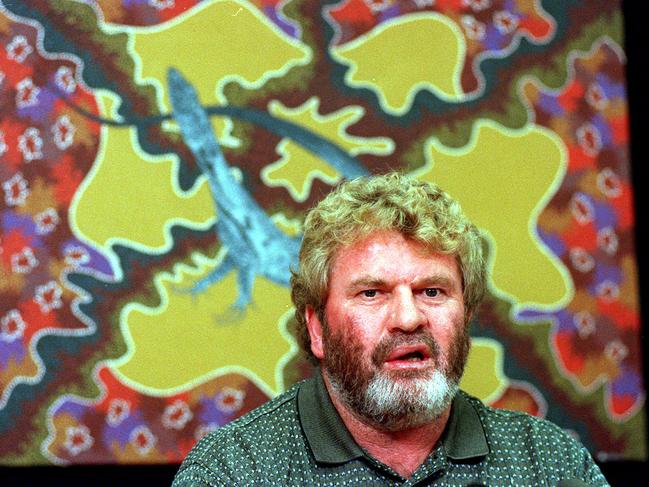

Andrew Rule: Geoff Clark’s criminality as ingrained as his belligerent sneer

As a boy, Geoff Clark was so embarrassed by the sandy hair and blue eyes he’d inherited from his Glaswegian father that he’d rub mud on his face. That distress might explain what turned him into a rapist, a thug and a brazen thief.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The Aboriginal people I grew up with at Lake Tyers had a word for frauds like Geoff Clark. They called them “gubbahrigines”.

Gubbah is their word for whites, and splicing it with “Aborigines” skewered their target as a fake — a white fella pretending to be Koori.

For all his bluster and his bullying, his bikie boss machismo, deep down Clark knew from childhood that he was different from the rest of the mob at Framlingham, near Warrnambool.

One of his black female cousins — not the one he raped, as it happens — told me she recalls the young Clark arriving at the settlement from the city as a boy.

He was so embarrassed by the sandy hair and blue eyes he’d inherited from his Glaswegian father that he’d rub mud on his face to try to fit in.

Nothing else about Clark makes me pity him, but that does. It might explain what turned him into a bash-artist, a rapist, a misogynist and a calculating and brazen thief.

Not that any “nature or nurture” hand wringing eases his victims’ anguish. His criminality now seems as ingrained as his belligerent sneer.

I knew men who did time in Pentridge with his biological father, “Ginger” McIntosh — a standover man, street fighter and armed robber. The Scottish hard man would occasionally visit Geoff and his mother at Framlingham after she’d quit the streets of Fitzroy.

McIntosh drove a Pontiac with a pistol in the glove box, according to that same cousin, a daughter of the well-liked and respected Framlingham elder, the late Banjo Clarke.

Greens, anti-gun activists and aggressive civil libertarians might now realise the sort of strange bedfellow they once automatically showered with praise for no reason other than one of his great grandparents was indigenous.

That sort of blind loyalty was plain dumb and the remnants of Clark’s gullible city supporters should be humiliated, if they’re honest, by the final disgrace: the latest “revelation” that their rusty hero is as bent as a boomerang.

Even after spending vast sums of other people’s money (hello, taxpayers) defending himself in a series of secret trials this year, Clark has just been found guilty of almost $1m worth of theft and deception.

Unsurprisingly, he plundered the Aboriginal organisations he once led. Ones in which he still held the sort of sway that a John Setka or Toby Mitchell has in the building unions.

Will Clark’s silvertail supporters be honest enough to admit they were wrong? There’s a deafening silence, so far, from the earnest and influential defenders who leapt to support him against what they characterised as an unwarranted “attack” when, in 2001, this reporter put together Clark’s horrifying history of raping girls and women.

Not a word, yet, from one prominent jurist, still licking wounds after the High Court spanked him and another on-trend judge in a high profile case. He was very vocal in 2001.

Same goes for an obscure author whose dreary and mostly unread work was published by a wealthy vanity publisher who now may regret it. She devoted a very ordinary book to defending the indefensible.

The Clark expose attacked by these jurists and their fellow travellers, by the way, began as a neutral profile of a powerful political figure, the highly paid and influential chair of what was then the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission.

It was a story that even an amateur could have uncovered merely by asking questions of those who knew him best — indigenous people he exploited and robbed while pretending to represent them to the wicked authorities that paid him a State Premier’s salary for a position nailed down with the votes from a handful of people. Tammany Hall stuff, right down to bribes, guns and violence.

Fact is, guns and violence always appealed to Clark. When a Warrnambool Standard reporter went to Framlingham to do a story about Clark’s gang illegally plundering the state forest for firewood to sell for cash, he heard a click next to his ear.

The reporter turned to find himself staring down the barrel of a gun held by the gloating Clark, who said: “You’re going to write a nice story, aren’t you?”

That happened in the 1970s. But when the same reporter, by this time safely living in Melbourne, was urged to write that story in 2001, he refused. Not because it wasn’t true but because it was — and he was still scared that Clark would hurt him.

He wasn’t alone. Nearly everyone I spoke to about Clark in western Victoria in 2001 was nervous of him. Guns weren’t all. They feared their houses would be burned down.

But Clark wanted more firepower than a pistol in the glovebox. He once tried to bring back an illegal automatic military rifle from North America and got angry when Customs confiscated it in Darwin. Like too many thugs the world over, he posed as a freedom fighter but was in truth a bandit.

No one who knew him well back then will be surprised at the latest revelation of a long list of crimes, even if many have been papered over with the sort of money and influence he used to be able to conjure up at will.

As a footballer, skilled but a brutal bash artist, he was able to get charges “fixed”. When he played for a Warrnambool team, a senior policeman was a powerbroker in the league.

Despite Clark’s evasive tactics, some mud stuck. When I obtained a copy of his criminal record dating back to his teens, it showed he’d done time for a violent crime and had been charged with many other offences but had mysteriously dodged further jail or convictions.

Why? He was a useful football enforcer. And he was so involved in the west coast drug scene that he made a useful police informer. A give-up.

One particularly ugly incident was when a local “heavy” matching Clark’s description set up a visit from an Adelaide drug dealer then bashed and robbed him and raped his girlfriend in a Warrnambool hotel room.

The consistency of Clark’s criminal behaviour in the 23 years since this reporter first exposed it in 2001 is hardly surprising.

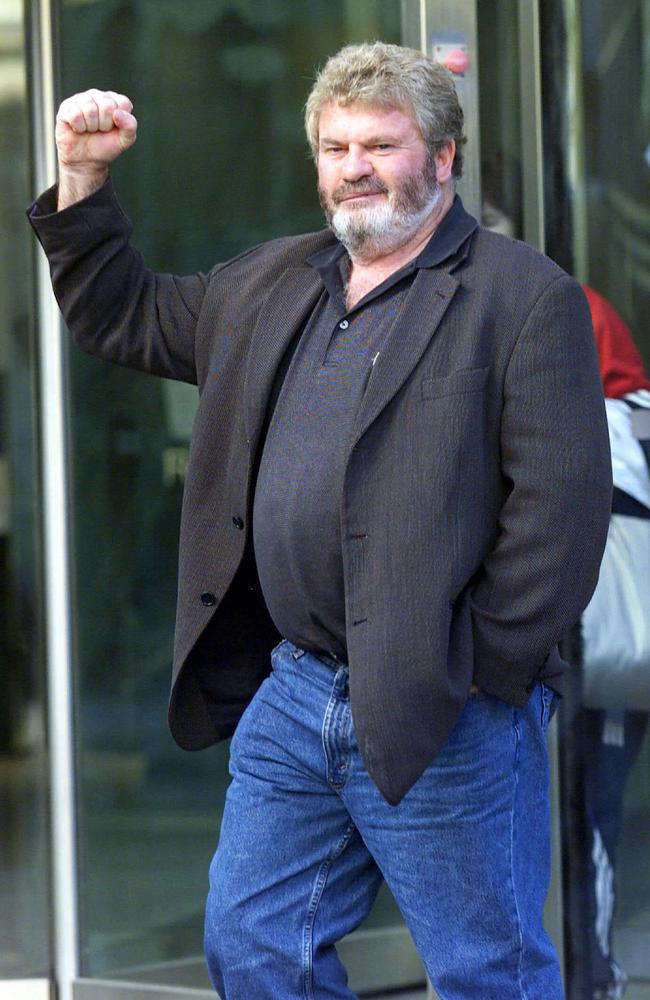

One year he’s sued by a rape victim. Another, he’s accused of fraud and theft and thuggery of all sorts. And, finally, after years of investigation, a dogged police operation has managed to trap the big dog of Aboriginal politics.

What his defenders failed to understand in 2001, and probably still do, was that it was never about race. It was about the content of his character and the failure of the law to protect those he preyed on.