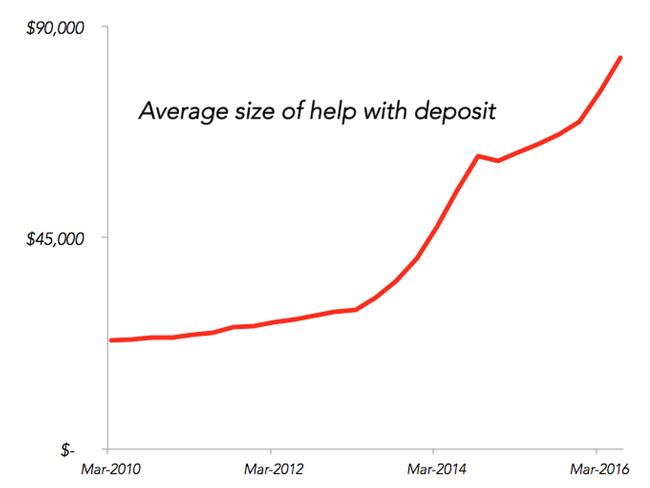

This graph certainly suggests so. Asking mum and dad for help to buy a house is surging. Parents are not only shelling out for deposits, but also helping kids pay back their loans.

This is wonderful for some young Aussies. But not everyone is in the same lucky position.

Not all Australian families have the resources to finance a new home for the kids. While 10 per cent of Aussie households have more than $1.8 million in total assets, another 10 per cent have less than $10,000. So whether you can wring an $80,000 deposit out of the olds depends a lot on who they are.

If you have a sole parent, the chances are worse still — poverty levels are higher and wealth is lower among sole parent households than for couples with children.

The housing market is already tough to get into. Most first homeowners grants are gone but prices are still rising — parental contributions probably only make prices higher.

HELICOPTER PARENTS WITH HELICOPTER MONEY

But the bank of Mum and Dad could be doing more than making Australia’s housing market increasingly unfair. It could be making it more unstable.

There are two main risks in parents turning themselves into home lenders.

1. When the parents want the money back.

2. When they don’t want the money back, but they’ve got the kid into a home they can’t really afford.

Either way, it adds a layer of complexity into the financial system by loading kids up with money banks might not know about.

Banks are limited by lending rules. They may bend or break these rules from time to time but they mostly adhere to them. Overgenerous parents, meanwhile, have no idea how to do prudential management and could easily overextend their kids.

The problems only multiply when the money the parents are accessing comes from refinancing their own homes — creating a cavalcade of apparent property wealth that could all be at risk in case of lost earnings or a broader property downturn.

While the scale of parental lending remains quite modest for now, the 2014 Financial Systems Inquiry made direct mention of the way risks emerge outside the main financial channels:

“History tells us that the next financial crisis never looks quite like the last. It is not possible to know for certain where systemic risks will arise; however, it is perhaps more likely that they will emerge outside the prudentially regulated part of the financial system, such as in the shadow banking sector, where oversight is more limited.”

When we talk about shadow banking, we mostly talk about China, where close family connections and black market money lenders create an elaborate network of financing that rivals the scale of China’s banks. Over there, shadow banking is a real and present danger to the health of the economy.

Australia’s problem is not at the same scale. But for people already worried about the housing market and Australia’s growing private debt pile, it adds another straw to the camel’s back.

With the US contemplating further interest rate rises within months, it is only a matter of time before Australia’s period of record low rates comes to an end too. And an apartment supply surge could also put Australia’s house prices under pressure. If that happens, every overextended borrower could help contribute to a price slide becoming a price crash.

Jason Murphy is an economist. He publishes the blog Thomas The Thinkengine. Follow Jason on Twitter @Jasemurphy