Policing in the 1980s: The Case of the Cardigan and the Jewellery Penis

THEY were two rookie cops making their first big bust and determined that the police ‘Glory Boys’ wouldn’t edge them out — but in 1980s’ policing there was so much more to worry about.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

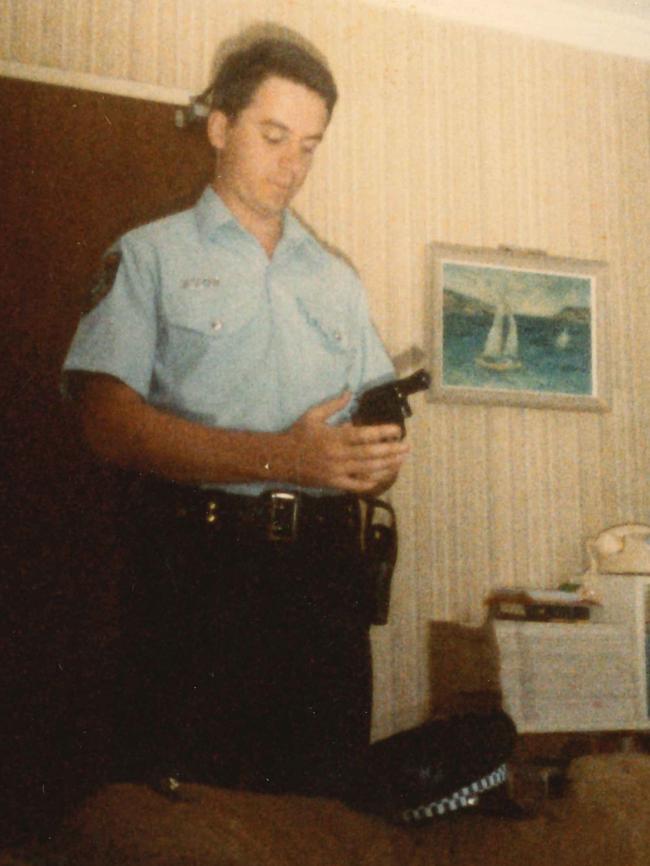

WHEN retired policeman John Verhoeven agreed to share details of his career with his writer son, the true crime stories that emerged revealed the dramatic — and sometimes dodgy — moments of policing Sydney in the 1980s.

In this extract from Paul Verhoeven’s book Loose Units, John and his partner Julian Carpenter tackle what they would later dub The Case of the Cardigan and the Jewellery Penis.

Picture special: Policing Australia in the ’60s

Dog Day Afternoon: Real-life siege like Pacino movie

BOOK EXTRACT: It was around 11am, and it was sunny. That morning there’d been a rash of break-and-enters happening all over North Sydney. First at 7am, then at 7.30, then 8am … someone was flitting around the suburbs and removing people’s valuables with remarkable proficiency. By lunchtime the two young officers had spent plenty of time lamenting the lack of ‘real’ police work thrown their way, and were getting wound up by this ongoing, real-time narrative of burglaries in their area.

And then the radio put out a call for assistance. The biggest break-and-enter yet had just taken place, and it was less than a minute from their current location. Julian and John reached for the radio at the same time. ‘You take it,’ John said, beaming. Julian snatched it up, answered the call, and they thundered into action.

Moments later they’d arrived at the crime scene.

Along with everybody else. They cruised past the stately two-storey home, ringed by onlookers and hemmed in by police cars from surrounding areas. Evidently, VKG was so determined to stop this crime spree that they’d flooded the area with a web of patrol cars from surrounding stations — there were cars from Cremorne, Neutral Bay, even over the Bridge.

Julian whacked the dash, frustrated. They slowed to a stop about twenty metres from the house and sat there surveying the crowd.

‘How much do you reckon they took to get this kind of a turnout?’ Julian remarked, eyeballing the people milling around the police cordon, as more cars came pulling up from arsehole to breakfast. From their vantage point they had a fantastic view of the action they were missing. John scanned the crowd, bored and annoyed. Which was when he saw the young man.

He was dressed quite well, in a cardigan and chinos, hair freshly cut, late twenties. He was walking down the hill towards the police cordon, and wasn’t slowing down or acknowledging the crowd. But John immediately clocked a few things that were off, apart from him being the only person there who wasn’t even looking towards the s---tstorm outside the immaculately appointed California-style home. He was, first of all, younger than anyone else there by a good fifteen years. Secondly, he had slightly longer hair than anyone else there — this might seem like a small detail, but it was enough to raise the ‘you’re not from here’ flag. John realised he’d just profiled someone based on appearance without realising he was even doing so.

‘How clever’s that?’ Julian muttered.

‘The cardigan?’ John replied, leaning forward.

‘Yeah. Rob a place then walk back and straight past the scene of the crime. Clever.’

John nodded. He and Julian peered at the young man.

There was a pause before John cleared his throat.

‘I mean, it might not be clever. ’Cos it might not be the guy.’

Another lengthy pause. Then, at the exact same time, completely unprompted, they both spoke in unison.

‘It’s the guy.’

Julian laughed, and clapped John on the back.

‘F---en’ oath.’

The cardigan briefly began to whistle to himself as he crossed in front of their car and made his way past two highway patrol bikes.

Julian groaned.

‘Cockroaches. Whenever you need them, they’re nowhere to be seen. Put out a call for something exciting like this and they f---ing congeal. You wait. Second this is over and we call for their help on a milk-run traffic case they’ll magically be nowhere to be seen.’

He strummed his fingers along the gearstick, restlessly eyeing the retreating cardigan.

‘Come on,’ said John.

The cardigan was walking down the street and had just nonchalantly turned the corner when John and Julian’s patrol car came to a stop next to him. He came to a halt also, and looked up. ‘Oh! Hi. Something wrong?’ the man asked, in a very well-spoken voice.

John hopped out. Julian came around the side and pulled out his notepad. As they made polite small talk, they must have looked to any onlookers paying attention like two police officers chatting with a local about whether they’d seen anything suspicious. Yet John was fairly sure there was something wrong with this one.

Which was when John noticed the erection.

The young man’s pants were standing to attention, the fabric of his beige chinos bulging out in John’s direction. John felt momentarily bad for the guy then a little flattered. Then he decided to bite the bullet and follow his instincts.

‘Sir, we’d like you to come to the station with us and answer some questions.’ And bafflingly, despite them having no real grounds to question this man, especially not in an official capacity down at the station, the man in question politely, quietly complied.

Moments later he was sitting in the back of the patrol car and they were heading towards North Sydney station. John could scarcely believe this.

Julian had elected to drive, and John made sure to sit in the back seat. His rationale for this was based on something Dunne had told him: never let a thief out of your sight. If the cardigan was carrying any purloined goods and John wasn’t keeping an eye on him, he could shove them down the gap between the seats, making charging him nearly impossible. What they really should have done was call for the wagon from North Sydney — a vehicle which left nowhere to stow stolen goods — but John and Julian were on the same page here. After piling the man into the car but before pulling away, they’d agreed: they didn’t want anyone else getting kudos for this.

That day, you see, they were working out of Mosman, which was a small substation, a low-rent offshoot of the North Sydney station. Every couple of weeks you’d have to hop over to the adjacent suburb and operate out of a sister station that was smaller and looked down upon. Mosman tended to get the s---tier jobs, and the glory boys working over at North Sydney tended to yank the big collars away from Mosman for themselves. Calling for a wagon would have meant tacitly putting this potential suspect in the hands of someone else. So when John and Julian walked their cardigan through the doors at Mosman and explained to their station officer for the shift — a man named Ted — what they were doing, his perpetual simmering resentment at having credit taken away and his read of John and Julian as enterprising young blokes with good heads on their shoulders overrode his desire to follow protocol.

‘All right, f--- it,’ he said. ‘Back room, quickly.’ He gestured down the hallway. And so they went.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

The room was just like those you’ve seen in the movies. A small, plain white table, soundproof walls, a typewriter, several chairs. They all sat down, and after a few minutes of polite chat with the cardigan, John and Julian learned a great deal more than they’d anticipated.

First off, he was nice. Very nice. Which might seem extraneous, but character goes a long way when you’re assessing someone’s guilt. He was from the eastern suburbs, near Rose Bay, and his father owned a very well-known jewellery store in the Strand Arcade. High-end stuff. Eventually, John cut to the chase, and, not unkindly, ventured, ‘Is there anything you’d like to tell us?’

When he said no, Julian informed the young man that they’d now have to search him. They then had him stand with his hands against the wall and his back to them and began to pat him down.

After searching him up and down, and finding nothing, John once again eyed the still buoyant erection. He cleared his throat, looked at Julian, looked back at the erection, and decided to roll the dice.

He stepped forward and closed his hands around … a jangling mass of metal.

‘Sir … please remove your pants,’ John said, now practically humming with adrenaline at his detective-grade intuition, and his relief at not having just closed his hands around a suspect’s d---.

Within moments the interview table was covered in an array of immaculate jewellery. The young man was so relieved to no longer have the stolen rings, necklaces and gems jostling his balls, and to no longer have to hide what he’d done, that he was decidedly lighter in his demeanour. And much in the way that a long-practised menial task can distract someone from trauma, so too was the man lost in the task of arranging each stolen piece into piles based on where he stole them. There on the table, a glittering map of each burglary was laid out — a diamond ring and three necklaces from here, a pendant from there, and finally a mass of assorted jewellery from the place they’d spotted him, as well as a roll of bills. The young man seemed happy enough talking them through what made certain pieces more valuable than others, manipulating them lovingly with a practised hand under the lights, sharing with them titbits on how they were crafted.

He seemed happy getting lost in the finer points of how the stones were cut, and in his mind’s eye, John could imagine him working in his dad’s shop down at the Strand Arcade. He thought about his own dad, Henk, and wondered if they could have ever ended up working together. He suddenly felt very sad, and very young.

All in all, there were easily sixty pieces of jewellery there. He’d had close to a quarter of a million dollars’ worth of jewels next to his jewels.

Dad lights up here. I’ve not mentioned this yet, but I should point out that for the past twenty years, he’s been an antique dealer and valuer of fine arts, and a damned good one.

Every year he pores over catalogues from auction houses the world over, memorising prices and valuations. He applied his eye for detail — honed while in the police force — to his new profession. So he leans forward and says ‘one of these pieces … knowing what I know now … had a six carat emerald beset by diamonds. Today’s money? Three or four hundred thousand dollars. Minimum.’

I am reeling. This was a staggering series of robberies carried out by someone who knew what the most valuable pieces were, because they’d been raised by an expert jeweller.

I wonder whether this heister ever thought about how different he’d turned out from his dad, too.

At no point did it occur to John or Julian to head out and tell anyone to call off the massive grid of officers from (as we’ve established, but it bears repeating) arsehole to breakfast because they’d caught the guy. These two were ambitious. John wanted to make big collars with someone who felt the same way as him, and, as the two of them had worked seamlessly in easing information from their suspect, their eyes gleaming, it became apparent that Julian was the partner he’d been looking for since he joined the force.

They could do great things together. And what a score! What a stunning haul to kick off what he knew, deep down, would be an amazing career. And they’d done it without an ounce of cruelty towards the young man who sat before them. They’d talked it out of him.

And he’d volunteered more than they’d bargained for, too. He explained that he was struggling with an ongoing drug problem, and that he figured taking stuff from a well-off suburb would hurt people less. He explained that he didn’t want to steal from his dad’s stock. He owned up to everything, and he did so clearly, politely, and regularly asked if they needed him to repeat anything. He apologised, but he didn’t feel sorry for himself. In the end, John and Julian found themselves feeling bad for the guy. They excused themselves, locked the door and headed back out to ask Ted for advice.

Ted was impressed. Beyond impressed. There was a rub, though. ‘Guys, this is … It’s great. But this is a detective’s brief. He’s gonna be charged with an indictable offence. Wouldn’t be if it was just a few pieces, but the value of the goods pushes this way, way out of your league and right upstairs. Glory boys get this.’ He looked sorry, too, and could see how utterly gutted John and Julian both were. He spoke up again, and gestured back towards the interview room. ‘I’ll call them, but I’ll give you another hour. So you can get what you can. If you can crack it by then, great. You’ll get some credit, at least … getting an itemised list from the perp with which jewels came from where would be quite the achievement. You could impress some big names that way. Otherwise, the detectives have it.’ John, without meaning to, rubbed his hands together.

John and Julian had a hushed powwow before their next move.

In order to try to weave themselves, and their accomplishments, into the narrative of this case, they resolved to take the now totally compliant suspect on a tour. They bundled him back into the car, and he then took them from burgled house to burgled house, itemising every single thing he stole from each one. He even took them past places where nobody had been home, meaning robberies in his spree that nobody, not even the cops, knew about yet.

John was frantically trying to take notes for later on, so they could line up each list with what they had back in evidence. The information flowed from him freely, and once they’d returned to the station he looked as if he’d taken a very long piss he’d been holding on to for days on end. Here he was, with two nice young officers, and he finally had all his cards on the table. No more secrets.

They sat back down, and John said those nerve-racking words: ‘We’d like to get a statement from you. On the record.’ Up until this point, it had felt friendly, confessional. But now they were about to officially stamp the case as theirs, still with some time to spare before their hour was up. The cardigan, sensing this was a big moment, and perhaps sensing that his future was on the line, asked for a phone call.

Julian, politely and without missing a beat, said, ‘No, no phone call, mate.’ He knew that if this guy got his phone call, he’d get onto a lawyer, and once that happened, game over. It was illegal, but Julian figured it was best to gently shunt him away from that option. The cardigan looked at Julian, then at John, then thought a moment. And finally, he smiled. ‘Fine. What’s the harm, I’ve come this far. Yeah, I’ll give you a statement.’

John couldn’t believe it. A suspect in a massive jewellery heist was somehow willing to forgo legal entanglements, and was going to officially throw this entire collar in the hands of himself and Julian, two rookie cops, on their first time out together. This was fate. This was incredible. Cardigan cleared his throat, and Julian, eyes on fire with anticipation, readied his hands on the typewriter.

And that’s the exact moment the glory boys burst into the room.

The boys are back in town

‘All right, c---heads, let him have his phone call.’

The lead detective, a man with a ponytail and a film of sweat on his face, erupted into the room chest-first. His cohort, who had dead eyes and the loping gait of a gorilla with ideas above its station, trailed in behind him. Both wore ill-fitting suits. Both looked like they were a whisper away from punching John and Julian through the adjoining wall.

John ventured a ‘But he was about to —’ before the gorilla cut him off. John wondered if this gorilla was related to the one he saw across from him in the study room at the academy. For a brief moment, he could have sworn the man actually was a gorilla, his suit suddenly snug, his knuckles dragging on the lino floor.

‘We were watching just now, we don’t give a s---. Not your case any more. He gets his phone call, and you can get the f--- out.’

John looked over at Julian, his heart racing. For the briefest of moments, he could have sworn Julian was going to deck the ponytail. Thankfully, Julian stood up and grabbed the notepad with the details from their tour of the robbery sites. Ponytail yanked it from his hand and brandished a finger towards the door. John and Julian filed out. The door slammed behind them, and feeling more than a little hard done by, they rushed over to Ted.

‘Sorry, lads. They got here early, no idea how they found out.’

John smiled weakly. He and Julian decided to stick around for a bit, out of sight if possible, to see how things washed out.

Here, then, is how things washed out.

First, the primates who’d burst in had ensured that Cardigan was allowed his phone call. He made this call to his father, who naturally insisted he lawyer up, and also that he refuse to give a statement, meaning the litany of kudos John and Julian were due for was about to get burned to a crisp.

Secondly, the glory boys justified their nickname by taking credit for the collar. As everything John and Julian had done so far was off the record, this was easy; John would later go through the paperwork and see no sign of himself or his new partner.

The final insult, however, was the worst. Eventually, the two of them left and resumed their shift back out on patrol. Several days after that they were tasked with taking Cardigan over to the District Court where he was being tried for robbery (a significantly trickier process, now that his confession was off the table). They decided not to poke the bear and avoided grilling him on the way over, but by the end of the drive, all three of them were laughing and joking and telling stories. Yet again, they were reminded of how much they liked this guy.

And after checking Cardigan in to the courthouse, Julian had the bright idea of calmly asking if he could see the charge book, an enormous tome which detailed, in tiny precise handwriting, exactly what each person present was being charged with. Julian scanned down the page and suddenly stopped. All the blood drained from his face. He gulped, his mouth hung open, and pointed to the open page before walking off like a man suffering a recent loss. John, puzzled, headed over to the book and began to read.

There, next to ‘on such-and-such a day, in the year of our Lord, under 14-7 of the Crimes Act, pursuant to’ et cetera, et cetera, was the section detailing the total value of what had been stolen.

That figure was $3000.

It was John’s turn to go pale. ‘Oh, s---.’

• This is an edited extract from Loose Units by Paul F. Verhoeven (Viking, $34.99) available now.

Originally published as Policing in the 1980s: The Case of the Cardigan and the Jewellery Penis