‘Dangerous business’: Undercover cop’s ‘Mr Big’ tactic sparks controversy

A convicted killer was jailed after revealing to his friend the vicious way he lethally laced orange juice to murder his lover’s husband. Little did he know he was spilling to a cop.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A controversial police tactic to insert an undercover officer into a murder investigation has again been questioned over its ethics and accuracy.

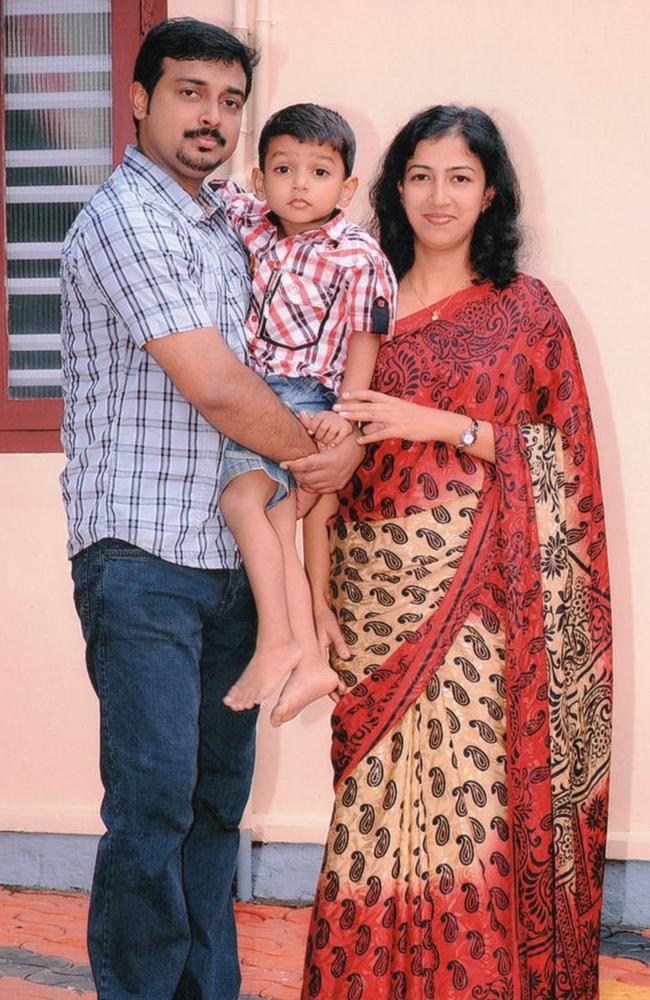

Convicted killer Arun Kamalasanan detailed his subtle yet vicious murder plot to an undercover cop posing as an associate in an admission that would help jail the man for decades.

The covert policeman was told how the killer laced his victim’s orange juice with cyanide before feeding it to him while he slept in a murderous plot against his lover’s husband.

Kamalasanan, who is serving 24 years behind bars, was later found guilty of murdering Epping man Sam Abraham at his home in October 2015.

Kamalasanan’s admission to his fake friend, the undercover officer, would assist in convicting him and his lover, Sofia Sam, over the high-profile love-triangle killing.

The tactic of deploying the undercover cop in a murder investigation, known as the ‘Mr Big’ method, was central in convicting another killer who committed an “atrocious” homicide.

Those detectives, investigating the murder of Melbourne mother Mary Lou Cook, knew their suspect enjoyed a drink at his local pub each Friday night.

They sent an undercover cop to pull up a stool next to factory worker Glen Weaven, hoping the pair would get along.

That undercover officer would return to the same suburban pub for weeks on end, building a friendly relationship with the man they believed stabbed Ms Cook before burning her body in 2008.

Weaven had been off work nursing a broken arm he sustained from falling over a pallet at a factory weeks earlier.

His funds were beginning to dry up.

The undercover police officer, posing as a member of a criminal network, offered Weaven an unofficial job running cash from various sites between Canberra and Adelaide.

It was an easy way for a bloke with an abundance of spare time to make a few hundred dollars each week.

Weaven was, after weeks of earning a dodgy wage, pressured to confess to the fake syndicate’s boss of his real criminal history.

He would later admit his crime to the boss, who was “Mr Big”, describing his involvement in the 2008 murder and disclosing where the kitchen knife had been discarded.

“They took him to get the knife and it was all over then,” one source with close knowledge of the investigation said.

The tactic has been used in a number of successful prosecutions across the country, including that of Brett Cowan, who murdered Queensland boy Daniel Morcombe.

Cowan was, when he was one of the main suspects, recruited by a “gang” who would get him to assist in a series of staged criminal acts, including a raid on a warehouse to steal packs of smokes.

The suspect was reportedly also involved in the purchase of illegal firearms, among other jobs, to earn some cash.

He then met his “Mr Big” and would later admit to his crime — a revelation that would play a major role in his conviction.

Ethics of ‘Mr Big’ questioned

But it begs the question; should authorities continue using the controversial tactic of deploying a “Mr Big” in their investigations?

The ethics surrounding the covert operation have been questioned, doubted and debated for years.

The tactic delivered lengthy convictions to several key murder suspects, particularly in cold cases stretching decades.

But asking undercover cops to pose as criminals has always raised some eyebrows.

The legitimacy of the evidence gathered in the Mr Big operations has often been questioned, as has preying on suspects who battle financial problems and addiction.

Greg Barnes SC, one of the country’s most high profile barristers, called out the “hypocrisy” in the underground policing method.

“No one should be induced to commit a criminal offence, or to encourage another person to commit a criminal offence, that should be our starting point,” he told the Sunday Herald Sun.

“On one hand you’ve got this incessant war on drugs, on the other hand you’ve got police operations which allow drug trafficking to run, because they want to go after particular targets.

“You’re asking them to engage in dangerous business.”

Mr Barnes, from the Australian Lawyers Alliance, said courts needed to tighten the parameters surrounding the practice to keep both parties in check.

“There needs to be quite strict guidelines around the way in which it’s done and the use of evidence,” he added.

“Courts ought to be very vigilant ensuring those restrictions are respected.

“And if you allow it, there are often issues with the reliability of the evidence.”

But former leading homicide squad investigator Charlie Bezzina said the tactic assisted in securing several convictions – and that was the main goal for police.

“It is one of the most valuable tools that Victoria Police investigators have got,” he said.

“I say that because the avenues of gaining evidence are becoming a lot more stricter.

“It’s still getting to the truth of the matter and that’s one of main drivers for police.

“The fairness and frankness to the accused still remains, but it’s an ability for investigators to gain evidence that would never be gained possibly by no other process.”

Lisanne Adam, a lead researcher and RMIT lecturer, said the ethics and success of the “Mr Big” operation created a “conundrum”.

“It’s very controversial, it’s misleading and deceptive,” she said.

“We know of (a suspect) who was living out of their car, with a drug addiction, and then being lured into this, and those cases can be problematic.

“Are we going for the protection of people or are we going for guilty people walking free if we don’t use this method? It’s really a conundrum.”