One tiny detail in Milica Trailovic murder that haunts former detective Narelle Fraser

It took a spray of Luminol to show the blood stains on the seemingly spotless couch where Narelle Fraser had sat to question Tony Serrano, but it was what investigators found next that sickened the senior detective.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

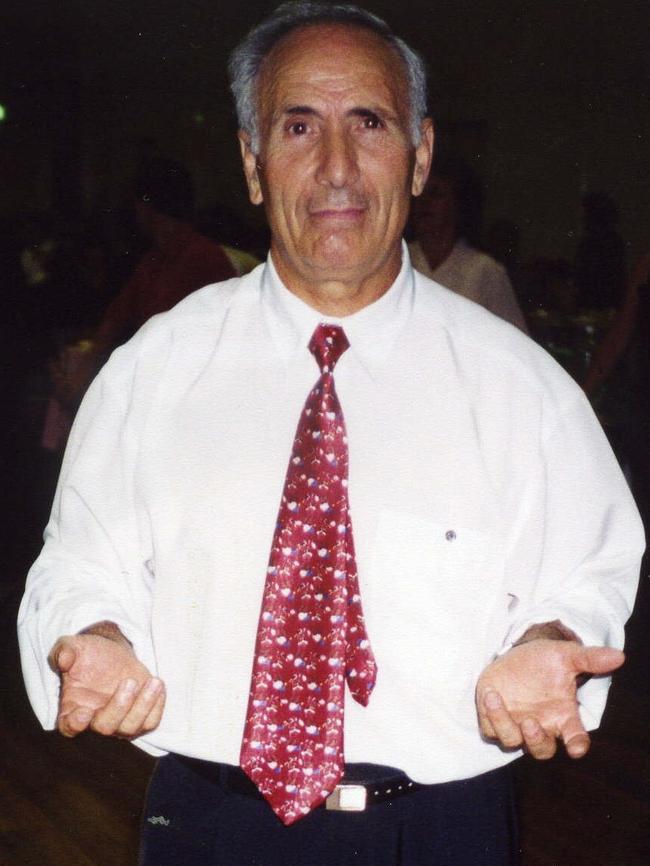

When Senior Detective Narelle Fraser sat on a couch with Apolonio ‘Tony’ Serrano to question him about his partner Milica Trailovic’s disappearance, nothing seemed out of place in the clean and tidy Victorian home.

It would take a later search warrant and a spray of Luminol to show up the blood spatters on the couch and across the room.

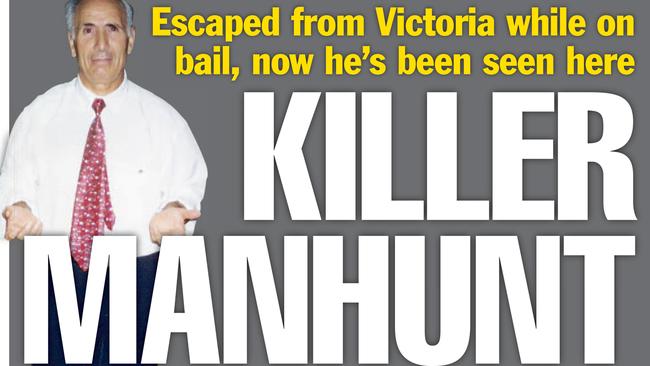

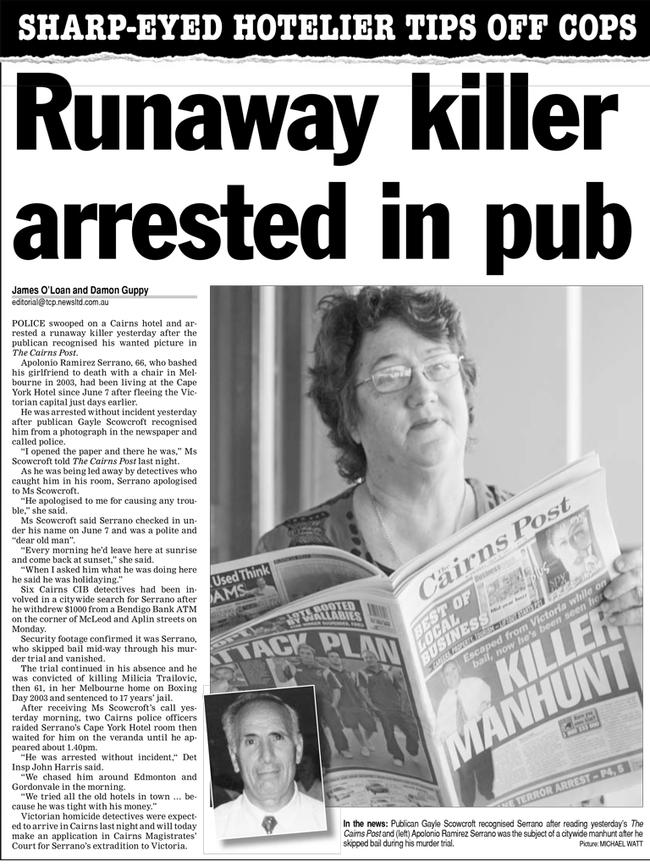

Tony would later go on the run, and was found guilty of murder in his absence, before being tracked down in Cairns.

But he never revealed the whereabouts of 61-year-old Milica’s body.

In the edited extract from Unsolved Australia: Lost Boys, Gone Girls, below, author Justine Ford, who previously wrote The Good Cop, examines the case — one of 13 explored in the book.

One shocking discovery in that home still haunts Fraser.

Bronwynne Richardson: Beauty queen teen killed and dumped in river

Cold case murder: $1 million reward to solve execution of Antje Jones

Sussex Street Mystery: Killer butcher exposed by ‘stupid’ act

It is common knowledge that when someone goes missing under suspicious circumstances, or they are murdered, police investigate those closest to the victim first. The reason for this is simple: the majority of homicide victims are known to their killers.

Milica had no family in Australia so that ruled them out. She was closest to her partner Tony so the investigators had to look into his background.

What Narelle found out about him at the start was strange but not necessarily sinister. ‘He was besotted with money,’ she says.

‘When Milica stayed at his house he asked her for money for the electricity, for the shower, for water.’ Eventually, Milica decided such payments should work both ways and asked Tony for money to cover electricity and water when he stayed with her, too.

Neighbours, who last saw Milica on Boxing Day (2003), told Narelle of hearing a loud argument at her place. ‘It was either on Christmas night or the following day, and they heard Tony’s car leave late at night which was very unusual,’ Narelle says. ‘We were now starting to get a bit of a picture. He was all about power. I think he had little man syndrome. Milica was a big woman. She was a matronly woman, at least six foot and probably a size twenty-two. They were like chalk and cheese.’

Milica regularly spoke on the phone to her sister in Serbia and had talked about her relationship with Tony. It wasn’t all roses. ‘Her sister knew that she was arguing with him,’ Narelle says. ‘She didn’t trust him.’

Yet there was no evidence to indicate that Tony and Milica’s arguments were anything more than tiffs and there had been no suggestion of violence in the past. The only way to find out exactly what happened to Milica was through old-fashioned detective work. As two investigators took a statement from Tony, another searched his bank records, Medicare and phone accounts and two others prepared a warrant for a meticulous search of Milica’s house. In the meantime, two other detectives conducted a fresh doorknock.

‘Dandenong Police had already done a doorknock,’ says Narelle, ‘but we asked different, more involved questions because we had more time.’ The fresh doorknock yielded more information. ‘We found out that Milica hadn’t gone to a dance as planned about two nights after Christmas.’ The detectives also confirmed that Milica had not been seen since around Boxing Day.

The investigation started hotting up when the detectives found out that after Milica went missing Tony had visited a doctor with a broken finger, which he said he’d caught in a door. Narelle recalls thinking, Either he’s telling the truth or Tony injured himself another way — perhaps assaulting Milica?

Narelle’s interest in Tony as a suspect heightened when detectives discovered that, between Christmas and New Year, Tony, a man of independent means, had been trying to find out if he was a beneficiary to Milica’s will. First, armed with a copy of the will, Tony visited the woman who had witnessed it. He then met with the solicitor who had prepared it. Lastly, he asked to see a lawyer at the Serbian Welfare Association, saying he was trying to find out where the will was located, which was strange, considering he had a copy.

A day or two into their investigation, the Homicide Squad Missing Persons Unit was granted a warrant to search Milica’s house. What they found was straight out of a horror movie.

Despite appearing immaculate to the human eye, when sprayed with Luminol the combined lounge and dining room was spattered with blood. ‘There was blood on the walls and smear marks where it had been cleaned,’ Narelle says with a shudder. ‘There was blood on a cushion and on an armrest of the couch where we’d been talking to Tony. From looking at the scene, the blood spatter expert was able to tell us Milica had been hit with something while standing, while kneeling, and then while she was on the ground.’

In the light of this new knowledge, the investigators started looking for a weapon. ‘We noticed there were three chairs at the dining table,’ Narelle says. ‘Normally there are four or six and we believed one was missing from the table.’ They did not have to go far for an explanation. Behind the garden shed they found two broken chair legs which were the same as those at the dining room table. One of the chair legs was flecked with blood. They also found a pair of smashed reading glasses — probably Milica’s.

Back inside the house the investigators observed that a piece of carpet in the living room was missing and covered with a mat. It looked innocent enough, but it led the crime scene investigators to the discovery of a human tooth wedged in between the skirting board and the carpet in the living room. ‘I felt a bit ill when I saw the tooth,’ Narelle says. ‘You’d have to be belted senseless to be missing a tooth. It was a really awful feeling.’

The turning point in the investigation came when the police could not establish that anyone other than Tony had been in Milica’s house around the time she went missing. ‘That’s when everything changed and Tony Serrano became a suspect,’ Narelle says.

Tony was formally interviewed at Victoria Police Headquarters in St Kilda Road. For a few minutes Narelle was left alone with Tony in an interview room while fellow crew members fetched him some water. Looking back, Narelle suspects her colleagues left her alone with him because she had a knack of getting suspects to spill.

‘I was thinking, Oh my God, I’m in a room with someone who I’m pretty sure belted a woman senseless,’ Narelle says. ‘It was a bit uncomfortable.

Obviously you keep a chair or table in between you. It was only fleeting but I thought, God, what am I doing here?’

During the interview with Tony, Narelle was rattled by his behaviour. ‘He was uptight, nervous and aggressive,’ she says. ‘He would turn the interview around and was so argumentative and bombastic that you’d ask him a question and he’d say, “Why would you ask me a question like that?” In the end it was like he was trying to take control of the interview. He was a control freak and a very angry man.’

Narelle wondered what growing up in a postwar orphanage had done to Tony Serrano. ‘I think he was intimidated by women — and women in power in particular.’ Still, that did not mean she felt sorry for him. ‘I didn’t like him and he didn’t like me,’ she says. ‘He was a sly little p----.’

It was rare for Narelle to play the bad cop; her whole career had been built on being the good cop and making genuine connections with people. Neither approach was going to work with Tony Serrano because he was making no admissions no matter how much she asked for his side of the story. ‘If we didn’t give him that opportunity it could have been criticised in court and thrown out,’ she says.

Circumstantially, it looked like the hostile suspect was responsible for Milica’s disappearance, but Tony Serrano raised a fair point.

‘In his interview he said he couldn’t lift her,’ Narelle says. ‘And he had a hernia.’ So if he’d killed Milica, how had he removed her from the house and disposed of her body? The detectives needed more evidence if a murder charge were to stick. ‘We had a lot [of information] but we needed another piece of evidence to charge him,’ says Narelle.

When Milica’s neighbours told police that Tony was frequently going out and not coming home until late at night, the detectives hatched a plan. Hoping his late-night outings might lead them to Milica’s body, the detectives put a tracking device on his car. ‘The other reason we decided to use the tracking device was because he’d got a speeding fine up Newborough, Moe, Morwell way and we couldn’t establish why he’d been there,’ Narelle says. The area in which he’d been clocked speeding was in Victoria’s La Trobe Valley, a regional area more than an hour’s drive from Endeavour Hills.

The tracking device showed Tony’s car returning to Newborough and stopping for two minutes in a secluded area off a bush track.

Narelle knew it was the kind of place where a killer might dump a body. Straight away the police assembled a search party and headed to the scene. Within a few hours they made an incriminating discovery: a pile of badly burnt plus-sized clothing and a pair of women’s shoes. ‘The clothes were a size twenty-two, and the shoes a size eleven,’ Narelle says. They were Milica’s style and size and had been there a while. It looked to the investigators like Tony had come here to, at the very least, dispose of her clothes.

Even though there was no sign of Milica’s body, the police now had enough evidence to charge Tony Serrano with Milica’s murder. ‘Looking back, I’m pretty sure the tracking device and the discovery of the clothes was the clincher,’ Narelle says. Statements from Milica’s neighbours compounded the case against him. ‘But still, he never ever admitted it.’

The detectives prepared a brief of evidence. In order to prove that the DNA at Milica’s house was hers, they needed to compare it against the DNA of a relative. The detectives asked to go to Serbia to get a sample from Milica’s sister but their request was denied as it was too expensive so the team came up with an alternative plan. ‘We had a DNA kit sent by registered post to a doctor in Serbia and he went to see Milica’s sister,’ Narelle says. ‘It was enough for us to say it was her DNA.’ The blood on the chair leg was Milica’s too, which suggested it had been the weapon used to bash her.

****

To this day, Narelle mulls over how Serrano could have removed Milica from her house and disposed of her body. ‘She would have been a dead weight. She would have been very heavy,’ Narelle says.

‘I wonder if he cut her up and used his skills as an excavator to bury her.’

Over the years, Narelle successfully investigated scores of missing persons cases, murders and other violent crimes. It’s the kind of work that can come at great personal expense when police struggle to shake off violent images. For Narelle, the Milica Trailovic case is yet another terrible crime that sticks in her mind. ‘It’s because of the tooth,’ she says. ‘And I thought it was very sad that it happened in Milica’s own house at the hand of someone she trusted. Seeing the blood everywhere with the Luminol, I thought, That poor woman. What must she have gone through?’

And even though justice has been done, one piece of the puzzle is still missing.

‘Tony Serrano is now in Her Majesty’s Prison,’ Narelle says, ‘but where is Milica?’

• This is an edited extract from Unsolved Australia: Lost Boys, Gone Girls by Justine Ford, published by Macmillan Australia. RRP $32.99. Available in all good bookstores from June 25 and on preorder here