Withheld evidence may prove who committed shooting murder of AFP top cop Colin Winchester

It is 30 years since the most senior police officer ever murdered in Australia was gunned down outside his Canberra home. The man charged over his murder was acquitted last month — but senior police believe this withheld evidence would have seen a different result.

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It is 30 years since the most senior police officer ever murdered in Australia was gunned down outside his Canberra home.

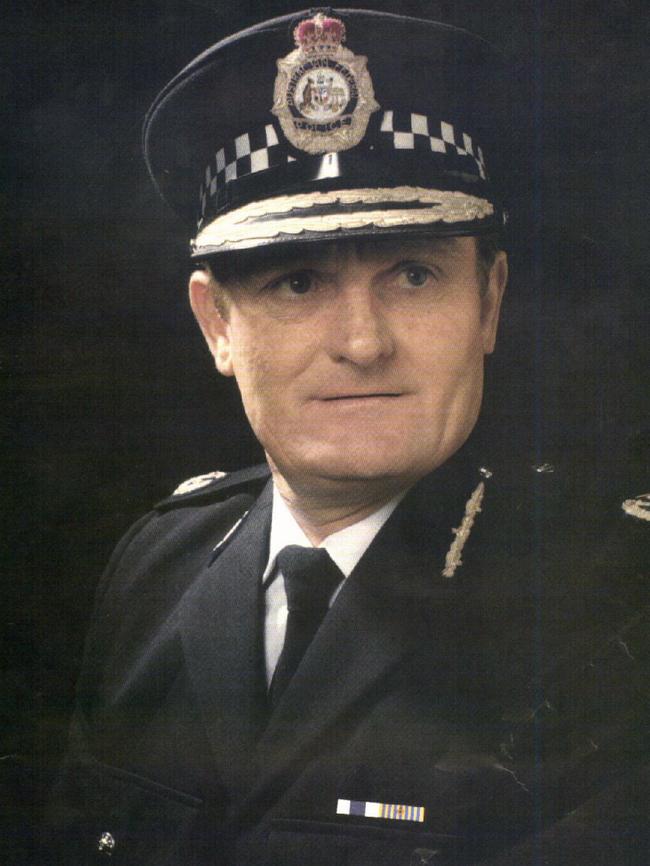

The January 10, 1989, assassination of Australian Federal Police assistant commissioner Colin Winchester was huge news at the time.

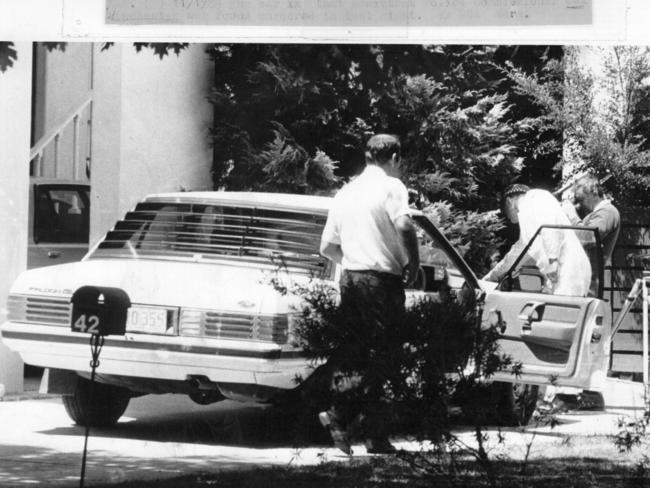

He probably never knew what hit him as he prepared to climb out from behind the wheel of his cream Ford Falcon about 9.15pm.

SHADES OF LAWYER X SCANDAL IN COP MURDER CASE

He had just driven his unmarked police car into the driveway next door to his Lawley Street home in the Canberra suburb of Deakin. He had an arrangement with his elderly widowed neighbour to give her some security by leaving his car in her driveway overnight.

The waiting assassin had the cover of darkness, as well as shelter provided by Deakin’s many tall gums and shrubs. He watched Mr Winchester’s car slow down and stop before creeping up from behind.

Bringing his .22 Ruger rifle to his shoulder, he waited for the top cop and father of two to open the car door and start getting out before making his move.

The first shot was fired into the back of Mr Winchester’s head from a distance of between 400mm and 600mm, meaning the muzzle of the weapon was in the vicinity of the centre door pillar when the trigger was pulled.

To make sure of death, a second shot was pumped into 55-year-old Mr Winchester’s brain through the side of his head, just above the right ear. An autopsy later revealed either shot would have been fatal.

The killer operated swiftly, departing the murder scene without being spotted and before Mr Winchester’s wife Gwen, who was inside the house, discovered her husband’s plight.

He also operated efficiently, leaving nothing of himself behind that might later identify him. With modern-day DNA techniques, that is no mean feat. Two shell cases were later found and unsuccessfully tested for fingerprints. The Ruger 10/12 self-loading rifle used in the shooting is still missing.

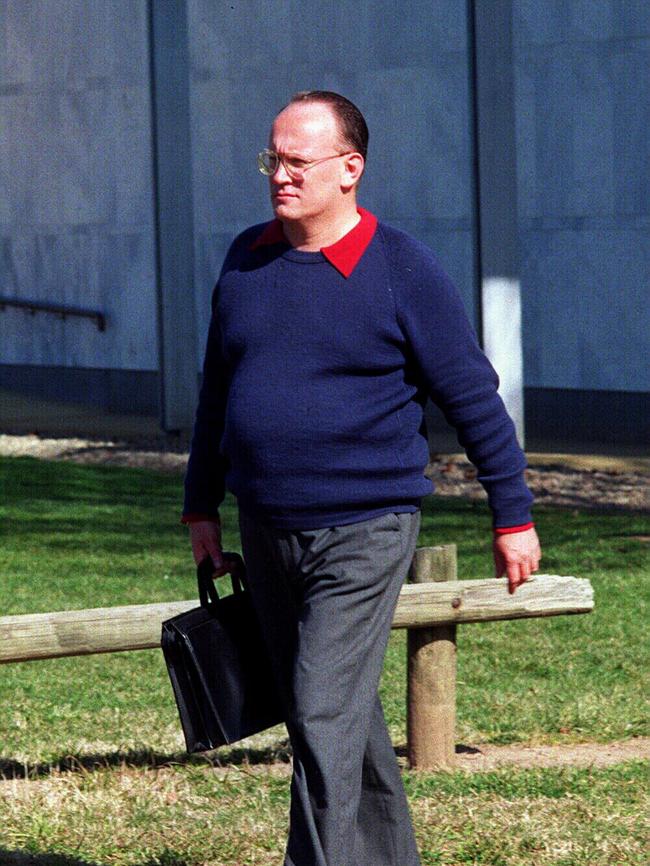

The Winchester murder was huge news again in December last year when David Harold Eastman — the man charged and later convicted in 1995 of murdering Mr Winchester — was acquitted at his retrial after spending 19 years behind bars.

The not guilty verdict in the ACT Supreme Court came after a six-month trial, during which jury members heard from 127 witnesses and had statements read out from 41 others.

Mr Eastman, now aged 73, was released in 2014 after a judicial inquiry found the original guilty verdict was based on “deeply flawed forensic evidence”.

The man who ran that judicial inquiry, acting Justice Brian Martin, didn’t exonerate Mr Eastman though.

“I am fairly certain that the applicant (Mr Eastman) is guilty of the murder of the deceased, but a nagging doubt remains,” acting Justice Martin said.

That nagging doubt led to acting Justice Martin finding Mr Eastman’s sentence of life in jail without parole was a “substantial miscarriage of justice” that warranted his 1995 murder conviction being quashed.

Acting Justice Martin was firm in his finding that there shouldn’t be a retrial.

“In my view, the passing of so many years, coupled with the death of numerous witnesses and publicity prejudicial to the applicant, mean that a further trial would be unfair both to the prosecution and to the applicant,” he said in his final report.

“A retrial would not be in the best interests of the community.”

Despite Acting Justice Martin’s advice, the ACT Director of Public Prosecutions went ahead with the retrial anyway, resulting in last month’s acquittal of Mr Eastman.

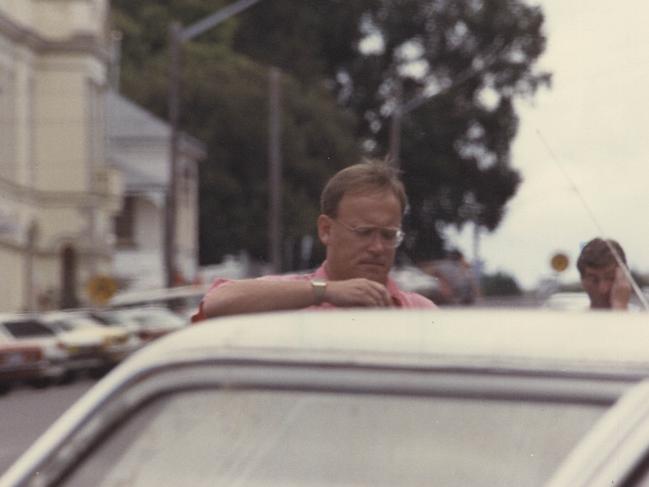

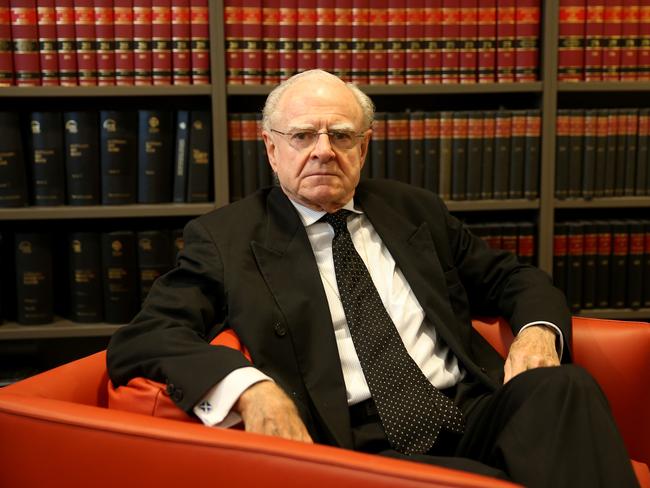

Former AFP Commander Ric Ninness, the man who led the Winchester murder investigation, doesn’t have any nagging doubts that he charged the right man.

In his first interview since Mr Eastman was acquitted last month, Mr Ninness recently told the Herald Sun he fully expected the second trial would come up with the same guilty verdict the first jury handed down — and was stunned when it didn’t.

“I was numb, devastated. That’s 30 years of my life down the drain,” Mr Ninness said.

“I am still totally perplexed at the reasons for the acquittal,” Mr Ninness said.

“Never in my wildest dreams did I believe he would be acquitted.

“There are just too many connecting factors to link Eastman to the crime.

“I feel terrible about the acquittal, but there’s nothing I can do about it. That’s the system we live under.

“The judge I thought was very good. He gave a very good definition — that I thought a school student could have followed, let along adult jury members — of how circumstantial evidence can be relied on in a prosecution.”

The reason the judge gave directions to the jury about how they should treat circumstantial evidence was the case against Mr Eastman was an entirely circumstantial one.

There were no witnesses to the murder, the murder weapon has never been found and Mr Eastman maintained his innocence throughout both trials.

But Mr Ninness’s view is there were more than enough separate strands of circumstantial evidence to warrant charging Mr Eastman with murdering Mr Winchester — and for him to be convicted of it.

He said he was also in possession of what he considered to be a damning piece of evidence implicating Mr Eastman in the Winchester murder that jury members never got to hear.

They never got to hear it because it came from one of the many lawyers Mr Eastman hired and fired and it was ruled inadmissable due to it being covered by client/lawyer privilege.

Long before Mr Eastman was charged over the Winchester murder, police secretly taped the lawyer after he asked to see them to report his fear that Mr Eastman was planning to harm him or his family.

“They had a fallout and the lawyer refused to continue acting for Eastman,” Mr Ninness said yesterday.

“The lawyer and his family were at the Canberra Airport on one Saturday afternoon, travelling interstate, and David Eastman approached him and made a veiled threat to his safety.

“The way Eastman spoke and looked at the lawyer’s young daughter that day sent shivers through the lawyer’s spine and scared him to the extent he rang Tom McQuillen, one of my detective sergeants, and asked for a meeting with me and Tom.

“So we met with him at the city police station and he then told us he was in fear of Eastman and in fact he had put security measures in place at his private home.

“He told us that if something happened to him there was evidence in his law partner’s safe at the legal firm that would convict Eastman and that in the event of him coming to harm he had left instructions with his firm to release the contents of the safe to us.

“The lawyer also said, in an evasive and roundabout way, that he believed Eastman had thrown the gun used to kill Mr Winchester in a river or waterway in and around Canberra. That murder weapon has never been found.

“The lawyer said Eastman had owned a number of firearms and that he could account for the whereabouts of most of them, but there was one that couldn’t be accounted for. I took that as the lawyer indicating to us the weapon that couldn’t be accounted for, and which Eastman owned, was the murder weapon.

“He even stated he was prepared to work with us and try to set Eastman up. But he said it would be the end of his career if he gave evidence against Eastman, which I appreciated. I told him I realised he could never give evidence about what he was telling us.

“I told him I couldn’t imagine a set of circumstances where he would be forced to give evidence against Eastman because of the confidentiality clause between solicitors and clients.

“Having said that, he was prepared to steer us in the right direction with certain things about Eastman that could help with our investigation, sometimes in the form of hints and other times more directly.

“He certainly wasn’t aware we were secretly taping him. He would never have been so forthcoming with what he told us if he had known that.”

Mr Ninness said no harm did ever come to the lawyer or his family so police never found out what the supposed damning evidence against Mr Eastman was that the lawyer claimed would be enough to get Mr Eastman convicted of murdering Mr Winchester.

He said he did try to make the lawyer disclose what he knew during Mr Eastman’s trial, but it was ruled inadmissable so the jury never got to hear about it.

The only reference made to it was by the then prosecutor, Jennifer Woodward, who described the secret and inadmissable evidence as “devastatingly prejudicial” against Mr Eastman.

Mr Ninness said he was convinced the lawyer was telling the truth about what Mr Eastman had told him and that he did have evidence locked away in a safe that would implicate Mr Eastman in the Winchester murder.

“I have no doubt about that. He was a man in fear at the time he approached us to talk about Eastman,” Mr Ninness said.

“What he said was the evidence that would convict Eastman was in the safe and that if anything happened to him or his family we should go and get what was in the safe.

“He has never revealed what it was that was in the safe and since coming to us for protection from Eastman he has become very guarded in dealings with me.

“Years later somebody told him I was writing a book and he made an approach to me to say he was concerned for his reputation and his legal career in the event I went public with the information he provided to us.

“He was worried about being identified as a lawyer who provided information to police about a client.

“Prior to the second trial starting they had quite a number of closed court sessions and the information the lawyer provided to us was one of the topics raised.

“I believe the judge ruled it was solicitor/client privilege and ruled not admissible so the jury never got to hear about it.

“In hindsight, I am kicking myself that after the lawyer told us about the evidence that was in his safe that he claimed would convict Eastman that I didn’t try to get a court order to seize the safe so I could examine its contents.

“Doing so would have been very controversial and the legal fraternity would have been up in arms about police breaching solicitor/client privilege if I succeeded in getting a search warrant, but the uproar would have been worth it because, gee, to this day, I think constantly about what might have been in that safe.”

That secretly taped discussion with Mr Eastman’s former lawyer came well before Mr Ninness charged Mr Eastman in 1992 with the 1989 Winchester murder.

It, along with information from the wife of the man who sold the murder weapon used to shoot Mr Winchester, convinced Mr Ninness to continue ploughing resources into investigating Mr Eastman.

Mr Eastman was kept under constant surveillance from January 13, 1989, three days after the murder, to August 7, 1990 and for several periods in 1992. His home was bugged and police transcribed thousands of hours of Mr Eastman talking to himself.

One of the weaknesses in the prosecution case was the murder weapon has never been found.

But police were able to prove beyond doubt that the gun used to shoot Mr Winchester twice in the head was a Ruger 10/22 rifle sold by Queanbeyan gun dealer Louis Klarenbeek on January 1, 1989, just nine days before the Winchester murder.

Detectives were disappointed after Mr Klarenbeek was shown a group of photographs on January 28, 1989, including one of Mr Eastman, and did not identify anyone from the photographs as the buyer of the Ruger.

Mr Ninness said it wasn’t until after Mr Klarenbeek died that his wife Joanna claimed to police that her husband had lied to police when he said he hadn’t sold the murder weapon to Mr Eastman.

She claimed he told her it was Mr Eastman who bought the Ruger, but that he had also told her he wasn’t going to admit that to police and that she shouldn’t either.

“Mr Klarenbeek was initially treated very poorly by the detectives during the inquiry and he had his back up and I can understand why,” Mr Ninness said.

“We are trying to nurture him as a witness, yet he is locked up for admitting he sold a weapon illegally he shouldn’t have sold.

“That was his hobby. He would go to gun shops and buy a gun and clean it up and put an ad in the Canberra Times to sell, it was his pocket money.

“He was badly treated and when he wouldn’t identify Eastman from the photographs we also showed him photographs of the other people we tracked down who we knew Klarenbeek had sold guns to and he picked none of those out either.

“So it wasn’t just Eastman he refused to identify, he refused to identify any of them.

“After he died his wife appeared before the Coroner’s Court to give evidence at the inquest and she was talking to the interpreter, a policeman who spoke her language, and she told him that in fact her husband had confided to her that Eastman did come to the house and did purchase the Ruger.

“She said her husband told her he wouldn’t tell the police because of the fear for his safety and her safety.

“At that stage he knew he was dying of cancer and his wife would be on her own and he was terrified Eastman would come after her.”

Mr Ninness said two more strands of evidence against Mr Eastman from another one of his lawyers and one of his doctors also helped convince him to charge Mr Eastman with the murder of Mr Winchester.

“On September 7, 1989, I received information that a solicitor by the name of Dennis Mario Barbara had been involved in a conversation with Eastman in late 1988,” Mr Ninness said yesterday.

“Mr Barbara was representing Eastman at the time in relation to an assault charge laid against Eastman and during the conversation Mr Barbara claimed Eastman said ‘I will kill Winchester and get the Ombudsman too’.

“I investigated that and discovered Mr Barbara had told barrister John Burns what Eastman had said about Mr Winchester and the Ombudsman and that Mr Burns later passed the information to police.

Det-Sgt McQuillen and I made an approach to Mr Barbara but he refused to make a statement, saying that at the time Eastman was a client of his and, that meant the conversation was subject to legal professional privilege.

“Mr Barbara told me that he had discussed this matter with his partner, Jack Pappas, and his advice from Mr Pappas was that this matter was professional legal privilege and that he would not be coming forward to divulge this information.”

This is what Mr Barbara told Mr Ninness on September 7, 1989.

NINNESS: “During the conversation that you had with Mr Eastman, did he state that he intended to kill Mr Winchester?”

BARBARA: “I am going to claim privilege on that.”

NINNESS: “Can you tell me, on the basis of that conversation, if he mentioned Mr Winchester in the threat?”

BARBARA: “Yes, you are on the right track, it was while we were discussing the matter of the assault, and he became quite heated and agitated, and made the threat.”

NINNESS: “Can you remember the exact words that were used?

BARBARA: “Yes, its unequivocal the words he used. He was speaking about the Ombudsman and the police complaints in the coming assault matter. It was during this conversation that he got agitated and made the direct threat against Mr Winchester.”

Mr Ninness yesterday said Mr Barbara was later issued with a subpoena to give evidence at the Winchester inquest and during his evidence he said Eastman had consulted him about the assault charge, his complaints about police handling of the matter and his dealings with the Ombudsman.

“He said he saw Eastman in late October 1988 and again in late November or early December, 1988, just weeks before Mr Winchester was murdered,” Mr Ninness said.

“Mr Barbara gave evidence that on the second occasion Eastman became upset and said ‘I will kill Winchester and I will get the Ombudsman too’.

“He told the inquest he was 99 per cent certain those were the exact words Eastman used and that he had no doubt Eastman used Mr Winchester’s name and that the word kill was used in relation to Mr Winchester.

“Mr Barbara further stated in his evidence that Mr Eastman said the words in the course of a short emotional tirade, saying ‘it was a short moment of passion’ during which Mr Eastman seemed frustrated.”

Four days before Mr Winchester was murdered, Mr Eastman visited his medical practitioner, Dr Dennis Roantree, who had treated Mr Eastman for 10 years for a range of ailments, including psychiatric illnesses and paranoia.

Dr Roantree later gave evidence in court that Mr Eastman told him about a recent meeting he had had with Mr Winchester and that Eastman had been furious when talking about Mr Winchester.

He said he wrote in Mr Eastman’s medical notes at the time that as he was leaving Eastman said “I should shoot the bastard”.

Dr Roantree later put a pencil line through that statement in Mr Eastman’s medical file.

When questioned about this in court, Dr Roantree said he had told police he was not prepared to swear that was what Eastman said, but acknowledged “that had I not recalled that accurately, I wouldn’t have ever mentioned it”.

It was just three days after the Winchester murder that Dr Roantree contacted Mr Ninness to tell him of his suspicion Mr Eastman might have done it.

Dr Roantree said during that January 13, 1989, interview with Mr Ninness that Mr Eastman had spoken about his recent meeting with Mr Winchester and that Mr Eastman said that during it he was so angry he felt like pushing Mr Winchester off his chair and that as Mr Eastman was leaving the surgery he said something to the effect of “the police should be taught a lesson and I should shoot the bastard”.

Asked if after the murder it was likely Mr Eastman would have thought “Winchester is dead now and I remember telling the doctor last week that I’d like to kill him”, Dr Roantree replied: “I’d be surprised if he hadn’t thought of that. That’s why I’ve been worried because he’s, he’s a smart cookie.”

NINNESS: “In light of this we better have your home under some protection until we can get this sorted out.”

ROANTREE: “Although my assessment of him would be that he would have done that and I don’t think that he’d do anything else, I haven’t been too worried but it has crossed my mind.”

NINNESS: “If he’s got to cover his tracks there’s a possibility he wouldn’t stop at one.”

ROANTREE: “I’ve been checking my garden very closely before parking.”

NINNESS: “Do you think he’s capable of murder now?”

ROANTREE: “Oh yeah, yeah he’s capable.”

Mr Ninness said he believed the fact Mr Barbara and Dr Roantree reported Mr Eastman using similar phrases in relation to harming Mr Winchester was strong circumstantial evidence.

“Yes, Dr Roantree put a pencil line through the words relating to shooting Mr Winchester, which meant the jury never got to hear that bit of evidence — but the words were still clearly visible in his notes,” Mr Ninness said yesterday.

“If he had been a policeman he would have been directed to give that evidence in court.

“It would have had to come out. He couldn’t just say ‘I made a mistake and put a line through it’. The court would make you stick with that original comment.”

Mr Ninness said the case against Mr Eastman was certainly weakened by the discovery between the first and second trial that crucial forensic evidence was flawed.

That evidence, presented to the jury members in the first trial, who found him guilty, related to gunshot residue.

They were told gunshot residue was found inside Mr Eastman’s blue Mazda 626 — on the driver’s side door handle, on top of the indicator switch and on top of the rear vision mirror — and that partially burnt propellant was discovered in the boot.

The evidence given by a since disgraced forensic scientist, whose name is suppressed, was that the residue and propellant found in Mr Eastman’s car were both from the type of PMC brand ammunition used to kill Mr Winchester.

That first jury was also told the partially burnt propellant found in Mr Eastman’s boot matched propellant found at the murder scene and that both lots of propellant were manufactured at the same time.

The 2014 judicial inquiry conducted by acting Justice Brian Martin found there were serious flaws in the forensic evidence, which led to it not being presented to the second jury, which last month found Mr Eastman not guilty.

Doubt was also cast during the judicial inquiry on various conversations police secretly taped of Mr Eastman talking to himself in his home, with disputes between experts as to the content on what was said on the very poor quality recordings.

As an example, the police interpretation of one of the recordings was that Mr Eastman said: “He was the first man I ever killed. It was a beautiful thing. One of the most beautiful feelings you’ve ever known.” Whereas another expert thought Mr Eastman said “kissed” not “killed”.

Mr Ninness and the ACT Director of Public Prosecutions claimed that even leaving out the questionable forensic evidence and the disputed bugged conversations the case against Mr Eastman was still overwhelming, although the jury members who acquitted thought otherwise.

The various strands of evidence in the case against Mr Eastman included:

— HE had a motive to murder Mr Winchester because he was desperate to get back into the public service but was unlikely to succeed because of an outstanding charge that he assaulted his neighbour, Andrew Russo. During a meeting with Mr Winchester on December 16, 1988, arranged by the then shadow attorney-general Neil Brown, QC, Mr Eastman failed in his attempt to persuade Mr Winchester to drop the assault charge. Mr Brown later told police Mr Eastman had become very angry during the meeting and told Mr Winchester “if your hoons think they can treat me like this they’ve got another thing coming”. Mr Brown revealed Mr Eastman was so incensed he refused to shake Mr Winchester’s hand as the stormy meeting drew to a close. Mr Winchester wrote in his police diary that day: “RE Eastman: Belligerent manner.”

— MR Eastman was given a letter from Mr Winchester on December 20, 1988, in which Mr Winchester confirmed he was refusing Mr Eastman’s request that he intervene in the assault case. Mr Eastman then persuaded Mr Brown to go over Mr Winchester’s head and write a letter of complaint to the then AFP Commissioner, Peter McCauley. Commissioner McCauley replied directly to Mr Eastman in a letter which supported Mr Winchester’s view that the AFP wasn’t going to agree to Mr Eastman’s request to intervene in the assault case. That letter was delivered to Mr Eastman on the morning of the day Mr Winchester was murdered.

—THE charge of assaulting Russo led to Mr Eastman having an intense hatred of police. Public servant Ronald Ostrowski gave evidence that Mr Eastman expressed great animosity towards police for both charging him with the Russo assault and for later failing to drop the charges. Mr Eastman claimed he was being victimised by police, was being unfairly treated and accused police of acting corruptly against him.

— MR EASTMAN was searching for a gun in the months leading up to the murder. Telephone records revealed Eastman rang a number of gun sellers who were advertising weapons in the pages of the Canberra Times and police have further evidence of him having inspected guns at the homes of sellers.

— A COUPLE of days before Mr Winchester was murdered, Mr Eastman met a police inspector by chance outside the building where Mr Winchester worked. Pointing in the direction of Mr Winchester’s office Mr Eastman said: “The executive in this building is corrupt and has a lot to answer for.”

— MR EASTMAN’S failure to recall where he was on the night of the murder. When he was questioned by police the day after the murder he was unable to remember specifics of where he was or what he was doing, on the night of the murder, simply saying he had just driven around. In a submission to the Martin judicial inquiry the ACT DPP said: “The Crown case as to this matter was that Mr Eastman did not wish to commit himself to an account of where he was that night since he surmised that he may well have been observed. The clear inference to be drawn was that someone with Mr Eastman’s intelligence and memory skills would be able to recall where they were the previous evening, and that if he declined to advise police of his movements it could only be because he had something to hide.” The Federal Court cast doubt on Mr Eastman’s claim he couldn’t remember where he was or what he did on the night of the Winchester murder. Its 1997 ruling on Mr Eastman’s failed appeal against his conviction said: “The appellant (Mr Eastman) is a highly intelligent man. That is apparent from many aspects of his evidence and conduct at trial. A perusal of the transcript of the trial also shows that he was a very competent cross-examiner, possessed of an excellent memory. It was open to the jury to conclude, as the Crown argued, that it was wholly inconsistent with his personality, character and ability that he was unable to recall his movements in the preceding evening.”

— INITIAL denials by Mr Eastman that he had purchased a gun. The DPP submission to the Martin inquiry said: “It was also the Crown case that Mr Eastman decided to admit to searching for and buying guns not because he wanted to be frank but because it was finally brought home to him that any denial simply could not be believed.”

—MR Eastman wrote a letter to a female friend just 16 days before Mr Winchester was murdered. In it Mr Eastman complained about being charged with assaulting his neighbour and said: “Now I want to kill the neighbour, his friends, and the bastard police as well. I have been to a solicitor. Of course, he doesn’t care except that this is a chance to make some more money. I sympathise with men who kill hundreds, thousands, millions. Now you know the truth.”

— DURING January, June, October and November of 1988, Mr Eastman responded to advertisements for the sale of firearms, including Ruger .22 rifles, which was the type of weapon used in the Winchester murder. Mr Eastman claimed he was looking for a weapon because of his fear of the neighbour he was charged with assaulting. Evidence was given that while Mr Eastman did complain to various people about the neighbour he never expressed being in fear of the neighbour.

— ON January 10, 1989, the morning of the night Mr Winchester was shot dead as he was getting out of his police car outside his house, Mr Eastman was seen in a car park adjacent to the police building looking into the rear of police vehicles.

— BETWEEN May and December 1988 Mr Eastman attended at the electoral office on more than one occasion and asked to look at the supplementary electoral roll. Mr Winchester’s name and address appeared on the supplementary roll on March 2, 1988 and remained on the supplementary roll until October 2, 1988, when they were placed on the official role.

— ON January 8, 1989, two days before Mr Winchester was murdered, a witness saw a car parked outside the house next door to Mr Winchester’s home in Lawley St, Deakin, about 9.20pm. Mr Winchester was in the habit of parking his car in his next door neighbour’s driveway as she lived alone and felt having the car parked there provided added security for her. He had just parked in the neighbour’s driveway when he was shot dead. The witness who saw the car parked there two days before the murder said as she walked past the car the driver moved to position himself so that he would not be seen by her. She didn’t take a note of the car’s registration number, but after the Winchester murder she described the vehicle to police as being an aqua or turquoise Japanese type vehicle similar to a Datsun or a Mazda and that from memory she though the registration number was YPQ 038. Mr Eastman’s car at the time was an aqua blue Mazda 626 and its registration number was YMP 028, very close to the number the woman provided. The witness told police she thought the driver was a male, but couldn’t describe him as she only saw the driver’s right arm, which she described as thick and hairy, resting on the car window sill. Two other witnesses told police they saw a car similar to Mr Eastman’s parked near Mr Winchester’s house in the few days prior to the murder.

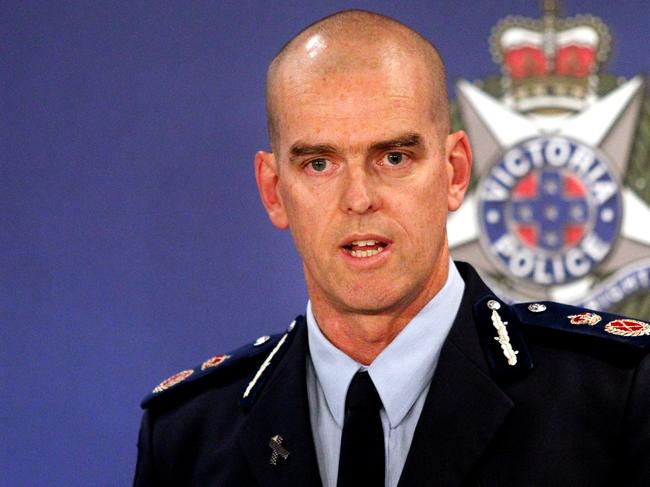

— FORMER Victoria Police Chief Commissioner Simon Overland, who at the time was working on the Winchester murder case as a member of the AFP’s major crime squad, spoke to Ms Leslie Vick, the principal legal officer for the then Senator Janine Haines, four days after the Winchester murder. Ms Vick said Mr Eastman had approached Senator Haines in March 1988 to try to persuade her to help him get his assault charge dropped so he could get his public service job back. She claimed he made threats to kill people and that he was contemplating “blowing someone’s head off”. Ms Vick told Mr Overland the threats made by Mr Eastman to kill people came after it became apparent to Mr Eastman that the efforts being made on his behalf by Senator Haines and her staff in relation to the assault proceedings were proving unsuccessful. Ms Vick claimed that during a phone conversation with Mr Eastman he told her “I’ll probably have to kill someone to get the attention paid to the injustice that’s been done to me.”

— POLICE interviewed Scott Thompson in relation to a Ruger 10/22 rifle he had advertised for sale in the Canberra Times for $250. He told police a man he identified as Mr Eastman came to his home on September 9, 1988 and inspected the rifle before leaving, saying it was too expensive. Mr Thompsons told police that during negotiations with the man he believed was Mr Eastman the man suggested meeting in Queanbeyan in New South Wales, just outside the ACT, to complete the sale. He got the impression the man didn’t want to buy the weapon in his real name and didn’t want to buy it in the ACT because of the stricter legal requirements for the sale of firearms in the ACT.

— GUN seller James Lenaghan told police a man he identified as Mr Eastman bought a Ruger 10/22 rifle from him on February 13, 1988 for $200. A police check on Mr Eastman’s banking records revealed he drew $200 out of an ATM that day. That rifle was found by a member of the public hidden in a storm water culvert on a section of the disused Old Federal Highway in May 1988.

— POLICE seized documents belonging to Mr Eastman which listed a number of prostitutes he had visited. Police tracked down and spoke to these prostitutes. One of them said she had seen a man she believed was Mr Eastman between six and 12 times at the Canberra brothel called Sasha’s. During the visits he talked about shooting and his interest in firearms, as well as saying he enjoyed travelling to Europe and had an interest in ornithology and Aboriginal artefacts. Mr Eastman had travelled extensively in Europe, was a member of the Canberra Ornithological Group and was interested in Aboriginal artefacts. Another prostitute told police Mr Eastman was a regular client and that the last time she saw him was at the Studio 3 brothel about three to four months before the Winchester murder. She said he talked to her about not liking police and his interest in shooting. She said he offered to show her his firearms if she would go on an escort visit to his home. She told police she refused because she was in fear of him.

— THE then senior assistant Canberra Ombudsman, Hugh Selby, told police he had regular dealings with Mr Eastman over complaints Mr Eastman made to the Ombudsman’s office about his dealings with police and complaints he made against members of various Commonwealth agencies. On one occasion Mr Eastman confronted Mr Selby at a Canberra seminar. “Eastman and I then had a short conversation in which he wanted to know what I was doing about his complaints,” Mr Selby told police in a sworn statement. “I told him that, as he had already been informed in letters, that we, the Ombudsman’s office, were not doing any more about them. He then threw his plastic cup of white wine over me and grabbed me with one hand at the top of my tie at my neck and pulled me about five metres out of the door and up the corridor. He then just let go and then ran off up the corridor. In my dealings with Eastman, I believe he was a man of high intelligence at one stage had a bright future in the public service. He did, however, have a volatile temperament and an obsessive nature. By obsessive, I mean that in my dealings with him he wouldn’t accept an answer that was contrary to the one that he wanted.”

— MR EASTMAN’s mother told police in 1987 she had received threatening phone calls from her son in which he made threats to murder her and his father. A keep the peace order was taken out by Mr Eastman’s mother in which he was ordered to stay away from his parents and other family members. Mrs Eastman told police her son was psychopathic and that she had been having trouble from him for a number of years.

— A FORMER public servant gave evidence that Mr Eastman contacted him to discuss separate complaints they had both made to various agencies. He claimed Mr Eastman said: “Well, sometimes I just get so frustrated I could just get a gun and kill someone.”

SUBSCRIBE TO LIFE AND CRIMES ON ITUNES

— Part two of the three part Winchester murder series will be online at heraldsun.com.au tomorrow and it will examine the case against the Calabrian mafia.