Aussie house prices: RBA speech fuels confusion about whether prices will increase or drop

Three things have combined to create a housing market that’s unpredictable and potentially volatile. The ripple effect could impact us all.

Is Australian housing going up or down? The big problem with the housing market right now is that even the Reserve Bank doesn’t seem to know.

The RBA is in charge of interest rates and they are supposed to keep a handle on unsustainable debt. But they seem unsure or even in denial about what’s happening in Australian housing right now.

The RBA Governor fronted up at Australia’s Parliament House during the week and responded to questions from the economics committee. What was going to happen with housing, they asked?

“It does appear that the trend is towards higher housing prices at the moment, and that shouldn’t surprise us. Lower interest rates do mean higher asset prices,” said RBA Governor Philip Lowe. That seemed clear. It was also consistent with a recent major speech by a Reserve Bank official which said that boosting asset prices was meant to make households richer so they spend more.

But moments later, the RBA Governor pointed out weak population growth, rental vacancy rates peaking in Sydney and Melbourne apartment markets, and falling rents.

“While ever that remains the case, it’s hard to see a generalised widespread increase in housing prices,” he said. I was puzzled. That seemed to imply he didn’t expect house price rises.

RELATED: Test after ‘embarrassing’ money mistake

To add to the confusion, he emphasised the point that population growth is key.

“Across the country as a whole, with population growth so low, I’m not expecting to see big increases in housing prices.”

Are prices flat? If so that could make it a good time to save a bit more in order to buy later. But the Governor continued to mix his messages by urging first home buyers to get into the market.

“It’s actually a good time, if you’re a first homebuyer, to buy the property that you’ve wanted. Interest rates are low and they’re going to stay low … I think it is a good time to buy.”

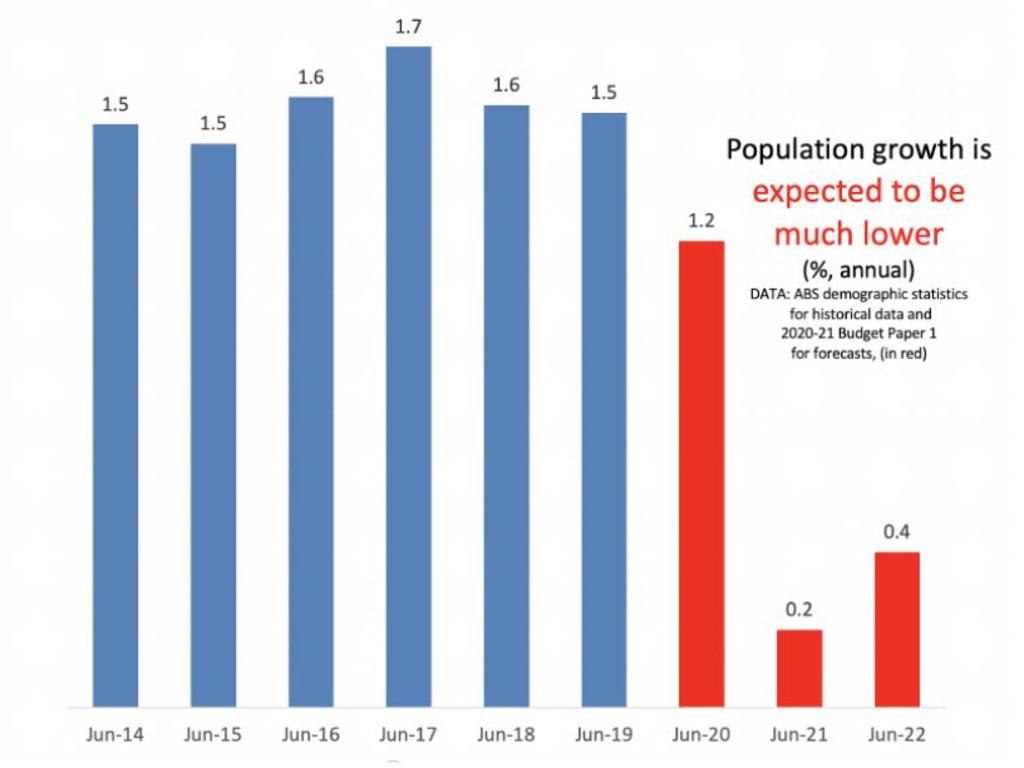

As the next graph shows, population growth is forecast to be lower until the end of June 2022, which is about 19 months away.

RELATED: Best $56 billion Australia ever wasted

The RBA is in a muddle. It doesn’t seem to know whether it expects housing to go up or down. It is focusing on the theory that low population growth will keep a lid on house prices. That would mean less willing buyers for homes. But theory and reality are only distant cousins.

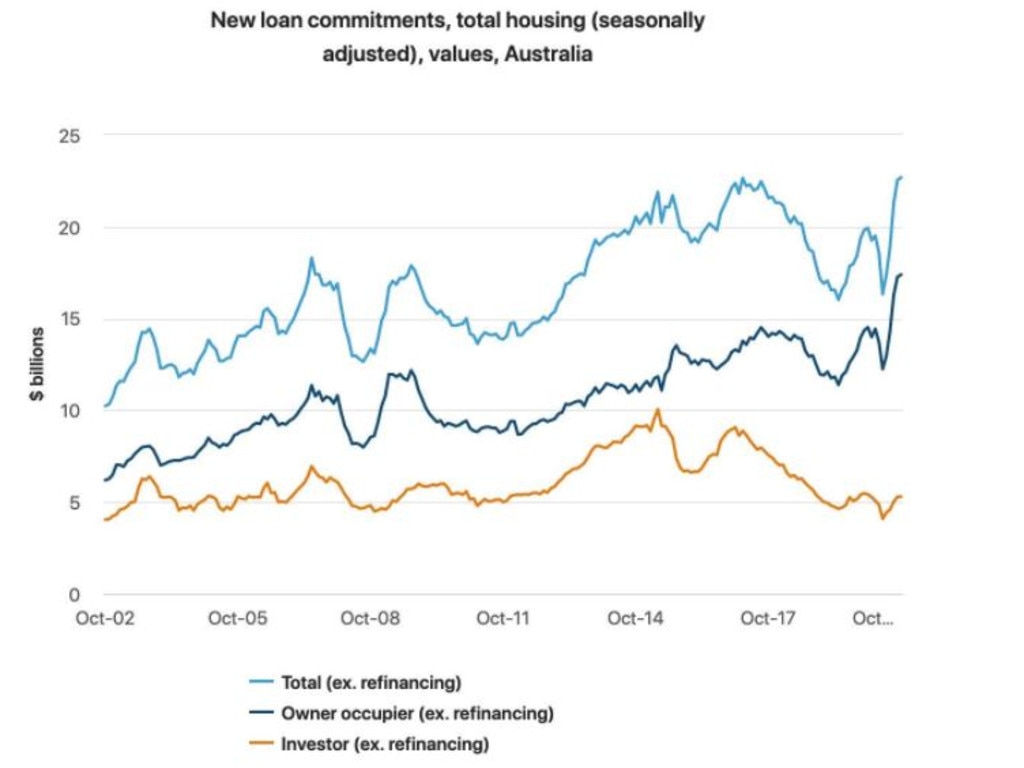

Meanwhile reality keeps kicking the Reserve Bank Governor in the groin. Australia is in a new house-buying frenzy. That’s the reality. The amount of money being borrowed to buy housing just hit a record high of over $22.5 billion in October.

RELATED: Aussie industries that are hiring big

Why? Interest rates matter most. And interest rates have just hit a record low. The latest lurch lower took official rates from 0.25 per cent down to 0.1 per cent. That’s translating into crazy-low mortgage rates. You can get a home loan with an interest rate under 2 per cent now. Which is almost free money. Home buyers are not shy about borrowing up big.

Every capital city in Australia saw house price growth in November, and regional areas grew twice as fast as the capitals, according to data from house price tracking company CoreLogic. We’re bouncing back very fast.

CoreLogic head of research Tim Lawless says the housing market is healing from its wounds remarkably fast.

“If housing values continue to rise at the current pace we could see a recovery from the COVID downturn as early as January or February next year.”

The amazing thing is the borrowing is all for owner-occupier housing. Investors are not back in the market, as you can see in the above graph. Rents are down, making investor housing look like a bad option. However, if investors come rushing back, tempted by rising prices, the market could hit even more spectacular highs. Million dollar homes turning into two million dollar homes, and so forth.

Does this make sense? the economy is not great. Unemployment is up. It will take years for joblessness to reduce to the levels of early 2020. Which were not very good. It doesn’t really feel safe for Australian house prices to be even higher, and debt loads to be heavier while the economy is weakened.

This is the big problem with using the RBA to accelerate the economy. When it cuts interest rates it is supposed to rev up businesses. Businesses are meant to borrow to build more shops and factories, buy more vans, hire more people etc. Once again, this is the theory. The reality is households do most of the borrowing and they don’t hire people. They just bid up the prices of existing assets.

TIMING IS EVERYTHING

So the RBA seems to hope that even though it has cut interest rates back to the bone, low population growth will keep house prices from going bonkers. Let’s assume for a second they will be right. Maybe during 2021 we will all realise there are actually more houses to go around than we need and house prices will moderate, despite the super-low interest rates.

There is still a timing problem. The RBA has promised super-low interest rates for three years. Official population growth forecasts show low growth but they only go out until 2021-22. That leaves a risky period for housing where interest rates will be at record lows and population growth might bounce back to record highs.

And progress on the vaccine has been very promising since those forecasts were published. If a vaccine arrives in nine months time, there is a chance our foreign students, migrants and tourists all come flooding back. The government will probably welcome back loads of people on temporary visas to try to give the economy a nudge along. That could mean a couple of years of house price boom.

The property price implications of high population growth and low rates are obvious. And frightening for anyone who doesn’t yet own a house. The RBA needs to think much more carefully about its impact on housing.

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy. He is the author of the book Incentivology.