Andrew Rule: The freak with the streak up there with Australian sporting royalty

Tensions rose with every Winx victory as her unbeaten streak stretched from 2015 to 2019, but while the Bradman of racing could take the stain, her connections couldn’t.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

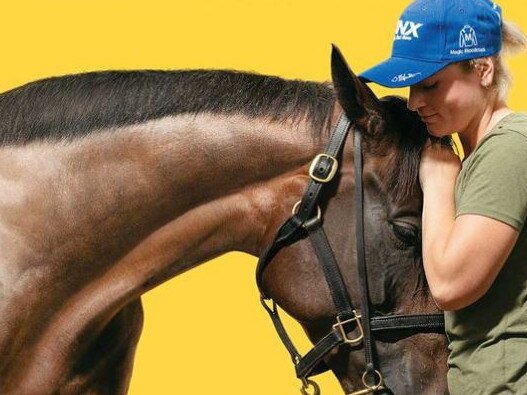

At her peak, Winx was the freak with the streak. By the time the world’s greatest racehorse won her third Cox Plate and 22nd consecutive race in 2017, she was a highwire act with millions watching and waiting for her to slip. She didn’t.

Even before the climax of her astounding career, she was the Bradman of racing. Then she won a fourth Cox Plate — a record unlikely to be broken.

There was nothing more to prove but she did anyway, franking her superiority with a fourth unbeaten autumn, a victory roll after her fourth unbeaten spring, nailing 33 straight victories before Team Winx stopped tempting fate.

Tension had risen with every win as she stretched the streak from the autumn of 2015 until the autumn of 2019. Winx could take the strain but her connections couldn’t.

As anguished trainer Chris Waller says in the new Winx film: “Where was the red line? When did she break?”

But she didn’t, largely due to Waller.

In more than 50 years of watching the passing parade of sporting highlights, this reporter ranks Winx’s unbeaten exit with the pin ups of a lifetime. From a teenage Lionel Rose heisting the world bantamweight crown in 1968 to an even younger Shane Gould’s swag of swimming medals at Munich in 1972; from David Hookes making five straight boundaries at the MCG in 1977 to Cathy Freeman’s golden Olympic moment in 2000.

You want tear-jerkers? Try Gillian Rolton remounting her horse Peppermint Grove in the Atlanta Olympics with a broken collarbone and punctured lung to clear another 15 jumps and nail down gold for Australia. Better judges than this one say it’s the bravest thing they’ve seen in sport.

I was there the day Damien Oliver won the 2002 Melbourne Cup on Media Puzzle just days after his brother Jason died following a track fall. It was probably the most touching scene on an Australian racecourse — until Michelle Payne stole the Cup and a nation’s hearts on Prince Of Penzance in 2015.

But trying to recreate such magical moments doesn’t work. Racing, like boxing, triggers huge emotions because it demands bravery and imposes risk. Elite boxing and racing is almost impossible to confect for the camera because nothing’s as good as the real thing. Except maybe DeNiro in Raging Bull.

Sadly, but not surprisingly, the attempt to make a fictionalised feature film of Damien Oliver’s Cup ride was a well-intentioned dud. The Payne film, Ride Like A Girl, was nearer the mark. So when Victorian-born filmmaker Janine Hosking pitched the idea of a Winx film, it was always going to be a feature documentary that would bring distilled reality for the big screen.

As someone once said, truth might be stranger than fiction — but it needs a better editor.

In Hosking, the Winx story got exactly that: someone who could sift through a truckload of footage, shoot key interviews then weave something greater than the sum of its parts. Like turning lead into silver.

A horse can’t talk, let alone sing. And even for a horse, Winx was more the businesslike athlete than lovable character. She’d happily nuzzle children but turn her rump towards adult visitors to the stables.

To make something more than a skilful mash-up of Winx’s greatest hits, Hosking had to take the audience beyond and behind the action. Because I’d interviewed dozens of people connected to Winx to write a book, she asked me to help.

The result: A Horse Named Winx, which opens in 135 cinemas around Australia this week and next. And it’s a roller coaster, not the scenic route.

As with subjects like Ayrton Senna and Amy Winehouse, we tend to think we know the story. But it’s all the bits we don’t know that hit home. The promotional tagline for A Horse Named Winx says it perfectly: “The fairytale you know. The story you don’t.”

Behind the procession of wins is the behind-the-scenes story of those hectic years. To outsiders, Chris Waller’s horse training operation might have looked calm on the surface, but the stress of keeping it that way gnawed at his peace of mind.

We know this because he says so. As does his wife Stephanie. The highs and lows of life as Winx’s trainer are laid bare in edited excerpts from revealing interviews with the Wallers.

Same with Hugh Bowman, Winx’s deadly calm jockey, one of the rare professional sportsmen who doesn’t speak in cliches or sugar coat reality.

Then there are the owners, of course, who differ from each other but are not so much a rags-to-riches story as a rich-to-richer story.

The film captures how a modern racing stable is a truly diverse enterprise.

In Winx’s case there’s Amir Attaollahi, the cheerful Indian horseman who first rode Winx in a breaker’s yard. His cameo appearance is a gem.

There’s Winx’s original strapper Umut Odemislioglu, the quiet Turk who gave the impression he’d die before he’d let any intruder harm the filly he looked after from the day she arrived as a green two-year-old.

When Winx graduated to needing a second minder, enter chirpy Candice Persijn, the Canadian-born stablehand whose irreverent take on being Winx’s “bitch” (her words) is a joy.

Candice reveals the story of how Winx once escaped from being hosed down in the wash bay. Luckily, the priceless mare didn’t take any harm from it. Otherwise, Candice jokes, she would have had to flee the country.

But a success story, likewise a good film, needs obstacles. Winx suffered two big ones, neither of which the public knew about at the time.

The autumn after Winx won her first Cox Plate, a routine X-ray revealed a tiny bone chip in one leg — the near fetlock joint, in human terms the left ankle.

The chip was the size of a child’s fingernail and probably as harmless — unless it moved from where it flaked off and became a risk, like a tack working its way into a Ferrari tyre.

On a lesser horse, it would be left unless it caused lameness. But expert vets urged Waller to let them remove it, just in case. His choice was to operate and hope she would recover in time for her second Cox Plate campaign — or leave it and hope the chip didn’t move and wreck her spring preparation. Or her whole career.

Waller was torn. He didn’t want to stir up the sort of headlines the story would make. Already spread thin over 15-hour days, he wouldn’t cope with the inevitable outcry.

So, on April 11, 2016, they operated in secrecy. The keyhole surgery took only minutes but required general anaesthetic. As soon as she recovered, Winx was trucked secretly to her usual spelling farm. Like a rockstar headed for rehab, she travelled incognito, and was dubbed “Skinner” for the next 10 weeks.

Under Waller’s direction, farm manager Olly Koolman streamlined the rehabilitation program to shave time off it. Waller was so cagey about the story leaking he didn’t email anything — simply scrawling notes on paper and getting someone else to photograph it to send to Koolman.

Operation Skinner was a race against the calendar. To be fit for the 2016 Cox Plate, Winx had to be fit to run in lead-up races. By June 3, she was saddled for the first time in two months just 17 days before she was due back at Rosehill to start her “prep.”

It worked. It was only after her return to Rosehill that Waller told the stewards about the operation. They called an “inquiry” into why they hadn’t been informed earlier.

It was then that Waller realised the truth: “Winx wasn’t just our horse any more.” After nine straight wins, she was public property. He could hardly have guessed his ordeal was just beginning. Every win was a relief, not a celebration.

Winx would stay sound for the rest of her career — 24 more straight wins including three more Cox Plates. When she went to stud in the spring of 2019, her connections could have been forgiven for feeling relieved that the pressure was off.

But the thoroughbred horse, even one as sound and tough as Winx, is a delicate animal. Her greatest test would come at Coolmore Stud in the Hunter Valley the following year.

The Disney fairytale would have the virgin queen meeting a handsome prince, producing perfect princelings and princesses of the racing world and living happily ever after. But the real story, the one only a few people then knew, was otherwise.

Winx’s mating with the most desirable stallion in the land, I Am Invincible, produced a stillborn foal in 2020. Worse, the difficult birth brought on a form of colic that is often fatal. Tearful owners prayed as a brilliant veterinary team fought to save her life, forced to try a surgical procedure that could easily end badly.

The pure heroine of the racetrack was now a heavily bandaged invalid, contained for months in a loosebox, equivalent to a hospital bed. Many horses would not have survived. But Winx did, and ultimately thrived.

When they let her out at last, she bucked around the paddock and galloped past her mate. If the first Winx miracle was freakish athletic ability, this was the second Winx miracle.

Coolmore boss Tom Magnier nails it perfectly.

“She had the will to win. But she also has the will to live.”

A Horse Named Winx opens in select cinemas today, nationally on September 5