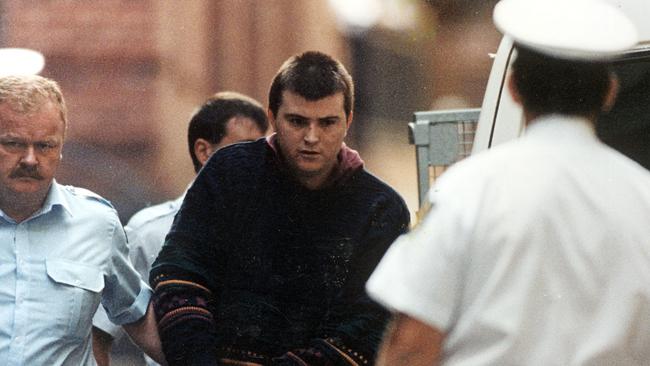

How Frankston serial killer Paul Denyer will apply for parole

Paul Denyer’s bid to be released has put a spotlight on Victoria’s parole process — so how do violent criminals seek freedom and what are their chances of success?

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The road to release for jailed serial killer Paul Denyer cannot be decided in a single meeting of the Adult Parole Board.

Denyer’s crimes, the murder of three women in 1993, are at the highest end of offending.

He was initially sentenced to life in jail with no prospect of release, but appealed and got a 30-year minimum term.

It will take months for the board to make a decision on this case.

And it would be stunning if Denyer’s parole application was granted.

Denyer is categorised, quite rightly, as a serious violent offender.

These inmates are put through a “two tier” system to ascertain suitable applicants for parole.

The two tier system also applies to sex offenders.

Although Denyer is eligible for parole, it doesn’t mean he is going to get it.

The Herald Sun understands Denyer’s application will be reviewed in the near future as part of the “tier one” process, possibly as early as next week.

Denyer’s application, and the findings of the first review, will then come before the board’s full-time members as part of “tier two”, a process put in place to ensure higher scrutiny of our most serious offenders eligible for parole.

The board’s chairman, His Honour David Fanning, will then make the ultimate decision.

Given the heinous crimes Denyer has committed, his lack of remorse and failure to attempt to rehabilitate, the 50-year-old does not make for a compelling case for parole.

The board will not only review Denyer’s file, but delve into issues such as whether he has completed any educational courses, (which he has not) and assess psychological reports.

Critically, the most important consideration for the board will be whether Denyer remains a risk to the community.

Public safety is its key concern.

Determining parole applications is an unenviable task and members of the board do so with the knowledge there is always a risk the parolee will reoffend.

A spotlight was shone on the board in the wake of ABC staffer Jill Meagher’s murder by serial rapist Adrian Bayley, who was on parole in 2012 when he murdered her.

Bayley had already breached his parole conditions and should have been in jail at the time.

A review found the board was underfunded and was struggling to handle its workload.

Its work, back then, was predominantly done with physical files.

As a result of the review, changes were made including a more stringent parole system.

In effect, parole became harder for inmates to get.

In its 2021-2022 annual report, APB data revealed it decided 1036 parole applications, granting 673 (65 per cent) and denying 363 (35 per cent).

Most of those inmates would not be in the serious violent offender category.

Of all prisoners granted parole, the board stated 81 per cent got through it successfully.

It reported that five inmates granted parole were convicted of committing serious offences in that period.

But the board does more than just consider parole applications.

In its report, the board stated it considered 7531 matters across 270 hearing days.

That’s an average of 28 matters considered per hearing day.

Denyer is now one of them.

His history, including behaviour in prison, drug testing results and all intelligence held by police, Corrections Victoria and the justice department will be tabled.

There’s also the issue that Denyer is a suspect in the murder of missing woman Sarah MacDiarmid in July, 1990.

Investigators are keen to solve Ms MacDiarmid’ s murder and have received new information about it.

If Denyer is denied parole, which is on the cards, he can keep reapplying.

And, for many years, the board can reject his bids for freedom.