After five years of trying, Trader Joe’s — a company related to Aldi — has finally succeeded in shutting down an imitation supermarket

A MAN who spent more than $1.7m setting up a fake supermarket has finally been forced to shut down operations.

A MAN who likened himself to a drug dealer, selling products sold by an Aldi “owned” company, to customers desperate for a fix of their favourite own label brands, has admitted defeat in a David vs. Goliath battle with the German giant.

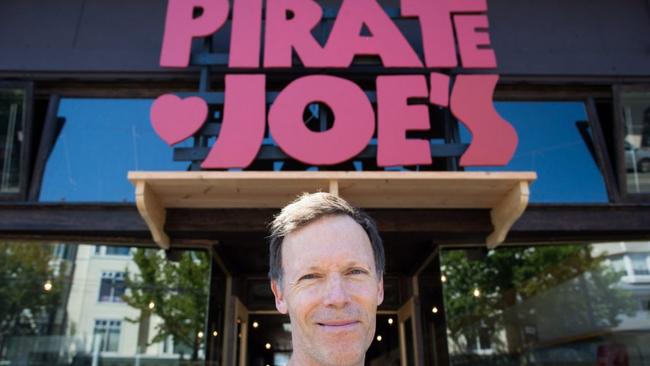

Mike Hallatt’s imitation supermarket finally shut down last week.

“It’s been a long time coming,” he said as the closing date for the store neared. “The prospect of going to trial against a major corporation when you’re one guy — you get lots of opinions from lawyers telling you: ‘Run.’”

Despite having no stores in Canada, a US company owned by the family behind Aldi, has never been happy with Mr Hallatt’s efforts to sell its goods out of Vancouver. But the Canadian has maintained that his business, which shipped products across the border, was all above board and should have been allowed to survive.

“This is completely legal,” he told the BBC last year. “No doubt [efforts to shut me down] is a question of brand control.”

Mr Hallatt opened his store called Pirate Joe’s in Vancouver in 2012. If the name seems unfamiliar that’s because Aldi’s ownership structure is complex. There are actually two different German companies called Aldi. One, Aldi Sud, runs Aldi branded stores in parts of Europe, the USA and Australia. The other, called Aldi Nord, owns Aldi branded stores in other countries and is closely related to Trader Joe’s.

Despite multiple requests, secretive Trader Joe’s refused to disclose to news.com.au just how close that relationship was but would not deny they had common ownership with Aldi Nord.

Indeed, Germany’s Handlesblatt has stated Aldi Nord “owns” Trader Joe’s, as has the US’ Bloomberg.

Trader Joe’s sells more organic and fancier fare than an Australian Aldi; things like Chocolate Dilemma Cheesecake and Quinoa Cowboy veggie burgers. But just like your average Aldi, the vast majority of the brands on sale are private label and unique to the store.

Vancouverites who wanted to shop at Trader Joe’s had to make the 90-minute trip south to Washington state or go without.

Mr Hallatt had a solution: he would do the legwork for them, stock up with as many products as possible from the nearest US Trader Joe’s and then sell it from a store in Vancouver.

“I’m kind of like a drug dealer. I’ve got you hooked with the vanilla meringues in France and now you have to get cases of them. But you don’t know about the triple ginger snaps” he told the BBC.

To him it seemed like a win-win situation. Mr Hallatt estimates he spent US$1.3m ($1.7m) on buying Trader Joe’s products at full price and then transporting them north for eager customers. And he made a healthy profit along the way.

“It’s really just a response to market. Trader Joe’s isn’t in Canada and have no plans to be here.

“I buy the stuff up. I own it, I get to do with it what it whatever I want to and I just happen to want to sell it to my friends,” he told US National Public Radio.

That wasn’t the way his erstwhile supplier saw it.

Just a year after Mr Hallatt set up his Pirate Joe’s supermarket, Trader Joe’s came calling demanding he shut up shop. Among other quibbles, they said the Pirate Joe’s brand in Canada was hurting the original brand in the US.

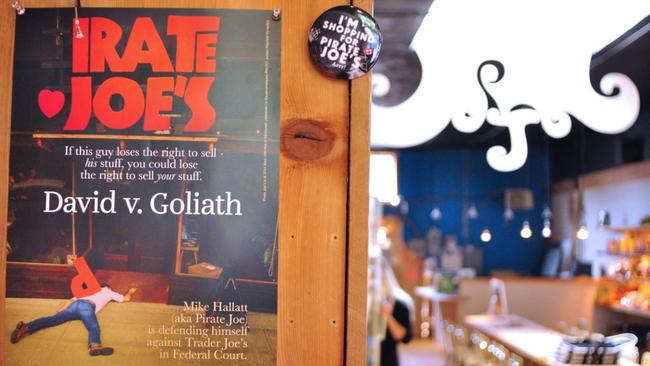

Mr Hallatt seems to have revelled in the battle between the global Behemoth and the plucky local grocer.

“Every time Trader Joe’s sues us we take the ‘P’ from our name down and it becomes ‘Irate Joe’s’,” he said in 2016. It certainly helped to bring more attention to his store.

Mr Hallatt scored some legal goals and initially his company couldn’t be closed down through the courts.

So Trader Joe’s tried other means. He was banned him from all their stores. He was kicked out on multiple occasions. But the canny Canadian had other ideas. He created an app with his shopping list on so he wouldn’t look suspicious clutching a huge piece of paper wandering the aisles.

He even went in disguise. Some days he would emerge from his battered white van sporting a moustache or a wig; one time he did the shop in drag.

When that didn’t work he hired a battalion of secret shoppers who would scour Trader Joe’s to his requirements. They would exchange the booty and then he would hotfoot it across the 49th parallel.

“Business hates uncertainty. When you’re sued by your supplier that’s like weaponised uncertainty. Basically your supplier hates your guts,” he told The Guardian.

The stress of having an $80 billion retail giant on his back did get to him and he thought of closing years ago.

“Then people would come up to me and thank me for doing it. That was the curse; we had so many people who loved what we do but it was devilishly hard to do.”

Trader Joe’s hit back in the courts and managed to overturn the original ruling. It was the final cheesy straw.

Mr Hallatt decided it was too much of a mission to have an Aldi-owned company against him. A legal battle would be long and costly. He came to an agreement with Aldi Nord’s Trader Joe’s unit to shut down. Trader Joe’s refused to comment to news.com.au about the campaign against pirate Joe’s.

Last Wednesday, Pirate Joe’s posted to Facebook that it would close forever that evening.

“We are sad that it had to come to this, but hey, at least we had some fun while we were at it right?!,” read the post.

His loyal shoppers were aghast. Queues formed. It was past midnight before he rang up the last sale — some pancake mix and chocolate biscuits.

In the battle of Trader Joe’s vs. Pirate Joe’s, the former has — finally — prevailed.

But by Friday morning, Canadians going cold turkey were channelling their wrath towards Aldi.

“Hey Trader Joe’s, aka Aldi,” said one former shopper on social media.

“As is customary, after you shut down the competition, you’re supposed to announce you are building stores in every major city in Canada ... Hello?!”