What led twins Peter and Doug Morgan to become the After Dark Bandit?

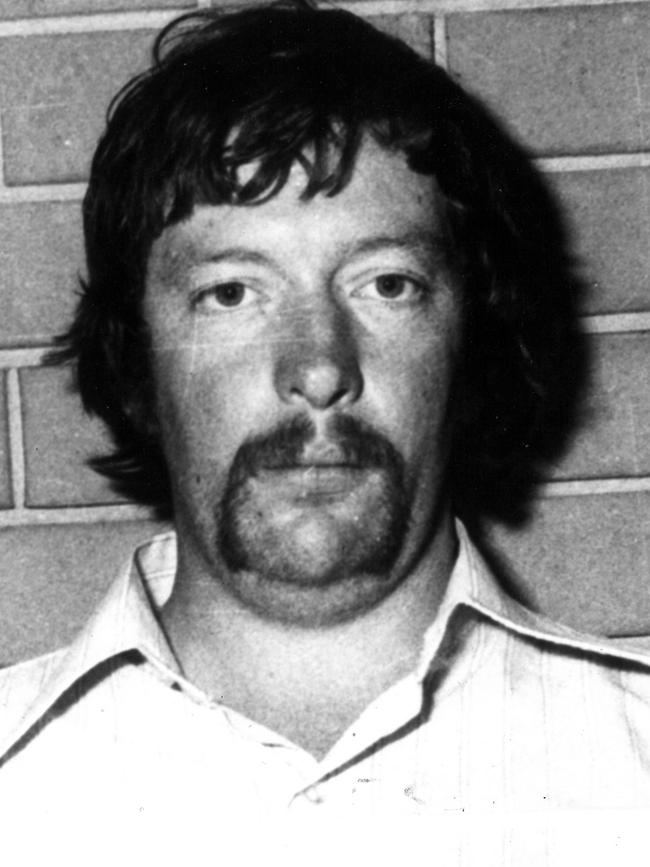

The After Dark Bandit terrorised banks and TABs for two years. Except, there wasn’t just one person playing the role. So what would lead a pair of cleanskins like the Morgan twins, both family men and talented builders, to suddenly resort to a life of crime?

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For too long, the story of the After Dark Bandit has been the greatest Australian crime story never told.

It’s the story of a daring bandit who popped up out of nowhere and terrorised banks and TABs from one side of Victoria to the other, robbing 24 of them in a two-year reign as public enemy number one.

It was only after his arrest that police discovered he was also public enemy number two — the bandit was a composite villain, with identical twin brothers Peter and Doug Morgan alternating in the role.

MASTERMIND’S DRUG DEALS AND A CODE THAT CAN’T BE CRACKED

BLOODY FAMILY TIES IN AUSTRALIA’S DARK PAST EXPOSED

COLD CASES WAITING TO BE CRACKED

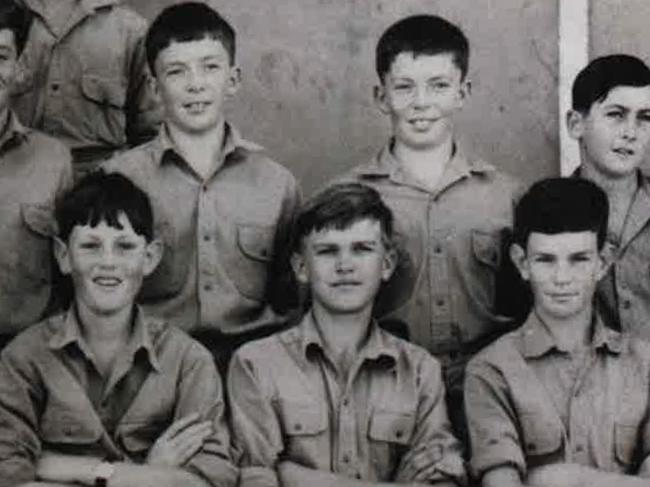

What baffled police was why a pair of cleanskins like the Morgan twins, both family men and talented builders, would suddenly, at the age of 23, resort to a life of crime, but, as authors Geoff Wilkinson and Ross Brundrett reveal in a new book Double Trouble — the amazing true story of the After Dark Bandit, the twins’ dysfunctional childhood almost predetermined their decision to break bad.

It is 40 years to the day since the After Dark Bandit shot a policeman in the back, twice, pulled his last holdup and prompted one of the biggest manhunts ever seen in central Victoria.

It was a pulsating episode in the state’s criminal history, but in some ways more intriguing was the sequence of events that led the Morgan twins to this cataclysmic moment.

The first and far-reaching incident occurred before the twins were even born. In 1949, their father, Kay Morgan, pulled out a pistol and fired twice in a botched attempt to rob the Commercial Bank at Eltham.

But rather than scare the bank staff into submission, Morgan just made them angry. In post-war Melbourne, banks armed their employees, and receiving officer Lindsay Spear and fellow bank staffer Harry Wallace returned fire … with interest.

It was later confirmed the bank pair fired 15 rounds at Morgan, just 19 at the time, who flew out of the bank in such a state of panic that he crashed his getaway car 400 metres down the road. A tip-off would lead to his arrest months later.

But three years in jail seemed to do the trick for Morgan, who married his childhood sweetheart, Beryl, on his release and set about righting the wrongs of the past.

By the time Peter and Doug arrived on the scene, at Stawell Hospital on October 30, 1953, their father was 24 and living the Baby Boomer dream.

His bank robbing days were all behind him and now he was ready, willing and able to reap the rewards of hard work and good decisions.

Those early years for the Morgan family were like building blocks. Morgan bettered his prospects with every move he made.

Soon after the birth of his boys, he left his job at the Stawell Timber Industry co-op, and within a couple of years he had left the northwest of Victoria altogether.

By the time the boys were ready for school, their dad was back in the big smoke of Melbourne, making a name for himself in the exciting new world of property development.

Morgan was one of the busiest home builders in Melbourne until hit by a credit squeeze in the early ‘60s.

“When the business went bad, Dad siphoned some money away from the business accounts … who wouldn’t?” his forever loyal son Doug would later remark.

That triggered the start of what was to become a fluctuating lifestyle for the family as the patriarch flitted between legitimate employment and nefarious activities.

The Morgan family became a nomadic clan, making the most of whatever situation they found themselves in, then moving on at a moment’s notice, sometimes in the dead of night and often with men in uniform hot on their heels. Later in court it would be claimed the boys moved house somewhere between 30-40 times.

The family first moved to Mornington where their father managed to continue building houses with a business partner (who still had a builder’s licence) but soon it was time to move again as Dad’s dodgy business dealings of the past began catching up with him.

They left Mornington in a hurry and lobbed in New Zealand, which, back in the day, didn’t require a passport if you were an Aussie.

By 1965, the boys were attending Taita Intermediate School and living in suburban Wellington, with their dad holding down a regular job until he convinced his boss he could help him buy a shiny new Australian car. The boss parted ways with 500 pounds but the new car never arrived.

Not surprisingly, Kay Morgan did not wait for his boss to report the crime to the police. Whenever the quick departure was on there was never a family discussion, just the patriarch announcing: “We are on the move again”.

By this time, Doug and Peter had already developed a love/hate relationship.

For their 10th birthdays, Dad had bought them boxing gloves; perhaps thinking that might help them settle their differences. No such luck. Doug claims to have knocked his brother over the first time they boxed and they never put those gloves on again, although they would return to the boxing ring many years later … in Pentridge.

Beryl and the boys rented a house on Auckland’s North Shore and Doug says it was here that his dad made the decision to embark on a full-time career in crime “breaking in to post offices at night, taking the old stand-up safes, wheeling them out of the building in a trolley, putting them in a car and driving off.”

It sounds anything but a criminal master plan, but using the same MO, Morgan robs post office after post office. And he is canny enough to store the safes at a second house, rented under another name … what you might call the ultimate safe house.

The “den of iniquity” as Doug called it, was situated about a 15-minute walk from where they were living, which was just close enough for a couple of inquisitive young boys to keep snooping around.

“I had my toy car set there, my toy train set.” And in between playing around, they would watch their dad empty out the safes using a hammer and cold chisel.

From the outside looking in, those awkward years of adolescence for the twins were only made more confusing as they witnessed first hand the crimes of their father.

Rather than hide his crooked ways from his sons, Kay Morgan was soon encouraging them to tag along.

To this day, Doug is unsure whether his main role was to act as a lookout or merely to act as a sort of decoy.

“Dad figured that if police pulled us over in the middle of the night, it would look less suspicious if a man had his young son in the car with him.”

So confident had his dad become, after robbing a nearby supermarket he kept a roof tile loose so he could pop back again whenever he needed cigarettes or alcohol.

But it was the post offices that were the most lucrative and Doug believed his father might have robbed as many as “30 or 40’’ post office safes.

“Basically, he was robbing every post office between Auckland and Wellington,” was Doug’s estimation.

So what effect did witnessing their father evolve into a full-time thief have on the twins? Doug dismisses the question. As far as he was concerned there was no adrenaline rush watching a safe get smashed open to reveal its treasure of cash and stamps (which they sold back to post offices). “I’d become institutionalised into a crime family by then so it wasn’t exciting as such.”

During his court hearing years later, Peter Morgan suggested that being exposed to his father’s criminal ways must have affected them … “the fear of him being away and doing something was too great to sit at home and watch TV. We would go along with him and wait in the car,” he said.

Doug argues though that his brother “never wanted to go with Dad … I only remember my brother going on one job. Mum went too. Dad broke into an electrical store and I remember he came out and asked each of us what we wanted. He basically asked us to fill out a shopping list, then he went back in.”

But eventually his dad was caught red-handed by police with a stolen safe.

“When they interview him, he tells them it’s his first burglary, tells them that he was a copycat who had decided to rob a post office after reading about all the post office burglaries in the paper,” says Doug.

But of course this argument would have been shown as a lie had the police found any evidence which suggested otherwise. So, while their dad was still in custody, the boys decided to dispose of the dozen or more ransacked safes still scattered around the safe house.

Even though they are only 13, they drive the family Vanguard to the safe house and load one safe at a time into the car, drive to a nearby bridge and tip each one into the river.

“We dumped so many safes in there that I thought they would end sticking up over the water line,” said Doug.

The significance of the boys’ actions — whilst important from a criminologist’s point of view — certainly didn’t register on the twins’ personal Richter scale.

Disposing of evidence, hindering a police investigation … they were some of the charges the boys could have faced had they been caught. It was the first time they had performed a criminal act that wasn’t at the direct urging of their criminal dad.

But Doug shrugged it off back then and shrugs it off today. “I don’t think we thought twice about it. We both knew the safes had to be dumped … (for us) it was just the normal thing to do.”

Part two of this book extract series will appear in the Sunday Herald Sun.