Andrew Rule: No closer to the truth on Julie Ann Garciacelay’s murder mystery

It’s all but certain one of two violent men who accompanied a crime writer to Julie Garciacelay’s North Melbourne flat murdered her. But 48 years on, we’re no closer to the truth.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The odds against meeting someone with the same three initials in a small workplace are thousands to one. The odds against that person being with you the night you get murdered are astronomical.

That’s what happened to Julie Ann Garciacelay, whose fleeting acquaintance with John Alexander Grant in the winter of 1975 ended with her murder. Not, it must be stressed, through any fault of Grant’s — except for the company he kept as a crime reporter.

It’s all but certain that one of two violent men that Grant accompanied to Julie Garciacelay’s North Melbourne flat on the night of July 1 murdered her. But her body was never found and no one has ever been charged.

Seven years ago this week, detectives delivered a long overdue brief to the coroner containing the few threadbare facts surrounding Julie’s disappearance on that long-ago night.

Almost two years later, a coroner delivered the only logical finding: that Garciacelay had been murdered, her body disposed of at a place and by a method unknown.

But who did it?

Was it one of the three men, or two of them?

Or was it the scenario that Grant and the other pair put to police that week and never retracted or notably altered: that Julie had gone to make a phone call from a nearby phone booth and never returned? This conveniently implied that someone had abducted her — or that she had run away.

The phone booth story is questionable though not impossible. It was enough to frustrate detectives who could not shake the three men’s stories then or later. Telephone records indicated no call was made from that booth at the time, but it left a sliver of doubt.

Julie Ann Garciacelay was from California. She’d been in Australia only eight months and was a week from her 20th birthday the night she vanished.

She had come to join her older sister Gail, who was working at the Melbourne telephone exchange. The sisters shared the Canning St flat where Julie was killed but on the night in question Gail had stayed elsewhere, returning the next day to find the flat blood-spattered and empty.

Julie worked in the library at Southdown Press in Latrobe St, in those days the Melbourne office of The Australian and Truth newspapers. There she would have seen the young man who shared her initials, John Grant, a Truth crime reporter. Not that they were friends.

Grant, known as “Grunter”, was one of a raffish crew led by “the fighting journo” Jack Darmody, a Runyonesque character who boxed nearly as well as he wrote for the racy tabloid renowned for form guides, saucy pictures, risque stories, tawdry scandals — and sometimes remarkable scoops.

Truth crime writers back then knocked about with knockabouts — gunmen and conmen, hookers and thieves, boxers, bouncers and bikies. John Grant learned the crime beat from the bottom up.

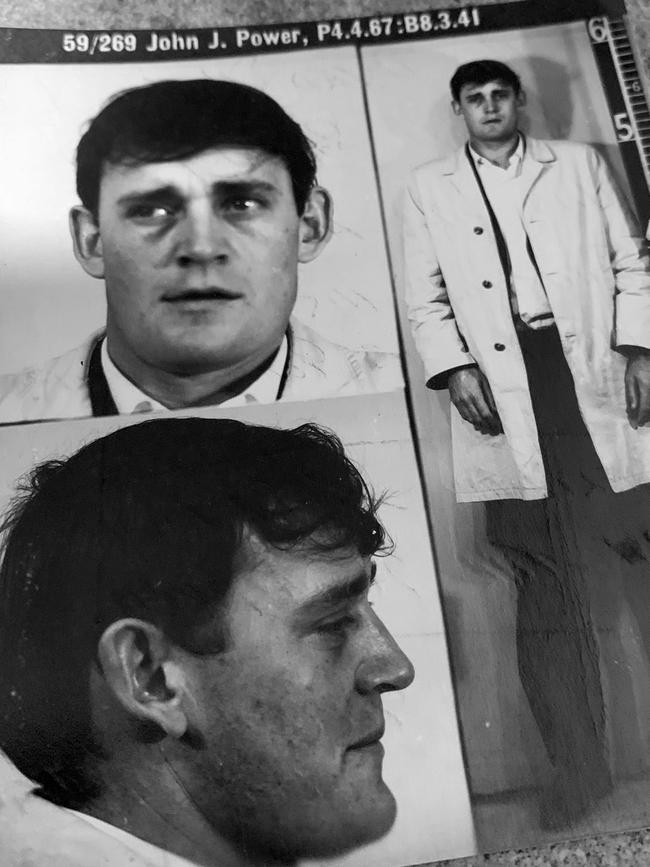

Among his contacts were the violent John Joseph Power and hard man Rhys “Tommy” Collins, an ex-welterweight who’d fought in Australia’s first televised boxing match in 1957.

Grant was trusted by serious crooks, certain police and lawyers and also by his workmates, from editor Mark Day, news editor Adrian Tame, renowned court reporters David Dawson and Steve Butcher and all-rounder Daryl Timms.

Grant came to work one day and mentioned he’d watched the film “Bonnie and Clyde” the night before with “Jockey” Smith, one of Australia’s most wanted fugitives.

Tame trusted Grant so much he and his wife got him to babysit their young daughters. Tame recalls that when he and Grant went to the Hells Angels clubhouse in Fairfield (to discuss a documentary), the notoriously aggressive bikies treated Grant as an equal.

John Power and “Tommy” Collins had been involved in providing information, if not evidence, to push the anti-police line at the Beach inquiry into police corruption, which sat through most of 1975 and 1976.

As sources for Truth reporters, Power and Collins got to hang around the editorial library to look up crime news clippings.

Collins, deceptively charming compared with the menacing Power, had used the opportunity to get to know library staff. He had discussed with the American girl an idea of starting a soul food restaurant.

Power, who’d beaten a charge of killing a woman just three years earlier, was known to Truth staff. When Grant saw Power and Collins in the office on the afternoon of July 1, he took them to their usual pub, a short walk away. After a few beers Grant bought a dozen cans and joined Power and Collins in Power’s car to “kick on.”

As Grant later told it, Collins directed Power to the Canning St flat, which suggests he had been there before or had memorised the address. (This was confirmed by Collins, who told police he’d met up with Julie Garciacelay the day before.)

Grant later claimed to have been surprised to discover, on arrival, that their host was the American girl he’d seen in the office library.

In the statement Grant made the day after Julie was declared missing, he stated he and Power had left the flat to buy pizzas in Racecourse Rd, Flemington.

When Grant and Power returned to the flat with the pizzas (Grant told police), Power had commented “Tommy might try the sour”. This was short for “sour grape”, rhyming slang for rape.

Grant told police he and Power listened at the door and hearing “nothing to support Power’s suggestion” they knocked on the door and were let in.

There, according to Grant’s statement, they ate the pizza and drank more beer. Then, he stated, “the girl” said she was going to make a phone call — which meant going to a phone box in the street. He said she’d left the flat, pen in hand, and that the three men waited, eating pizza, but that she didn’t return.

That story could be correct. It was true Julie’s sister Gail had asked her to call in “sick” for her to dodge work next day, leaving the number and coins to make the call. It’s possible she used the phone call as a pretext to leave the flat and deliberately stayed out until the three men left.

Grant stated that Power dropped Collins at home (at what he thought was Rosanna) then drove back to the city to drop Grant at the Truth office in Latrobe St. There, he claimed, he went in and called Tame for permission for a cab chit to get home.

It didn’t occur to police to check the cab-docket book at the Truth office to verify Grant’s movements and timeline but no attempt was made to do that until 2003, some 28 years too late.

Grant’s version of events is that when he arrived at work the next day he found Darmody and others worried because Julie Garciacelay was missing — and blood and underclothes had been found in her flat.

Concerned he’d be tangled in a homicide investigation, Grant took refuge at Darmody’s house but was subsequently told that the police knew about Power and Collins being at the flat and so he should co-operate with investigators.

No street smart person would want to implicate such dangerous men in a crime. Grant’s unsigned statement basically corroborated Collins and Power.

There is nothing to say Grant knew any more than he’d told police. But he must have had private suspicions about one or both of the others — especially of the dangerous Power, last seen driving up Latrobe St, a few blocks from North Melbourne, late at night.

When another generation of police came knocking in 2003, trying to solve what had become the coldest of cold cases, Grant gave a no comment interview. He has refused to speak of the case ever since.

Power gave rambling non-answers in 2003 and subsequently got away on medical grounds with refusing to be interviewed before his death in 2012.

As for “Tommy” Collins, he died relatively young in 1998. His wife inserted a death notice which read, in part: “Tears pour from my eyes when I remember the agony you suffered.”

Was this an oblique reference to Collins living with a guilty conscience and suspicion?

If Collins wasn’t haunted, Grant was. His former editor Mark Day is one of several who recall Grant repeatedly, tearfully and drunkenly swearing his innocence, weeping about the terrible rumour and innuendo that linked him to Easey St and the Garciacelay disappearance. Day believes he was genuinely distressed, unless he was a wonderful actor even when drunk.

It is a mystery that author Helen Thomas has spent months trying to unravel. Apart from tracing people, she has obtained the few documents attached to the case, including statements made by Grant, Power and Collins in 1975.

Thomas, who was a cub reporter in 1975, became fascinated in the case decades later while researching her definitive account of the Easey St murders, which happened in Collingwood 18 months after Julie Garciacelay’s disappearance.

The more that Thomas studied the savage killing of Sue Bartlett and Suzanne Armstrong, the more she wondered if Garciacelay’s murder might be a prequel to that terrible crime, marked by a tragic coincidence that has dogged John Grant most of his adult life.

The coincidence is that Grant, one of the last to see Julie Garciacelay alive, was by chance staying the night in the terrace house next to the one where Sue Bartlett and Suzanne Armstrong were murdered at 147 Easey St on the night of January 10, 1977.

It was natural that the police would seize on this. The then head of the homicide squad, Noel Jubb, once assured this reporter that detectives put Grant through a lengthy interrogation that came up empty.

There was nothing to connect Grant to the stabbing frenzy that happened on the other side of a wall just metres from where he’d spent the night after playing pool with his hosts, newspaper employee Illona Stevens and her housemate Janet Powell.

It was Stevens, a dog lover, who discovered her murdered neighbours’ bodies (and Armstong’s starving toddler Greg in his cot) after returning their young dog, which she’d found wandering in the street.

Stevens has never had any suspicion of Grant and, apparently, neither has anyone else who knew him well.

Thomas is now trying to unravel a case that was, like the Easey St murders, poorly handled by 1970s police. She has found witnesses that police never spoke to. And she has traced Julie’s extremely old mother in California, telling her what the police and the coroner had not: that, in 2018, an inquest had finally declared her girl was murdered.

The old woman, in her 90s, told Thomas that Julie’s sister Gail had never recovered from grief and survivor’s guilt. She died long ago, wishing she’d never asked her little sister to join her in Australia.

Footnote: John Joseph Power would subsequently be convicted of stabbing another young woman, and served some 30 years in prison for that and other crimes.