Mounting calls for Lawyer X case decision review

Serious questions have been raised about whether Victoria’s top prosecutor’s decision not to lay charges against four police officers and a disgraced barrister was due to a conflict of interest.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Justice figures are demanding a review of the decision by Victoria’s top prosecutor not to pursue charges in the Lawyer X case amid revelations she once represented Simon Overland, the former police chief at the centre of the scandal.

Director of Public Prosecutions Kerri Judd’s refusal to lay charges against at least five people including disgraced barrister Nicola Gobbo and four police officers has been called into question amid serious concerns of a conflict of interest.

Senior legal officials, including a former Vice President of the Victorian Bar Council, are calling for the briefs of evidence to be independently reassessed by interstate prosecutors as it has emerged Ms Judd personally represented Mr Overland in a 2010 inquest into the death of teen police shooting victim Tyler Cassidy.

Special Investigator Justice Geoffrey Nettle called for his office, the OSI, to be disbanded earlier this month, citing his anger that Ms Judd had repeatedly refused to support recommendations that several police officers should be charged.

OSI whistleblowers also claimed Mr Overland had “been let off the hook” amid claims he was the main target of investigators who believed he should have faced criminal charges.

Senior legal figures, including former senior prosecutors, believe Ms Judd should have recused herself from considering any OSI briefs given her client/barrister relationship with Mr Overland – who was central in the hiring of Gobbo to inform on her clients.

It is understood investigators at the OSI had no idea about Ms Judd’s previous history with Mr Overland.

“She should have removed herself entirely from this process,” one whistleblower said.

“She would have known we were working towards a brief on him, and the caning he got in the royal commission left no doubt he was a target of the OSI.”

The Herald Sun asked Ms Judd’s office if she should have recused herself from considering OSI briefs given the Lawyer X Royal Commission found Mr Overland was among several current and former police whose actions should be investigated as having potentially constituted “misconduct”.

Despite the fact Mr Overland had oversight of the police who the OSI recommended charges be laid against, Ms Judd’s office said: “The Director of Public Prosecutions had no conflict of interest in relation to the two briefs submitted for consideration.”

It is understood that none of the briefs submitted to the DPP for consideration recommended charges be laid against Mr Overland.

But OSI whistleblowers have also told the Herald Sun that investigators believed they had a “smoking gun” to implicate Mr Overland and their plan to send a brief of evidence on him to Ms Judd was scuppered when the OSI was shut down.

The Legal Services Board warns conflicts of interest can arise in cases where lawyers find themselves representing one client against a former client.

“The lawyer-client relationship does not completely end when a legal matter concludes,” LSB guidelines say.

“Lawyers and law practices have an obligation to avoid conflicts between the interests of their current clients and the interests of their former clients.”

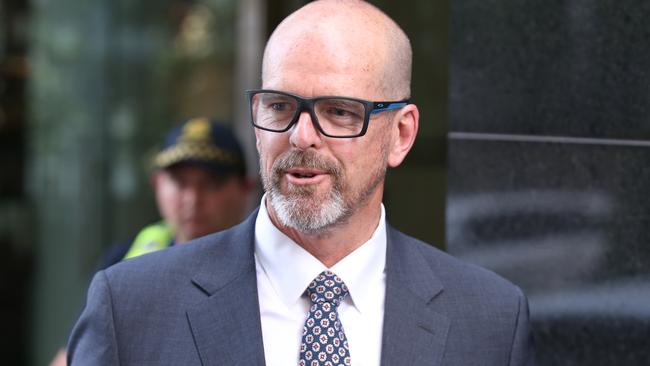

Senior barrister Darryl Burnett, a former Victorian Bar Council vice president, said OSI briefs should now be considered by an interstate prosecutor.

“In contentious legal matters where local high profile identities are involved it is not uncommon for the decision to prosecute potential criminal conduct to be delegated to an interstate DPP,” he said.

“The interstate DPP will likely have had no professional relationships with the identities, in fact they may have no prior knowledge of the identities at all.

“In the Lawyer X case the delegated interstate DPP could be presented with the extensive briefs of evidence prepared by Mr Nettle in which he recommends prosecutions.”

Ms Judd represented Mr Overland during a coronial inquest into the case of Tyler Cassidy – a 15-year-old boy who was shot dead by three police in a Northcote skate park in 2008.

Following a 34-day inquest, a coroner found at least one of the officers’ lives were in immediate danger from Tyler, who was armed with two knives and advancing on police.

Shadow Attorney-General Michael O’Brien said the rejected OSI briefs should now be subject to a second opinion.

“To avoid any perception of a conflict of interest, the DPP should ask an interstate counterpart to review Justice Nettle’s extensive brief of evidence and advise whether charges should be brought,” he said.

“Justice must not only be done, it must be seen to be done. That’s why it is vital that the DPP explains to Victorians how she manages any potential perception of a conflict of interest when it comes to the Lawyer X scandal.”

The Herald Sun also this month revealed claims Ms Judd had expressed doubt that OSI investigators would “get anywhere” just months after the body was established.

A Victorian Government spokesperson said prosecutorial decisions were a matter for the Office of Public Prosecutions.

“It is critical that it operates independently of Government and statutory bodies like the OSI.”

“The Government has full confidence in the DPP and the OPP’s capacity as an independent prosecutorial body,” the spokesperson said.

- Shannon Deery

Gobbo fed detectives clues about her clients

The client and his lawyer held hands.

She was crying, he was comforting her, in a scene which didn’t make much sense.

He had just been arrested at a drug lab near a primary school in Strathmore.

He was going away for a long time. He was considered the best drug cook in Melbourne, the preferred cook of the Mokbels, and he faced sentencing for other very serious drug charges.

So why was the client seeking to console the lawyer?

The lawyer was Nicola Gobbo. She provided more than advice for this client. The pair had spoken about the “what ifs” of a romantic relationship, in what she called “cock tease” approach to winning his trust.

She consulted his doctor about rehab on his behalf. Gobbo was his friend, confidante, secretary and occasional babysitter of his children.

He couldn’t know that she was also his nemesis, that the only reason that he was sitting here at all, puffing on smokes and contemplating a 30-year stretch, was because his “friend” had betrayed him.

Later, the drug cook told a royal commission about his discussion with his lawyer.

“She looked so distressed,” he said. “She was shaking her head from side to side saying: ‘No, I can’t fix this’.”

“I told her not to worry,” said the drug cook, who cannot be named.

“They know everything,” Gobbo replied.

Of course the police knew everything – because Gobbo had told them everything.

For months, Gobbo had reported the cook’s criminal pursuits to her handlers in the top-secret Source Development Unit of Victoria Police.

Gobbo had fed the detectives clues, leading to the drug lab arrests (which inspired a police cover story about how a detective and his daughter happened to be walking by the lab when the daughter heard tapping).

She told them how the cook had identified a number of unmarked police cars which were following him.

Not long before, she had “hosted” the cook’s 40th birthday party, where she won the dance contest, and had received the RSVPs so that she could reliably inform her police handlers which of Melbourne’s heaviest crims would be there.

But it’s what happened after the arrest which mainly led the Office of the Special Investigator to recommend the laying of criminal charges against some police officers.

Ex High Court judge Geoffrey Nettle, as the special investigator, believes that several of them should be prosecuted for perverting the course of justice.

IT WAS April, 2006, a few days before the nation would be captivated by the rescue of two miners trapped in a Beaconsfield mine in Tasmania.

Gobbo was told to ignore her police handlers when she arrived at the station. Much planning had preceded the drug cook’s arrest; Gobbo and police had even discussed the type of cigarettes that he should be offered.

The police needed the drug cook to roll on his Mokbel associates.

When he was first questioned, without Gobbo, he had predictably offered a no-comment interview to police.

Then Gobbo, who had been waiting at a nearby hotel in South Melbourne, got the call late in the afternoon.

The police knew the cook would ring his lawyer. And they also knew that his lawyer would tell them everything that he told her, nevermind the timeless protections of legal professional privilege.

Gobbo met with her client for about an hour. It was at this point that she cried and he fretted that his lawyer might be implicated (and endangered) by his arrest.

She explained that if he stayed silent he faced no possibility of seeing his children on the outside until they were middle-aged.

But there was a better option, as unpalatable as it sounded. He could give up his criminal friends.

Gobbo, a seasoned performer, thrived behind her projected sympathy.

The cook later said: “She told me I needed to make a deal – ‘Let me go speak with them and sort something out’.”

Pizza was shared in an oddly festive vibe in a boardroom on the 14th floor of the St Kilda Rd Police Complex.

The cook, Gobbo and a detective chatted privately for two hours, in what would become known as “the pitch”.

The cook was then interviewed again.

Hours earlier, he could not have fathomed rolling against the Mokbels. Gobbo had since convinced him otherwise. Over 456 questions, he talked and talked.

The cook’s information was the mother lode. In stings starting the next day, criminal after criminal, including Tony’s brother Milad Mokbel, would be arrested and charged.

The hapless cook was compelled to play along, to be “arrested” for show when the police suddenly descended on criminal meetings and drug exchanges.

In all, over 40 statements as a prosecution witness, the cook’s information would directly lead to 26 convictions.

“The general ethics of all this is f***ed,” Gobbo had told her handlers prior to the arrest.

A royal commission and the Office of the State Prosecutor would later concur (in more civilised terms), along with an ex-Supreme Court judge and a long queue of pre-eminent KCs.

Indeed, appeals against convictions multiplied when details of this specific deception were revealed.

One of the cook’s associates, Zlate Cvetanovski, was jailed for 11 years for his alleged role in the drug production, only to have his conviction overturned in 2020.

In its final report, the Gobbo royal commission did not “accept that there was no knowing impropriety on the part of any officer involved in these events”.

It concluded that a court, rather than Victoria Police, should have determined whether Gobbo’s hidden role in the investigation and prosecution of the cook’s associates be revealed to the defendants.

It found that the “conduct of some officers fell well short of an acceptable standard”.

Yet current DPP Kerri Judd concluded that there was nothing – at least in a prosecutorial sense – to see here.

Increasingly strident correspondence between Nettle – one of Australia’s most respected legal minds – and Judd in recent months depicts deeply conflicting opinions of the evidence for prosecutions.

Nettle argued that Gobbo had agreed to plead guilty to perverting the course of justice, and that cases against police officers in the events described above could be made without witness testimonies.

But as it stands there will be no legal reckoning for either Gobbo or her police handlers, despite the almost universal legal condemnation for such unprecedented and unethical collusion.

Like so many elements of the bigger Gobbo story, it doesn’t seem to make much sense.

- Patrick Carlyon