A tale of two Aldis: Divided in two, the German supermarket is still able to rule the aisles

A FEW kilometres apart lies an invisible border. Known as the ‘Aldi equator’, it cuts the famous brand into two entirely separate, yet very similar, parts.

A FEW kilometres west of the city of Essen, in Germany’s industrial heartlands, lies an invisible border.

It’s not a remnant of the Cold War, or a national boundary. There are no signs marking its existence. But it’s there and it affects millions of people every day.

Between Essen and the neighbouring town of Mulheim is what’s known locally as the “Aldi equator”.

It’s a line that snakes through the retailer’s home country, cutting the globally famous brand into two entirely separate, yet very similar, parts.

That there are not one, but two Aldis, is one of the company’s myriad quirks.

Aldi’s enormous success in persuading penny pinchers to part with their cash has spawned reclusive billionaires, fuelled family feuds, led to a cigarette induced falling out and even a kidnapping.

On Wednesday, Aldi Australia announced it was signing up to the Tax Transparency Code

and in September, the private held company will publish its first ever Australian annual report.

It will lift the lid on a notoriously secret family run retailer which is subject to far less scrutiny than its listed homegrown rivals, Coles and Woolworths.

It has now overtaken IGA to become Australia’s third largest grocer. But it began far more modestly.

Still open to this day, the first ever Aldi debuted in 1913 just to the east of the equator in Essen.

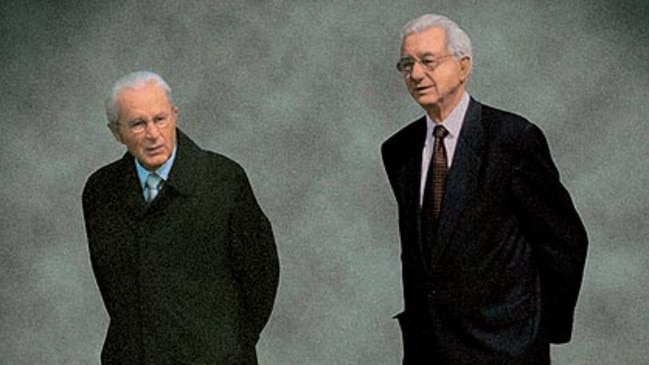

Brothers Theo and Karl Albrecht took over the store from their father in 1945. A decade later, there were 100 branches of what was known as Albrecht Diskont supermarket, a name that would eventually become the far snappier ‘Aldi’,

All was going swimmingly until 1960 when the brothers fell out reportedly over cigarettes. One wanted to sell them, the other didn’t. The solution? Split the company in two.

Theo ran the stores in northern Germany under the name Aldi Nord. Karl ran Aldi Sud in the country’s south. The Aldi equator divided the company.

The Aldi name is on all stores but there are subtle differences.

North of the line, Aldi stores were often more basic and sport blue and red signs. In the south, stores can be snazzier and have yellow and blue signs.

And the brothers didn’t just divvy up Germany, they divided up the world.

When you shop at an Aldi in Australia, UK or China you’re actually shopping at Aldi Sud. Snap up a special buy in France, Denmark or Poland and you’re a customer of Aldi Nord.

The only place where the two Albrecht’s coexist is the USA. Here Aldi Sud has naming rights. But the other side of the family, Aldi Nord, operates a separate, but not dissimilar, supermarket called Trader Joe’s.

Despite the split, Dieter Brandes, who was once a senior executive of Aldi Nord, said the two sides had always worked together.

“In foreign countries it was a case of ‘who started either first, goes first’, he told news.com.au.

Mr Brandes has written a book about his experience, Bare Essentials: The Aldi Way of Retailing. He says the secret to Aldi’s success has always been its simplicity. Supermarkets stocking 50 types of loo role might seem abundant but it turned off some shoppers.

“In many years, up to 80 per cent of Germans were almost regular customers of Aldi. Aldi became incredibly successful because of what I call the Aldi system.”

This included have a clear strategy. “Find a convincing concept and stick to it,” said Mr Brandes who believes in “radical simplification” and relying less on computers and consultants and more on staff.

It was a profitable formula but it brought the Albrecht’s unwanted attention.

In 1971, Theo was kidnapped. He was held hostage for 17 days, hidden in a wardrobe in Dusseldorf. The family is reported to have coughed up $3m to secure Theo’s release.

The Guardian reported Theo subsequently went to court to try and claim the ransom as a tax deductible business expense.

The kidnapping is said to be a chief reason the family became such recluses, rarely seen in public and never giving interviews.

Although Mr Brandes said that when it came to the day-to-day workings of Aldi he met Theo regularly as well as Karl from Aldi Sud. “I knew and met all the family members,” he said.

Both sides are the company are controlled by a complex series of trusts which benefit various corners of the Albrecht clan.

Neither Sud or Nord would comment for this article. But Aldi Australia told news.com.au they were, “proud to be part of Aldi Sud [that] has established itself as one of the most reputable retailers in the international market”.

A spokeswoman said that the Australian operations “are result of the lessons learnt from around the world” but the business was “decentralised”.

Many products in Australian stores were produced locally and while brands such as Choceur chocolate were sold globally, Mamia nappies and Expressi coffee pods were true blue.

Aldi Australia is not required to lodge accounts to the level of detail of a listed company.

However, in the year to 31 December 2014, the firm said its Australian operations racked up profits of $239 million on sales of $5.8 billion. Aldi said they paid the ATO $72 million in tax, an actual rate of 30 per cent.

Theo died in 2010, Karl in 2014, both billionaires many times over.

However, the usually quiet world of the Albrecht’s is increasingly coming to the fore.

The Aldi Nord baton was passed by Theo onto a clutch of family members who have, at times, disagreed how the business should be run.

Last year, Bloomberg reported that Theo’s eldest son, Theo Jr., had publicly attacked his widowed sister-in-law Babette criticising her purchases ranging from art to vintage cars. There were also disagreements over Babette’s plans to speedily spruce up stores.

“It’s totally natural that the younger generation would react against the excessive thriftiness,” Eberhard Fedtke, a former Aldi Nord manager told Bloomberg. “The parsimony was so extreme, it was unsustainable.”

Family wrangles aside, Aldi’s expansion seems far from over. It has recently pushed into South Australia and Western Australia and there are still several countries, like New Zealand and Canada, that are ripe for Aldi’s plucking.

Mr Brandes told news.com.au he only knew of one country Aldi had pulled out of and that was Sud’s withdrawal from Greece which he says was less to do with the company and “probably because of corruption issues,” and a unfavourable legal system.

But he strikes a note of caution. Aldi has prospered, he says, because of its simplicity of product and the lack of nimbleness among lumbering rivals.

“Nowadays, Aldi has become more and more a traditional retailer and lost some of their corporate culture.

“Their current success mainly depend on their huge strength, but also the weaknesses of many traditional retailers.”

There’s a chance that on that quiet backstreet in a suburb of Essen a thoroughly modern competitor is gearing up to give Aldi a run for its money.