Andrew Rule: How a ‘nice boy’ hunk became a violent bikie fugitive

Nothing about how “nice boy” model Hasan Topal spoke or acted suggested the murderous rage or malice that leads to blood, bullets and battered bodies.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

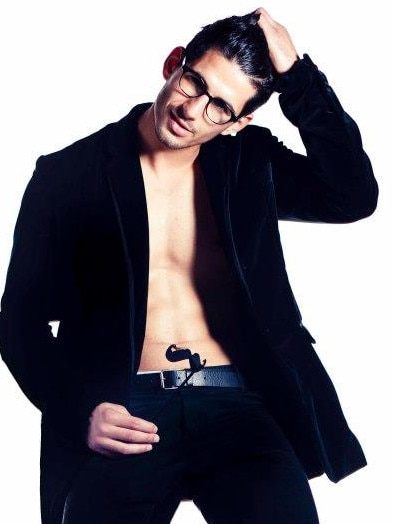

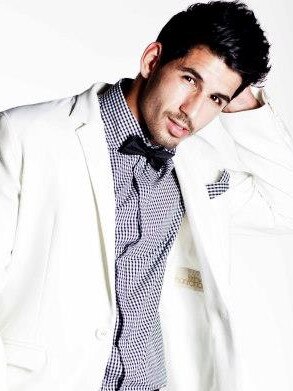

By fashion agency standards, the Turkish kid was just another pretty face. Among some of the more androgynous waifs pouting for pay, he was on the masculine side of handsome — but no more brooding than most of the faces at Chadwick Models.

Before and after the camera stopped clicking, nothing about the way he spoke or acted suggested the murderous rage or malice that leads to blood, bullets and battered bodies.

“He was gentle, polite and genuinely nice,” says a talent scout who handled the young man’s part-time modelling work. “All ‘please’ and ‘thank you’.”

So it came as a huge surprise to everyone at Chadwick’s Melbourne branch a few years later when their muscular former model, Hasan Topal, was filmed in very different circumstances.

Plenty of models fancy stepping up to acting so they can play at being more than a clothes horse.

Chadwick, in fact, boasts in its promotional blurb that it “initiated the careers of well-known names like Elle McPherson, Travis Fimmel and Rachel Hunter.”

All three went on to act – notably Fimmel, the Echuca farm boy who quit milking cows to star in the global hit series, Vikings. Fimmel played Ragnar Lothbrok, a make-believe warrior covered in tattoos applied by make-up artists to play a made-up story.

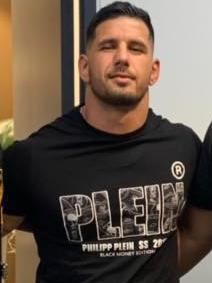

Hasan Topal, on the other hand, became a violent outlaw bikie, suspected killer and international fugitive. His tattoos, like the violence, were real. But he seems to have an actor’s flair for the dramatic.

If there’s one event that marks the change from the “nice boy” the talent scout knew, it was in August 2017, when Comanchero bikies gathered in a strip club in the Canberra suburb of Fyshwick after their annual national run.

The trouble starts with an argument in the club’s smoking room, then spills into the main bar and ignites an ugly riot, all caught on camera.

It is 3am but the club is full. More than half the crowd are heavily muscled men wearing Comanchero tracksuit tops, T-shirts or hoodies.

Topal is one of four Comanchero later charged over the brawl. He attacks a man, punching him to the floor. Then he pulls a stunt that looks as if it’s scripted for Mel Gibson or Schwarzenegger: he smashes a glass on his head, drawing blood, then peels off his shirt and renews the attack on the man on the floor.

When the victim regains consciousness and tries to stumble away, Topal punches him in the head.

He and three other Comanchero members are charged and plead guilty to affray in the ACT Magistrates Court.

The prosecutor says the extreme, prolonged and gratuitous violence is in the worst category. Although Topal didn’t start the brawl, he was a willing participant who ignored opportunities to step away, including being held back, but kept punching on. A display of sustained viciousness.

The defence says Topal acknowledges he acted inexcusably. This from a man with a health and fitness degree, a gym owner with a good employment history and family support.

The magistrate rules that Topal should know better, and sentences him to 10 months jail, to be suspended after five months. Three other Comanchero — Paea Talakai, 27, Nuulua Sooa Levi, 55, and Peniamina Elia, 34 — are also jailed.

Sentencing Topal, the magistrate says he has good employment prospects and urges him to consider his future and quit the gang.

It seems he takes only half the advice. As soon as Topal gets out of jail, he considers his future closely – and concludes it will be more secure a long way from Australia. He flies to his parents’ homeland of Turkey and hasn’t been back since.

Quitting the gang is another matter entirely. Because even if he walks away, the gangs might not walk away from him. Neither will police.

It seems both law enforcers and lawbreakers are waiting for Topal’s return. His critics on both sides seem confident that the brawl was the least of his offences, which explains why he’s a fugitive on the other side of the world.

So, as the Paul Kelly song goes, what makes such a sweet guy turn so mean?

Any answer to the question of what turned a model citizen into violent thug would have to include the word “drugs” – as in the sort of drugs that change people’s behaviour when they use them.

That’s a cocktail that starts with steroids and is topped up with cocaine and the biker staple, methamphetamines. All of which command so much money on the black market that rival gangs compete to import, make and sell them.

When it comes to using and distributing drugs, outlaw biker gangs like the Comanchero – and many others – are in it up to their tattooed necks. It explains a lot about the same gangs’ descent into displays of extreme violence in recent years.

The story of Hasan Topal, pieced together from underworld gossip and police intelligence, builds into a violent frenzy in the months before the Canberra brawl.

On the night of May 2, 2017, a skinny and harmless young man named Muhammed Yucel is leaving a friend’s house in the Melbourne suburb of Keysborough after spending the evening gaming with his mates.

About 10pm, he lifts the garage door to leave. The shooters lurking nearby didn’t have time to look at him because if they had they could hardly have mistaken him for the man that police are sure was their intended target.

They open fire immediately, hitting the innocent Yucel in the chest. He falls back inside before collapsing but the shooters keep firing, wounding two of his terrified friends.

A week later, police raid another house in the same street and arrest a burly, heavily muscled Mongol bikie associate named Farshad Rasooli, a man who surely weighs nearly twice as much as Yucel. Rasooli, suddenly keen to change address, is charged with possession of an illegal handgun, $70,000 cash, steroids and other offences.

Meanwhile, the search for the gunmen centres on a Jeep Cherokee used in the shooting, dumped at Cranbourne and torched. But the bumbling killers fail to burn it properly, so police retrieve a cloned number plate they later prove was mocked up on a printer at a northern suburbs gym run by Topal.

To kill the wrong man is one thing. To do it again shows criminal recklessness that’s a huge threat to public safety.

The following month, in June 2017, someone shoots up the Dream Drives luxury car hire business in Burnley St, Richmond.

Bullets recovered at the car place came from the same gun that killed Yucel. Police discover that Topal had earlier visited the business and bashed an employee over a $20,000 “contract dispute”.

The standover visit was possibly connected to claims made by disgruntled clients that Dream Drives (since closed) was accused of withholding large cash deposits for hired luxury cars. Then again, it could have been something else entirely.

Topal’s negotiation style was straight from the Tarantino playbook. He reportedly threatened: “I’m going to start beating you guys up one by one and then destroy your cars one by one.”

There’s a pattern here.

On the night of July 28, a Friday, a convoy of Bandido bikers is heading south on the Bolte Bridge when an unknown shooter opens fire from an overtaking station wagon.

A 40-year-old Bandido from Sunbury is hit in the chest, crashes and is taken to the Alfred Hospital. One of his fellow riders later goes to Royal Melbourne Hospital with gunshot injuries.

The suspect station wagon is found burnt out in Keysborough. The main suspect is Hasan Topal, partly because road cameras show the wagon was fitted with cloned number plates like the Cherokee in the Yucel shooting. (As was, incidentally, a getaway car used in the shooting of fruiterer Paul Virgona on the Eastern Freeway two years later.)

Less public but possibly more risky than the Bolte Bridge outrage was the attempted shooting of heavyweight bikie Mark Balsillie earlier that month. Balsillie, a Lamborghini-driving Brighton identity, was still a Comanchero at that point – but on the outer with a senior figure in the club. He apparently reconsidered his club affiliations after the shooting, apparently interpreting it as a vote of no confidence.

It might be that Balsillie was already on good terms with the Mongols, as he immediately joined them and has since become national sergeant-at-arms. He is regularly pictured with the bullet-scarred Toby Mitchell and his mate, Jake “Push Up” King.

If, as police and others suspect, Topal was involved in all four incidents, it was a hectic few months for him. But there’s more.

On August 16, a Wednesday night, a young boxer recently arrived in Victoria from Perth visits a friend in Kurrajong Rd in the vibrant, multicultural and colourful outer suburb of Narre Warren.

The visitor’s name is Zabi Ezedyar and he has no police “form” of any consequence. But he is shot dead outside the house.

Police believe that Mohammed Keshtiar, a Mongol associate living at the Kurrajong Rd address, is the intended target. So it’s another deadly debacle.

The Comanchero run starts that week. The brawl in Canberra, just four nights later, is the sixth incident in 16 weeks, the climax of an extraordinary string of murderous outrages.

“And they’re only the ones we know about,” a detective later mused. Police are not alone in rating Topal as the common denominator.

But what was behind it?

Despite allegedly twice murdering the wrong people, Topal still rose up the Comanchero hierarchy swiftly.

By April, 2018, it was widely reported he had been installed as commander of the gang’s southern chapter. It was, according to one seasoned police investigator, a reward for doing some “heavy lifting”.

Some of that lifting, police believe, was on behalf of the Comanchero national president,

the enigmatic Mick Murray.

It seemed Topal was prepared to do whatever it took to leapfrog up the ranks.

“He came out of nowhere,” the source said. “All of a sudden, he came up on the radar as a young, aggressive up-and-comer. I think he was trying to prove himself worthy of being Mick’s lieutenant.”

Meanwhile, older heads wondered if blind violence was good for business.

Amad “Jay” Malkoun, the gang’s former Victorian head, living in Europe at the time, was reportedly at odds with Murray. This enmity reflected deadly divisions in the club.

For a young Turk whose ambitions and ego possibly outstripped his ability, it was a chance to climb the greasy pole of outlaw politics. A risky pastime, as he might discover if or when he returns.

Police are keen to see him. “If he wants to come home,” says one investigator, “we’re happy to pay his airfare.”