The case against the Calabrian mafia mobsters, suspected of murdering AFP’s Colin Winchester

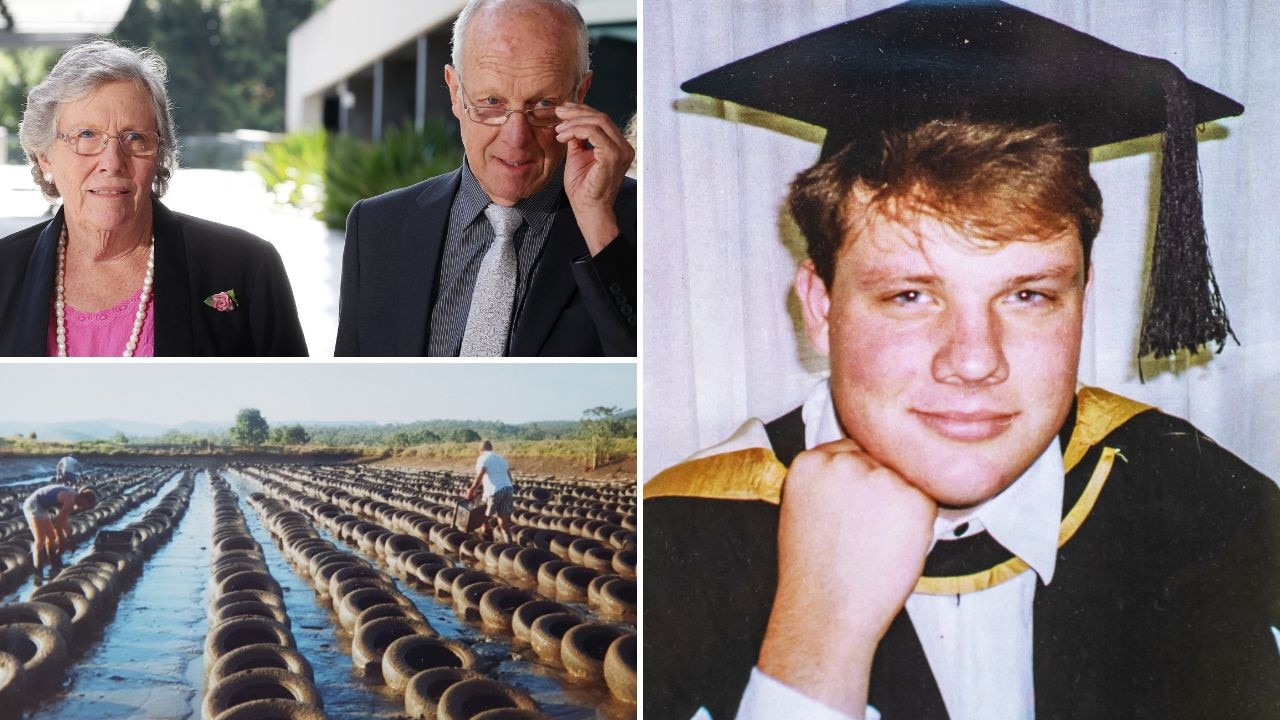

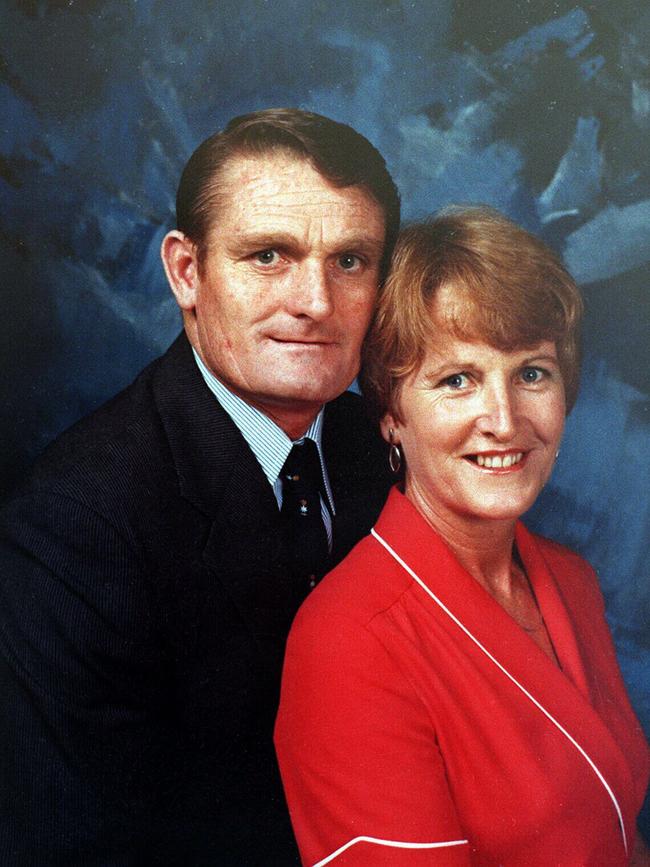

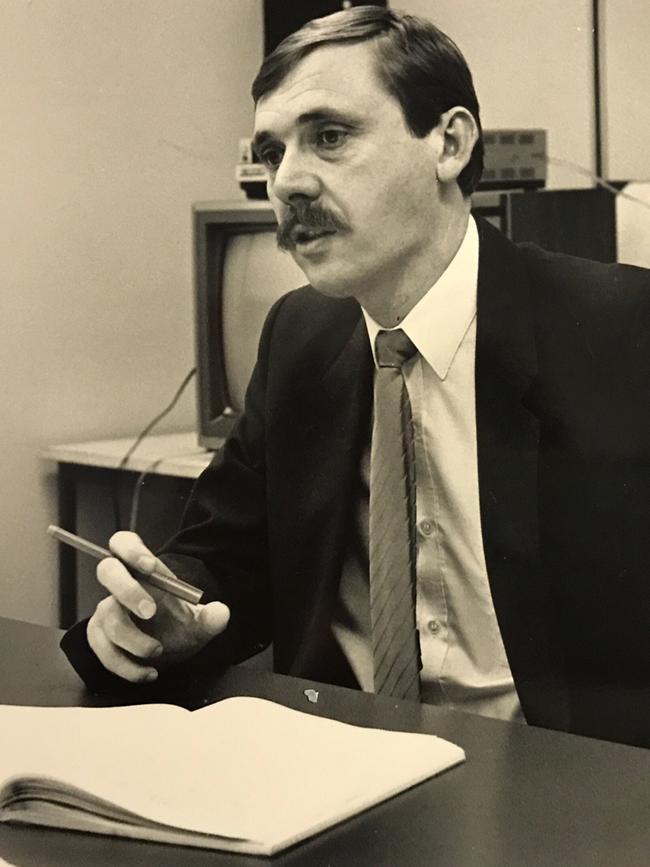

It was a murder that shocked Australia — AFP assistant commissioner Colin Winchester was shot dead outside his Canberra home 30 years ago. And some remain convinced the assassination was the work of the Calabrian mafia.

Cold Cases

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cold Cases. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was difficult to imagine that a disgruntled former public servant could be responsible for the shooting murder of a top cop.

Which is why some people remain convinced the hit on Australian Federal Police assistant commissioner Colin Winchester was the work of the Calabrian mafia.

He remains the most senior police officer ever murdered in Australia and it is 30 years this week since he was gunned down outside his Canberra home.

The January 10, 1989, assassination was huge news at the time.

PART ONE: WITHHELD EVIDENCE COULD PROVE SHOOTER

LISTEN TO THE LIFE AND CRIMES PODCAST ON ITUNES

Mr Winchester probably never knew what hit him as he prepared to climb out from behind the wheel of his cream Ford Falcon about 9.15pm.

He had just driven his unmarked police car into the driveway next door to his Lawley Street home in the Canberra suburb of Deakin. He had an arrangement with his elderly widowed neighbour to give her some security by leaving his car in her driveway overnight.

The waiting assassin had the cover of darkness, as well as shelter provided by Deakin’s many tall gums and shrubs. He watched Mr Winchester’s car slow down and stop before creeping up from behind.

Bringing his .22 Ruger rifle to his shoulder, he waited for the top cop and father of two to open the car door and start getting out before making his move.

The first shot was fired into the back of Mr Winchester’s head from a distance of between 400mm and 600mm, meaning the muzzle of the weapon was in the vicinity of the centre door pillar when the trigger was pulled.

To make sure of death, a second shot was pumped into 55-year-old Mr Winchester’s brain through the side of his head, just above the right ear. An autopsy later revealed either shot would have been fatal.

The killer operated swiftly, departing the murder scene without being spotted and before Mr Winchester’s wife Gwen, who was inside the house, discovered her husband’s plight.

The Winchester murder was huge news again in December last year when David Harold Eastman — the man charged and later convicted in 1995 of murdering Mr Winchester — was acquitted at his retrial after spending 19 years behind bars.

The not guilty verdict in the ACT Supreme Court came after a six-month trial, during which jury members heard from 127 witnesses and had statements read out from 41 others.

Mr Eastman, now aged 73, was released in 2014 after a judicial inquiry found the original guilty verdict was based on “deeply flawed forensic evidence”.

The Herald Sun’s True Crime Australia yesterday detailed the case against Mr Eastman.

WHY MOBSTERS WERE KEY SUSPECTS

Calabrian mafia mobsters were suspects in the 1989 Winchester murder from day one.

They were top of the list because of Mr Winchester’s initial role in one of the most controversial police sting operations ever.

That involvement began in 1980 as a result of an Italian man we will call Mr X, because his name has been suppressed by the ACT Supreme Court.

Mr X was being cultivated as an informer by AFP Det-Sgt Brian Lockwood. During one of their discussions, Mr X said he had been approached by Canberra-based members of the Calabrian mafia to grow a crop of marijuana on his Bungendore property in New South Wales.

The Italian organised crime secret society is variously known as ‘Ndrangheta in Calabrian dialect, L’Onorata Societa or the Honoured Society by some Italians, La Famiglia or the Family by others and simply the mafia by most in Australia.

Since the 1990s, the Australian arm has increasingly been called the Calabrian mafia, with reference to the Calabrian region of Italy, to differentiate it from the traditional Sicilian mafia.

Det-Sgt Lockwood told Mr Winchester about Mr X being asked to grow dope by senior Calabrian mafia members and that Mr X was willing to do it and also provide information to police on the mobsters behind it and their distribution network.

Because the crop was going to be grown in NSW, Mr Winchester then spoke to a senior officer at the NSW Bureau of Crime Intelligence and between them they hatched a plan to allow the marijuana crop to proceed with a view to gathering intelligence on those behind it.

They also hoped Operation Seville, as it was dubbed, would result in arrests if they could be made without jeopardising the safety of Mr X.

What they agreed to do was allow Mr X to plant, grow and harvest a huge marijuana crop on his Bungendore property and for Mr X to tell the Calabrian mafia members he was paying corrupt police to ensure the crop wouldn’t be seized.

It was also agreed that Mr X would not have to give evidence against any persons charged as it was determined that if he got in the witness box, or was identified in any way as an informant against the Calabrian mafia, he would be killed.

Mr Winchester was gambling that surveillance of the operation, coupled with information provided by Mr X, would lead to the exposure of Australia’s biggest drug gang and provide police with intelligence on the workings of the Calabrian mafia.

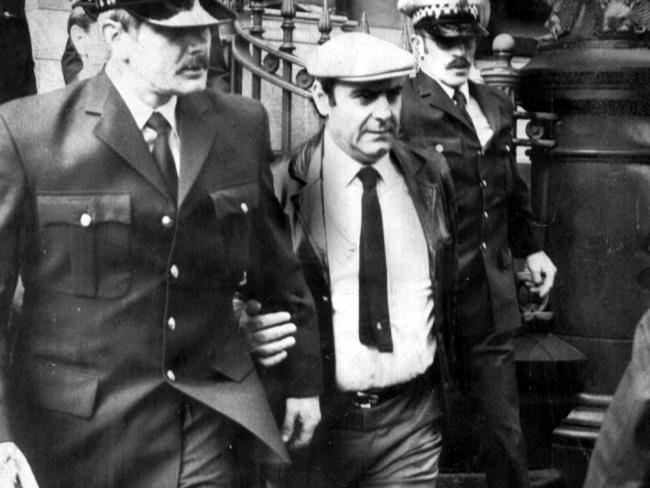

A positive, but unintended, result from the Bungendore crop was the March 1982 arrest in Victoria of Gianfranco Tizzoni with a car boot full of marijuana.

The AFP and NSW officers involved in Operation Seville had expected Tizzoni to turn right towards Sydney and had set up surveillance on that route, but when the car turned left towards Melbourne they had to involve Victoria Police.

Tizzoni then became an informer to Victoria Police in return for having the drug charges dropped.

It was information provided by Tizzoni which led to Victoria Police establishing it was the Griffith cell of the Calabrian mafia that ordered the 1977 execution of anti-drug campaigner Donald Mackay and that Melbourne painter and docker James Bazley was recruited to carry out the Mackay hit.

The “mafia did it” angle in relation to the Winchester murder was extensively investigated by the AFP and the ACT coroner during the Winchester inquest, with neither finding any evidence of the Calabrian mafia being involved in the top cop’s death.

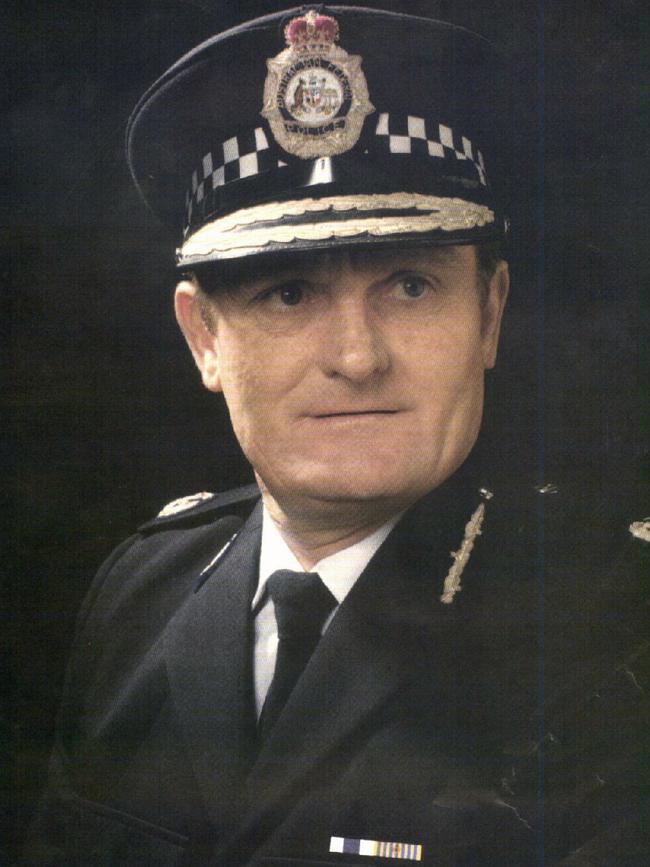

But speculation persisted so in February 1992 the then AFP Commissioner, Peter McCauley, asked the then Victoria Police Chief Commissioner, Kel Glare, to review the AFP’s Winchester investigation.

THE MCKENZIE REPORT

Respected Victoria Police detective chief inspector Ken McKenzie was appointed to lead a team to review the AFP’s handling of the investigation, including into possible Calabrian mafia involvement, and he delivered his findings after a comprehensive six month probe.

The confidential McKenzie review report, which has been seen by the Herald Sun, found Mr X used a cover story with the Calabrian mafia members he was dealing with over the crop that he had corrupt protection for it from Mr Winchester and Det-Sgt Lockwood — a false cover story the honest Mr Winchester and Det-Sgt Lockwood went along with so the mobsters would go ahead with the crop.

“It further appears the offenders believed Winchester and Lockwood were corrupt and would be paid for providing protection,” the October 1992 McKenzie report said.

“The crop, known as Bungendore 1, was cultivated in late 1981 and harvested in early 1982.

“The offenders gave Mr X $23,500 cash and 40 pounds of marijuana for the ‘corrupt police’.

“The cash was paid into consolidated revenue and the marijuana eventually disposed of.

“It is not known if this was the full amount Mr X was given for the ‘corrupt police’ or whether he retained part of the payment. There was no effective control over Mr X’s activities.

“In late 1982 Mr X claimed that he was again approached by his Italian associates and asked to grow another crop at Bungendore.

“After further consultation the Bungendore 2 crop was approved. The scenario of corrupt police was again apparently utilised.

“Winchester was not involved in Operation Seville after September 1982, which was in fact before Bungendore 2 got under way.

“It is doubtful that the offenders would have been aware of this and apparently believed he was still providing protection.

“Bungendore 2 was aborted in early 1983 after the crop had been ripped off on three occasions by outside criminals.

“In 1985, Mr X was arrested for his involvement in a crop at Guyra, NSW. He approached NSW police stating that he was prepared to give evidence against the participants in Bungendore 1 and 2 and the Guyra crop in return for protection.

“The National Crime Authority became involved and took over the investigation of the three crops.

“The NCA organised indemnities for Mr X for his involvement in Bungendore 1 and 2 and Guyra in return for his evidence.

“A brief was prepared against 11 Italians who became known as the Bungendore 11.

“They first appeared in court in April 1988 and were adjourned to late 1988. A committal hearing was eventually set for the Queanbeyan court on February 6, 1989 (a month after the Winchester murder).

“Mr X was most uncooperative at court and virtually refused to give evidence for the prosecution.

“The charges relating to Bungendore 2 were dismissed.

“The accused were committed on the charges concerning Bungendore 1 but these were not proceeded with.

“The review team has been unable to identify any evidence linking any member of the Italian community to the murder.

“The investigation into this segment was extensive. It was carefully scrutinised at the inquest and within the media.

“Forty six individual suspects were identified and investigated. No evidence linking these people to the murder has been located.

“It is significant that an investigation of this magnitude failed to disclose any evidence.

“The investigation into the Italian segment was subjected to intense media and community speculation.

“At the completion of the investigation and subsequent inquest the speculation remains unsubstantiated.

“The review team has not located any material to raise the classification higher than mere speculation.

“Undoubtedly the proponents of the ‘mafia hit’ theory will not be swayed by the lack of evidence supporting their position.

“There are various popular motives to explain why members of the Italian community may have murdered, or ordered the murder of, assistant commissioner Winchester.

“The most popular is that the Bungendore 11 were under the impression Winchester was corrupt and when they were charged by the NCA they believed he had betrayed them.

“This scenario is difficult to support as it appears that by 1989 the Bungendore 11 were well aware of Winchester’s legitimate role in Operation Seville.

“As the Coroner observed, ‘Those charges were adjourned to the latter part of 1988, by which time it was made known to all defendants that Mr X was to be the prime witness against them, and statements which he had made fully disclosing his relationship with Winchester and other members of the AFP were circulated to the defendants through their legal advisers’.

“It has also been advanced that Winchester was murdered to prevent him giving evidence against the Bungendore 11.

“There was no intention of Winchester giving evidence for the prosecution and it appears that a number of the accused were aware of this.

“There was no admissible evidence that Winchester could give.

“In August 1988 (five months before the Winchester murder) counsel for the accused received copies of the prosecution brief. Winchester was not mentioned in the brief.

“Further, as the Coroner noted, ‘it is clear that at least some of the defendants in that case had either summonsed or about to summons Winchester to give evidence on their behalf to establish a defence that they had been acting under police instructions when they were involved with the Bungendore crops’.

“It has also been suggested that Winchester was murdered as a warning to others or because he intended discussing corrupt police activity in Bungendore 1 and 2.

“These theories, as with the rest, are speculation and there is no supporting evidence.

“Any possible motive on behalf of the Italian community is extremely tenuous.”

WERE PROFESSIONAL MAFIA HITMEN USED?

The McKenzie report also examined a popular theory that two Calabrian mafia hitmen had been flown out from Italy to murder Mr Winchester.

It was established that two Calabrian mafia mobsters did indeed fly out together from Italy to Australia two months before the Winchester murder and they were met at Melbourne Airport by some members of the Bungendore 11.

One of the men later married the daughter of one of South Australia’s most senior Calabrian mafia bosses and the other was with members of the Bungendore 11 in Canberra on the night of the Winchester murder.

But the McKenzie review report said there was nothing to link either man to the Winchester murder.

There has been speculation over the years that Mr Winchester must have been murdered by an experienced killer because the hit was done so professionally, which added weight to the “mafia did it” theory.

The McKenzie report refutes that, saying proponents of this theory relied on the facts:

— THERE was virtually no physical evidence located at the Winchester murder scene.

— THAT there were no witnesses to the murder.

— THAT a silencer was used.

— THAT two shots to the head indicated a professional hit.

The report then listed the reasons those four facts don’t support the professional hit theory.

“Due to the nature of the murder very little physical evidence would be expected to be located,” it said.

“It is most probable that the murderer walked up behind Winchester, shot him twice in the head and then walked or ran off.

“Under these circumstances very little evidence could be expected.

“There was no apparent contact between the offender and the deceased or anything else at the scene.

“Two spent cartridges were located at the scene.

“It could well be argued that a ‘professional killer’ would retrieve the shells. The shells eventually led detectives to the murder weapon.

“Assistant commissioner Winchester was shot in full view of Lawley St and the houses opposite. The fact that no one saw the incident was more good luck than good management.

“That two shots to the head indicated a ‘professional hit’, the review team is unaware of any research in this regard but is cognisant of numerous murders where a deceased was shot in the head in circumstances that could not be classified as a ‘professional hit’. It does not take any special skills or experience to shoot someone in the back of the head.

“That a silencer was used, silencers were freely available during 1988/89 in the ACT and it is reasonable to expect any person who intended to shoot someone in a residential area would want the sound reduced.

“The ammunition used to kill Winchester was of the supersonic type. Use of this ammunition severely reduces the effectiveness of a silencer.

“Subsonic ammunition is far more effective and it is reasonable to expect that a ‘professional assassin’ would be aware of this fact.

“The review is satisfied that the murder weapon was purchased from Queanbeyan resident Mr Klarenbeek on January 1, 1989, after he advertised it in the Canberra Times.

“Purchasing a weapon locally and such a short time before the assassination does not have the hallmarks of a ‘professional killer’.

“There is no conclusive evidence to support the ‘professional hit theory’.

“On balance the review team believes the evidence indicates that the murder was not committed by a professional hitman.”

Yet more suggestions of Calabrian mafia involvement in the Winchester murder emerged during the 2014 judicial review of the case.

They related to the fact that roadblocks were set up around Canberra soon after the 9.15pm murder of Mr Winchester and that two members of one of the most notorious Calabrian mafia families in Australia were stopped at the same roadblock about 45 minutes apart in Canberra Ave in the suburb of HMAS Harman about 6am and 6.45am the morning after the murder.

One of the men was driving a white Holden V8 and the other was driving a blue Ford V8.

Three people living near where Mr Winchester was murdered told police that around the time he was shot they heard a loud vehicle being driven near their homes, with two of the witnesses describing the vehicle they heard as being a V8 and one of them saying he heard two gun shots then the sound of a car powered by a V8 engine being driven off “under power”.

Both men were investigated as suspects in the Winchester murder, but no evidence linking them to the murder was found.

One of them — the son of a now dead very prominent Calabrian mafia boss — was later charged with drug offences, we will call him Mr Y because his name has been suppressed by the ACT Supreme court.

Some of the evidence against Mr Y came from his house and phone being bugged by the AFP.

In one secretly taped conversation he said during a chat with another man that “the bad thing is that they found similar type bullets in my house”.

A lawyer acting for David Eastman — the man who was last month acquitted of murdering Mr Winchester — questioned former AFP Commander Ric Ninness in court about that bugged conversation, suggesting it related to the bullets used in the Winchester murder.

Mr Ninness, the officer in charge of the Winchester murder investigation, confirmed Mr Y’s house was raided in relation to the drug charges but that no bullets were found during the search.

“It was a tactic of ours to try to lock some of the Calabrians up and then see if we could do deals with them to get information about the Winchester murder,” Mr Ninness told the Herald Sun yesterday.

“Mr Y was the first bloke we banged up in August 1989. We put surveillance on him, found he was dealing heroin so we bowled him and his girlfriend over and charged him.

“I went down to the cells and offered him a deal that I would make representations on his behalf to the Director of Public Prosecutions if he came forward with information about the Winchester murder.

“I told him that provided he wasn’t the shooter it was possible we could do a deal with him over the drug charges. I told him he was looking at five or six years in jail over the drug charges, but that we would put a good word in for him with the DPP to do a deal over those charges if he provided information about the Winchester murder.

“He was sh--ing himself and I believe would have told us if he knew anything, but he gave us nothing.

“Eastman’s defence team put a great deal of credence in Mr Y’s comment about bullets similar to the ones used in the Winchester murder being found in his house.

“If we had found bullets in the house we would have been all over it like a rash, that was the sort of thing we were looking for. Remembering this was well before Eastman was charged.

“But we found nothing connecting Mr Y back to the Winchester crime and nothing implicating him ever came up over the intercepts or the listening device we had in his house.

“In fact, despite a long and extensive investigation into the possibility of the Calabrian mafia being involved in the Winchester murder, we never found anything implicating any members of it having organised or committed the murder.”

Mr Ninness also spoke to Mr Y’s father — whose name has also been suppressed by the ACT Supreme Court — who at the time was a major Mafioso in fear of his life after a falling out with other mobsters.

“I offered to relocate him overseas with a new identity so he could start a new life if he provided me with information about the Winchester murder,” Mr Ninness said yesterday.

“Like his son, I believe he would have told me if he knew anything. He said he had really good information about other crimes, but not the Winchester murder.

“I told him the only way I could get him a deal was if he provided details about the Winchester murder and that I would get the next plane back to see him if he contacted me to say he was prepared to do that.

“I assessed Mr Y’s father as being a man who was in total fear of his life at the time I spoke to him. He agreed with me at the time we spoke that he was living on borrowed time.

“He cried throughout a lengthy interview and I firmly believe that had he been able to assist us with the murder investigation he knew that it would have been in his best interests to provide us with information as we could protect him and get him a new identity.

“He was a dead man walking at the time and if he knew who killed Mr Winchester I believe he would have told me.”

The Federal Court’s 1997 decision rejecting Mr Eastman’s appeal against his conviction mentioned three police intelligence reports Mr Eastman had attempted to use to support his argument that the Calabrian mafia murdered Mr Winchester.

Those documents remain suppressed and are referred to in court and other documents as MFI 23, 97 and 130.

The Federal Court decision said MFI 23 identified a Calabrian man who police believed might have murdered Mr Winchester based on secretly taped conversations in which he talked about shooting somebody in the head.

But the decision said a later report, MFI 97, found the man’s Calabrian dialect had confused the interpreter and that the man’s conversations had been interpreted incorrectly in MFI 23 — the man’s comments were of a sexual nature made while in bed with his partner and had nothing to do with shooting anybody.

“When MFI 23 and MFI 97 are read together, they show, contrary to the theme of the defence case, that lines of inquiry unrelated to the appellant (Mr Eastman) had been the subject of very extensive police investigation, and had failed to produce evidence suggesting the murder had been committed by the people (Calabrian mafia members) or organisation (who were) the subject of the investigation.”

The final part of this three part series on the Colin Winchester murder will be published at heraldsun.com.au tomorrow and will examine the other suspects.