Andrew Rule: How Larry Blair avoided following his father into life of fear and loathing

A mum and son wake to muffled voices in the corridor outside the hotel room and know death could be moments away. Welcome to the terrifying childhood of Larry Blair, who somehow found an escape hatch from life in a criminal family.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Nightmares are made of this.

The plane is just about to taxi onto the runway when Larry Blair’s mother spots a member of the “Toecutter” gang sitting behind them. It’s Billy Maloney, one of the men who tortured and murdered her husband.

Patricia Blair is as decisive and intuitive as she is beautiful. Instead of freezing with terror, she acts.

She hurries to the cockpit and persuades the captain to abort take-off and to call police to the tarmac so she and her boy can be escorted off.

Escorted to safety, you’d think. But not so. This is 1970 Sydney, one of the most corrupt cities in the western world.

Police take the anxious mother and the 11-year-old to a cheap hotel. They are lying in bed, wide awake, after midnight, when they hear a trolley squeaking along the corridor and muffled voices as it stops at each room.

Patricia’s survival instincts flare for the second time in 12 hours. It’s too late for staff to be using a trolley. It must be bent cops or their toecutter mates hunting for them.

She whispers to Larry and pushes him out the window to climb down a precarious downpipe. She follows. They get over a side fence and hide in time to hear a crash from the room: it’s the intruders breaking the door down a minute too late.

At dawn, they sneak into a passing taxi and head to a bus station. By dark they are in Melbourne. For what seems like months, they hide in a suburban house in Frankston with “Uncle Alf and Auntie Joan.”

The kid goes to school using a false name. His mother mostly stays in the house. “Uncle Alf” builds a tall fence and puts bells on it to give them warning of intruders.

Frankston proves a safe place to hide but Larry can’t help imagining the red-haired Billy Maloney is following him. Later, when the runaways can’t impose on their hosts any more, they risk returning to Sydney.

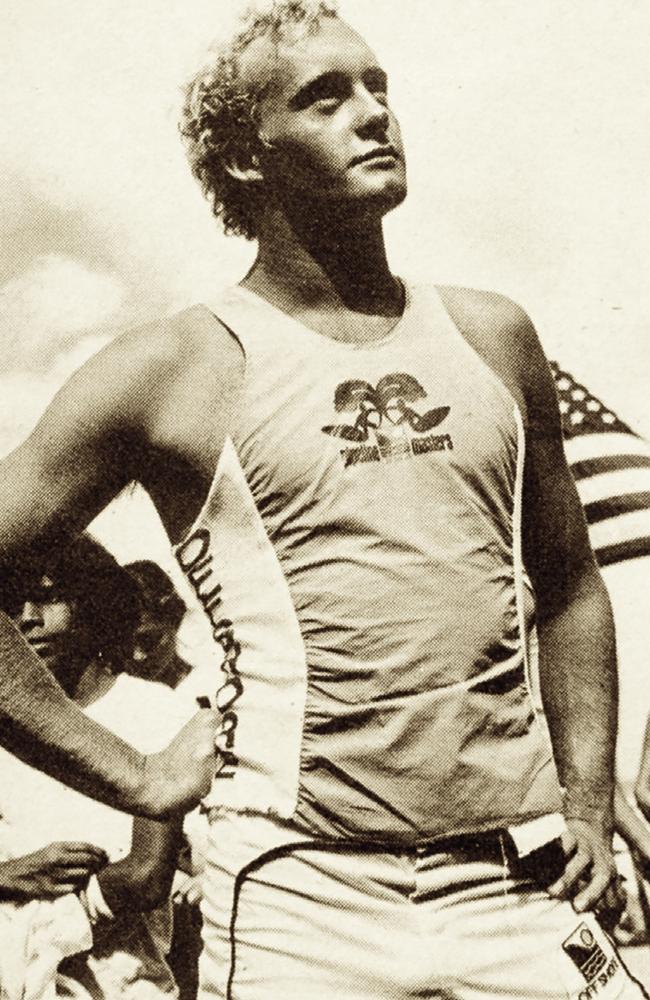

That’s the story of how young Larry Blair, future world surfing champion, became a fugitive with his mother, one of the slickest jewel thieves and confidence tricksters in the land.

Mother and son looked over their shoulders for years. Later, as a young man, Larry started wanting to find the man he blamed most for betraying and killing his father. At least three criminals had been involved in torturing Frank “Baldy” Blair, but the one Larry hated and feared most was Maloney.

The crew had always met at the Oceanic Hotel at Coogee. As a young boy, Larry would drop in there after school.

“Dad has a lot of pals, comrades and friends and I can’t always tell which dog belongs to which pack,” the now middle-aged man recalls.

“Out of all Dad’s crew, Billy Maloney, the affable Irish sheep, is the most interested in me … Billy laughs and goes along with whatever Dad says, and usually gives me money with a smile. It’s just that his smiles never quite fit his face.”

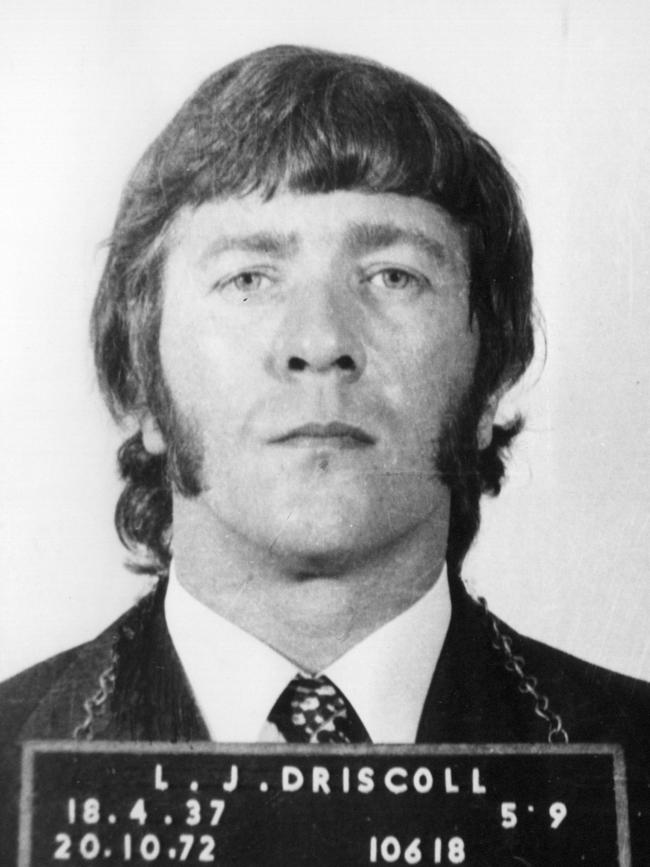

The other “mate” is “Jimmy the Pom” Driscoll, who despite the name is a deadly Irishman. Steve Nittes and a crook he simply calls “Fletcher” are ex-boxers who’d come from Melbourne with Blair and are apparently loyal to him.

Larry Blair (and his co-author Jeremy Goring) sums up the Oceanic Hotel gang this way: “Pals, friends, mates and comrades. There are so many of them in the entourage … who can know which face is thinking what?”

It sounds ominous and it is. Larry is in his mid-60s now but those faces still haunt him. His new memoir The Outside traces his spectacular surfing career but it is the intertwined story of fugitive mother and son that makes this rare insider snapshot of the 1970s Australian underworld so compelling.

The book is not a police brief or conventional journalism. It’s personal. Dates and places are wobbly and some names have been changed for good reasons and bad, but the truth of his story is in the sense of fear and loathing. It is a chilling insight into the effect of the criminal life on the families of criminals. Especially on children.

In the underworld, some kids are infected by what Mafiosi call “the life,” the gangster braggadocio and the fatal lure of “easy” money, as in fast money scored without hard work.

Other children born into criminal families are just damaged, full stop. This story told by the son of a robber who was tortured to death brings that harsh truth into focus.

Larry Blair would achieve legitimate fame, as opposed to his father’s fleeting notoriety, by winning World Masters’ surfing titles. But underneath the glory and glamour on the crest of the pro surfing wave (and his time as an actor), the son of the murdered robber and his beautiful jewel thief wife was deeply disturbed.

Larry never got to farewell his father at a funeral. All he could do, later, was talk to old crooks who suggested that the “womanising bully” he called Dad had his toes cut off and body parts burnt and that his body had been dissolved in acid and dumped under the extension of the Sydney airport runway.

Long before Larry Blair became a bigtime surfer and small-time actor, he was a terrified kid, thrown around like a pinball by his parents’ life on the dark side.

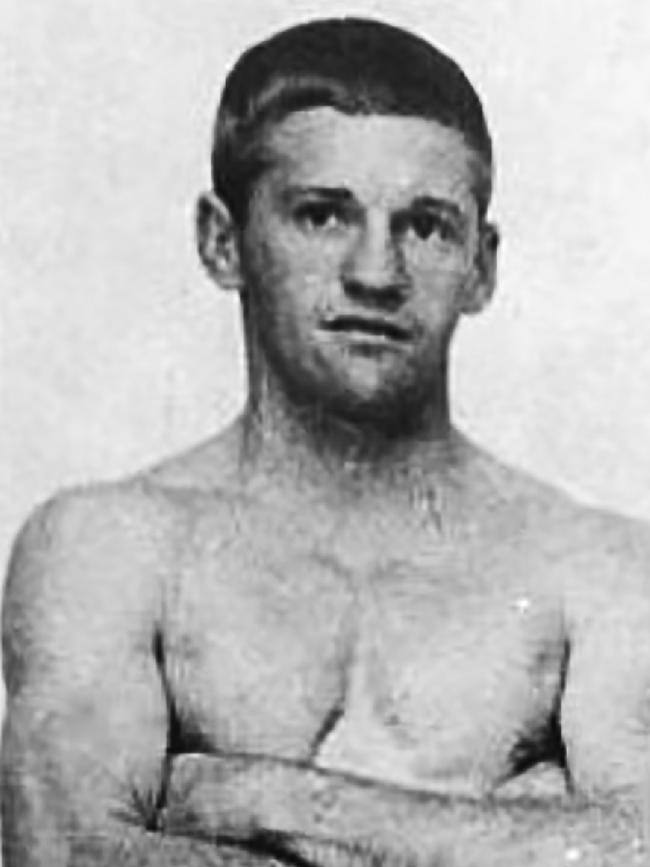

The man he called his father, Baldy Blair, was one of the brazen robbers who pulled off Australia’s first and biggest armoured car heists in 1970: the Mayne Nickless job in Sydney that netted $587,890.

An alert criminal “mastermind”, Les “Wooka” Woon, had information that on its regular run to the Reserve Bank, this particular van collected cash all over western Sydney. More importantly, the van’s three guards stopped at the same car park each day to eat their lunch.

To have a predictable routine was unwise but to step out of the van each day to dispose of their lunch wrappers was idiotic.

The guards were easy to rob. And the robbers made identification hard. They wore mirrored hats and sunglasses and long striped butcher’s aprons to confuse onlookers.

The take, in modern terms, was equivalent to $10m. About half went to “Wooka” Woon to be split among senior painters and dockers, while Baldy Blair and his sidekicks Steve Nittes and Al Jones got close to $100,000 each: the price of a dozen ordinary houses at the time.

Blair was a Melbourne painter and docker who’d graduated into a life of crime from the hard streets of Richmond, Collingwood and Port Melbourne, running waterfront rackets, stealing cargo and smuggling contraband.

After the Melbourne scene had got too hot for Baldy in the mid-1960s, he went to Sydney and took up armed robberies. He also took up with young Larry’s beautiful mother, Patricia, a former competitive synchronised swimmer who dressed elegantly, spoke well — and, in her adoring son’s estimation, could have succeeded in anything she wanted but instead chose the adrenaline rush of the outlaw life, from shop-stealing to high-end jewel heists that made international headlines.

Baldy Blair became the only father young Larry ever knew. Half a century on, Baldy’s abduction and death at the hands of treacherous “friends” still haunts the little boy left behind, who is still facing up to the shadows of his past.

This is real life and death, real fear and loathing, not entertainment. After his father vanishes, obviously murdered in nightmarish circumstances, 11-year-old Larry and his mother are on the run — not from the law, but from the killers who want to catch them to get Baldy’s cut of the stolen cash.

That’s when they board the plane to Melbourne, heading for the Frankston hideaway. There’s little doubt the toecutters worked with a corrupt police sergeant, real name Fred Krahe, named in the book as Kaiser.

It is highly likely that fellow police leaked Krahe the information that led the gang to the motel where the pair were hiding after they escaped the Melbourne flight.

Like most crooks, Baldy Blair is a risk taker. Immediately after the robbery, the family bolt to the Coober Pedy opal fields but Baldy soon returns to his Sydney haunts, a fatal error. When he goes back to the Oceanic Hotel in Coogee, his “mates” invite him to look at some stolen goods in a van, then abduct him.

As far as Larry can establish, Baldy is taken to an empty warehouse and there meets his terrible end. His two fellow-robbers, Jones and Nittes, survive. Jones gets a long sentence and is stabbed in jail; Nittes ends up in England, where he dies an old man in late 2021.

“Elderly associates of my father who still haunt Sydney and Melbourne today, reluctantly filled some of the remaining gaps,” he writes.

“There were many. There always will be; outlaws don’t keep diaries.”

Ten years after the Mayne Nickless robbery, Larry’s mother and two men stole the priceless Golconda d’Or diamond from its locked display case in front of 80 people, switching in a worthless glass fake.

It was a brilliant heist but Larry Blair was never tempted to be a crook or even to gamble. He’d seen the damage done.

The Outside, by Larry Blair and Jeremy Goring. Published by Penguin Random House. RRP $36.99