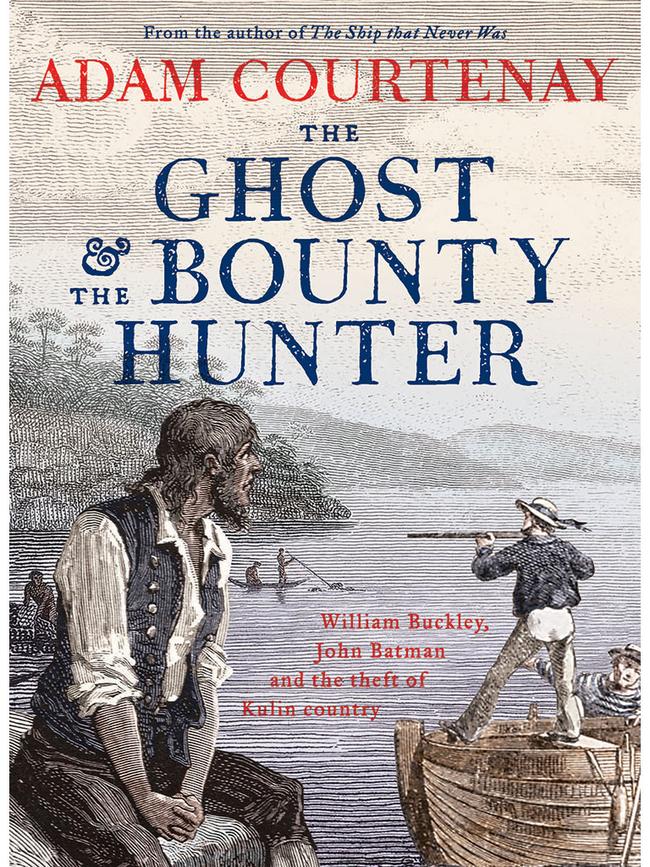

Book extract: The Ghost and the Bounty Hunter by Adam Courtenay

In need of a true crime book binge? Get started with Adam Courtenay’s new work on convict William Buckley’s incredible life, then check out a dozen other titles thanks to True Crime Australia.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- True crime book extract: The Pretty Girl Killer

- True crime book extract: The Expert Witness

- True crime book extract: The Fine Cotton Fiasco

The story of William Buckley is one of Australia’s most extraordinary convict tales. Discover how it all began in these extracts from The Ghost and the Bounty Hunter by Adam Courtenay.

As Christmas 1803 approached, the colony was in emotional turmoil. Ever since the commandant (David Collins) had declared they would be leaving Port Phillip, rumours had spread of a major breakout of convicts – possibly even a mutiny. While stoked more by fear than reality, there was truth in this gossip. The half-built colony was in the process of unbuilding itself, and in the confusion tensions were heightened.

December brought searing heat. There were flies by the thousands by day and mosquitoes biting at night. Members of all social classes succumbed to sickness, but this had little effect on Collins’s determined quest to abandon the area. He ordered there be no rest days, which meant the convicts were in gangs working from sunrise to sunset. ‘Carry on’ was the message delivered from above. The women were still undertaking domestic work, creating vegetable gardens with the help of their children, but there was a sense of unease.

MORE TRUE CRIME BOOK EXTRACTS

Murder, Misadventure & Miserable Ends

Like many others, William Buckley watched in dismay as the colony he had helped to build unravelled. By early December he was part of a team ordered to build a 380-foot jetty for the next operation – reloading onto the ships all the stores they had recently unloaded.

To everyone except Collins, this all seemed like an anticlimax. They had been prepared to make this country work. As the wife of one officer, Mrs Hartley, remarked in a letter to her sister, ‘My pen is not able to describe the beauties of this delightful spot.’ The colony, she muttered, was being abandoned ‘at the whim of the governor’. She ended the letter: ‘I parted from it with more regret than I did from my native land.’

With fewer able-bodied men on watch, Collins couldn’t maintain the usual standards of security. Buckley, chafing for freedom, knew he needed to act soon. He decided to bolt for Sydney that month.

What did he have going for him? Added to his immense strength were qualities of self-reliance and resilience. When he had fought in the army his height had guaranteed him a position as a ‘pivot man’; in the heat of battle soldiers needed someone to rally around, and Buckley had been that man. He was calm under pressure and battle hardened. While determined in character he was also gentle in nature, emotional and sometimes given to self-doubt. He wasn’t one who found self-expression easy, but underneath it all there was grit, resourcefulness and determination. Buckley was the archetypal gentle giant. He believed – perhaps naively – that whatever this new continent threw at him, he could handle.

All the ‘cavorting’ among the colony’s wealthiest denizens wouldn’t have gone unnoticed by Buckley and his fellow convicts, nor the fact that the officers and their men were frequently drunk. In fact, to improve morale Collins had offered them double rations of grog. The hardworking convicts, of course, received nothing. Across the board, a climate of sickness, despondency and ennui prevailed.

MORE TRUE CRIME BOOK EXTRACTS

Unsolved Australia: Lost Boys, Gone Girls

Life Sentence, My Last Eighteen Months (Carl Williams)

Among the inmates’ ranks were a number of radicals who held their greatest rancour for members of the upper crust. There was one George Lee, mentioned by Tuckey and Collins as a man of ‘considerable education and abilities’, who was granted special dispensation for being something of a gentleman. He was given a hut and light duties, but Lee abused his role, as Collins put it, by ‘misapplying the leisure’ that he had been given and ‘endeavouring to create dissatisfaction among the prisoners’. Lee had apparently written some scurrilous verse about the officers. ‘I would rather take to the bush and perish sooner than submit to the torture to please the tyrants, the ignorant brutes placed over me as slave drivers,’ he reportedly said when asked for his views on colonial life. When Collins asked Knopwood to inquire more deeply into the man’s background and current activities, it became obvious that Lee was a firebrand, influential and dangerous. Immediately he was put in a gang for hard labour. But he was influential, and his punishment did not deter the convicts. It hardened their resolve to flee.

In the end, though, it was just Lee and his mate David Gibson who bolted. Lee stole a gun and made a desperate run for it. He was never heard of again, believed to have (as Collins would describe in his periodic reports to King) ‘perished in the woods’. When Gibson returned a few weeks later, he was unrecognisable. He stumbled into the camp, raised his hands and practically walked into the leg irons awaiting him. The flogging he received was a blessing compared to the rigours of the bush.

Despite their failure, Lee and Gibson had succeeded in igniting the first wave of desertions. Gibson’s wretchedness, after his bush ordeal, did not discourage them. They all knew that if they were transported south to Van Diemen’s Land, escape would be next to impossible. By December, as Buckley and a group of friends were contemplating their breakout, fourteen people had already fled.

Anyone who relished liberty, anyone who truly believed the ‘liberty or death’ credo, would make a run for it. ‘I determined on braving everything,’ Buckley wrote. This, he said, was due to his ‘unsettled nature’ and his ‘impatience of every kind of restraint’.

And so it was that William Buckley, Dan McAllenan, George Pye, Jack Page, William Marmon and Charlie Shore plotted their escape, hoping that just after Christmas, with the rum ration doubled, most of the sentinels would be off their guard, if not drunk.

Buckley and his troop didn’t look to abscond across the hinterland. That way, they thought, lurked countless savages. The band of convicts would begin their escape in the backwoods behind the beach and then double back to the coastline. They would then head north for about fifty miles to the top of the bay, and from there they would cut across country and head direct to Sydney. Their greatest hope for survival was a fowling piece – a rather ramshackle gun that McAllenan had secreted – to shoot possums and kangaroos.

Christmas passed, and all was quiet in Sullivan Bay. At nine o’clock at night on 27 December, six men went on the run with a few tin pots, an iron kettle and a second-rate gun. They had just a few days’ rations between them. A green, beautiful but ultimately alien wilderness awaited them.

Buckley and his crew had only just crept their way into the woods behind the encampment when they heard shouts from the sentinels followed by the sharp crack of a rifle. Their hopes of putting distance between themselves and their pursuers were foiled, but they carried on. The six men ran into the woods as fast as their legs could take them. A posse of soldiers was coming. In the race for freedom, it was every man for himself.

Buckley increased his pace, and Pye, Marmon and McAllenan responded. They’d barely covered a few hundred yards when the air resounded with thunder followed by flashes of lightning. Within seconds, there was heavy rain.

When Buckley heard the report of a rifle, he looked back to see Shore writhing on the ground, badly wounded. Page had stayed with him, deciding not to risk the run. It was now just Buckley, McAllenan, Marmon and Pye.

They pressed on, heading back onto the coastline and running north along the sand in the darkness, skirting dunes at speed, every now and then crossing minor streams that emptied onto the beaches.

Occasionally a bolt of lightning illuminated the territory ahead but mostly all they could see was sea, sand, trees and rocks amid a haze of rain and sweat. The creeks slowed them as did the rocks around the headlands, and there were marshlands to negotiate as well.

Just before present-day Rosebud, they found themselves trudging across the onomatopoeic sounding Tootgarook Swamp (Boonwurrung: croaking frogs), which reached to the sea and extended several miles inland. The atmosphere cleared, the humidity dropped and, after four hours on the run, the men paused to gather their wits. They had shaken off their pursuers. Their clothes were dripping from rain and exertion, and it was only now they realised four had become three – Marmon had been unable to keep up and had turned back for the settlement.

‘We now pushed on again until we came to a river, and near the bay; this stream the natives call the Darkee Barwin,’ noted Buckley. This has been identified as present-day Kananook Creek, but that would mean they had run more than twenty-five miles, the equivalent of a marathon, in around six hours: not impossible but very difficult over wet sand, swollen creeks and wetlands. It’s most likely that they stopped at either Dunns Creek, a few miles to the north of Arthurs Seat, or Sheoak Creek, which drains from Mount Martha.

When daylight came, Buckley realised he had become the natural pivot man for his troop. It was now just he, McAllenan the Irish horse thief, and Pye – a convict who had been convicted for stealing sheep in Nottingham. Neither Pye nor McAllenan had military experience. Both were still exhausted, their bodies stiff, but they fell in line with Buckley, who was determined to move relentlessly northwards. They knew their provisions would barely last more than a few days, so they had to conserve their strength. But the weather grew steadily hotter, and their pace began to slacken.

We pick up their story a few days later …

At Swan Island, Buckley said they found an edible gum – it may have been that naturally rendered by the acacia tree – which they placed over the fire until it was soft and palatable. When morning came, they could survey much of the terrain they had crossed on the other side of the bay, but there was something else. Almost due south, they could clearly see the Ocean sitting calmly just off Sullivan Bay.

It was now a few days into the new year. The ship was only about ten miles along their line of sight. This was all too much for McAllenan and Pye – that way lay food, shelter and survival.

All three men tried to attract attention by starting fires and hanging their shirts from trees. It seemed to work: a boat left the opposite shore and was moving in their direction. Halfway across the bay, the boat stopped dead, tacked to starboard and headed back to shore. The currents may have been too strong. McAllenan and Pye started screaming at the boat while it kept pulling away. ‘The dread of punishment was naturally great,’ Buckley recorded, ‘yet the fear of starvation exceeded it.’ It was later reported that the fires had been seen at Sullivan Bay, but as the soldiers in the boat had approached they’d changed their minds, believing it to be started by the locals.

The escapees’ fires were henceforth ignored.

Buckley wrote they lasted another six days living on whatever they could scavenge from the coastline, before McAllenan and Pye resolved to return by foot. They had continued signalling to the camp across the bay but to no avail. ‘They lamented bitterly,’ Buckley wrote. The two men strongly entreated him to return with them, but the big man remained steadfast. He believed that with a bit of luck and perseverance, he could make his way through this country. It was a case of them needing him far more than he needed them. ‘To all their advice and entreaties to accompany them, I turned a deaf ear, being determined to endure every kind of suffering rather than again surrendering my liberty.’

Buckley’s companions left with some bitterness but no acrimony. He had made his decision. He was now alone, it seemed, in this strange but beautiful landscape, the untarnished England of his imagination.

McAllenan made it back to Sullivan Bay. He surrendered on 13 January, reportedly suffering from severe scurvy. As Collins noted: ‘Upon the 13th January, one of the wretches surrendered himself at the camp, having accompanied the others, according to his calculations, upwards of a hundred miles round the extensive harbour of Port Phillip.’ McAllenan brought back the Commissary’s fowling piece and stated that he had subsisted chiefly upon gum and shellfish. Pye was never seen by white people again.

It didn’t take Buckley too long to recognise his extreme vulnerability. He fell into a severe melancholy. Any idea of making it alive to Sydney had been sheer folly, and even if he had succeeded he would probably have been incarcerated.

The liberty Buckley had so hankered for had now become the source of his pain. He was, he wrote, experiencing ‘the most severe mental suffering for several hours’. Freedom, as he put it, ‘now made the heart sick at its enjoyment’. It carried heavy penalties. He would continue his ‘solitary journey’, he wrote. He would not speak to another white man for the next thirty-two years.

• This is an edited extract from The Ghost and the Bounty Hunter by Adam Courtenay (ABC Books, $29.99), in-store and available online now.