18 child convicts, one body and a dubious confession

It was “the most dangerous life” for a person, and at the British Empire’s first juvenile jail in Australia, it ended in murder.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

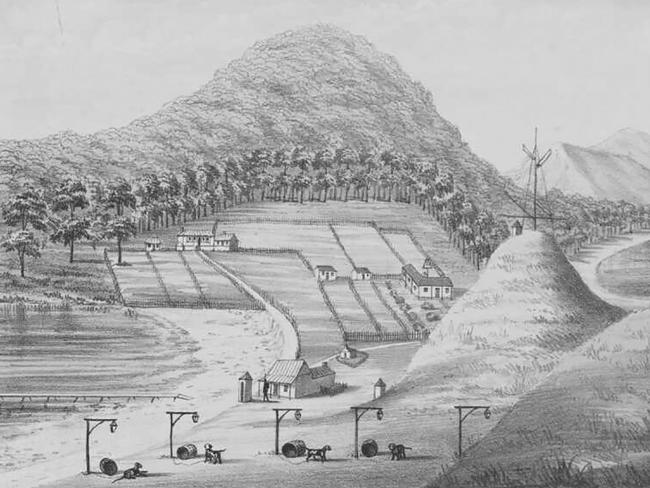

Tasmania’s Point Puer Boy’s Prison was the first juvenile jail in the British Empire, but separating the men — of nearby Port Arthur — from the boys didn’t make it any less harsh.

New book The Lost Boys of Mr Dickens tells the real-life story of two young boys sent from England to the prison — and the shocking moment the day-to-day violence of jail life escalated to murder.

ON 23 JUNE 1843, George Rose, assistant superintendent for the Point Puer Boys Prison crime class, was trying to keep warm as he stood waiting for the eighteen ‘worst’ boys to assemble for their afternoon muster in the gaol yard after the finish of their allocated dinner time.

Unexpectedly, one of the smallest boys approached him.

It was red-haired Charles Campbell. ‘The overseer of the boys is lying down in the yard,’ he said, as troubling as it was casual.

True Crime Australia: Is skull on beach key to cold case mystery?

Criminal history: Why Victorian cop was the real Sherlock Holmes

Hugh McGuire was one of the Port Arthur convicts assigned to help supervise Puer boys and had only been in the overseer role for two months. He was perhaps 30 years old and well-built, so there was no obvious reason for why he might be lying in the yard. Rose knew McGuire had been tasked with watching the ‘worst’ boys, and all convict overseers had to be on their guard against boys who strived to ‘emulate the men in everything’.

Some boys had already emulated men when it came to violence, having access to potentially lethal weapons such as stone hammers, chisels and spades, and the opportunity to secrete knives or manufacture their own. News of any violence at Port Arthur spread like wildfire at Puer. ‘If one man beats out his comrade’s brains with a hammer or another commits suicide, the circumstances with all the disgusting details is soon know to and talked of among the boys.’

Back in 1841, Puer was alive with talk of how Patrick Minnighan, also known as Minahan, ‘a most determined looking young man … a reckless hardihood’ had taken a stone hammer to James Travis, ‘a mere lad’ who had informed on his preparation for an escape attempt from a chain gang at Port Arthur, and how, standing over the dying boy, Minahan had declared, ‘there lies one bloody dog, stiff enough!’

John Childs, described as ‘a probation lad’ struck another boy on the head with a stone hammer after being called a ‘dog’, the Colonial Times reporting it as nothing unusual: ‘There was no particular feature in the case. Troy called Childs a dog, and Childs knocked him on the head for it.’ One group of boys was said to be so angered by another who consistently told ‘skunk’ tales ‘they pushed him over’ the cliffs, although authorities portrayed it as an accident.

William Scrimshaw burnt another boy with a red-hot iron. Henry Belfield, the illegitimate son of a surgeon, bashed and knifed a fellow prisoner.

George Rose well knew boys also had no time for most of their convict overseers, who they saw as merely older versions of themselves. Boys quickly identified any ‘good’ overseers they could work with — those willing to turn a blind eye to offences of blackmarket trading of food, clothing, tools, tobacco, or sexual activity — and those prepared to go even further and ‘connive … to avoid becoming unpopular’.

Overseers trying to insist on compliance would ‘only provoke ridicule’ and be ‘insulted or maltreated at every opportunity’.

Just as Commandant Booth had escalating punishments if his first did not produce an ‘amendment’, so did the boys. The first warning to overseers came in the form of a ‘crowning’, the tipping of a nightsoil tub over them, or perhaps the killing of a pet cat.

Boys would also make ‘disgraceful charges’ that they sought ‘to take liberties with them’.

Some overseers invited revenge, especially those who Inspector Horne said evidenced ‘the well-known fact that a slave in power becomes an intolerable tyrant’, or who authorities had to remove for ‘still more atrocious’ offences than those occurring at Port Arthur.

The House of Lords heard from the colony’s solicitor-general that being an overseer was ‘the most wretched and dangerous and the most miserable life that a person could lead in the colony’, a life risking ‘most murderous assaults’.

Making his way after Campbell into the gaol yard, George Rose would have been fearful of what he would find. No one at Puer could forget the day in 1840, when visiting Frenchman Captain D’Urville attended one of Booth’s hearings and was shocked by a small boy who had threatened an overseer with a knife and vowed he would kill the man. Even fresher in Rose’s mind was ‘a very wild happening’ the previous year when, at a given signal, boys extinguished the night lamps and with bricks pulled from fireplaces launched ‘a furious attack’ on an Austrian-born overseer Frederick ‘Adolphus Augustus’ Bundoch, ‘who was very much disliked’. The victim’s ‘screams of murder’ brought others to his rescue, but not before he was severely wounded and placed in the hospital for three months.

Could this be the day Benjamin Horne had recently warned of, that while boys had not yet fully copied men in ‘the highest class of crimes’ this was ‘no proof that some of them will not eventually do so’? The day when Commandant Booth and everyone in Van Diemen’s Land might confront something not seen, a case of boys committing a murder at Point Puer?

Inside the gaol yard Rose’s worst fears were confirmed. Just as Campbell had said, McGuire was indeed lying on the ground and ‘bleeding in the head’. He had arrived in the colony less than a year before. After serving nine months for poaching in his native Scottish border town of Peebles, 22 miles (35km) south of Edinburgh, he had been gaoled again for an assault but then broke out in his prison clothing and was captured and transported for fourteen years for ‘theft’. McGuire was marked in his gaol report as a ‘bad character’ but he gave Booth no trouble when he was despatched to Saltwater Creek, 15 miles (25km) north of Port Arthur, where about 400 convicts cultivated cabbages, potatoes and turnips.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook

The commandant rated his Port Arthur behaviour as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ with no offences recorded, and with his good build, avowed Protestantism and rare ability to read and write, seemed to be a convict with prospects of staying on the right path himself and worth the risk of assignment as an overseer at Point Puer in March 1843.

In his first eight weeks at Puer McGuire’s conduct was regarded as ‘orderly’ and ‘good’, and ‘very kind and humane’ to the boys.

But whether he was truly good and kind, or had been overzealous in his newfound responsibility, McGuire was now lying on the ground, barely alive with a bloody head wound.

Rose’s mind must have raced. Was this another case of revenge against an overseer seen to have over-stepped the mark? Or perhaps even the first case of boys emulating Port Arthur men in committing an apparently senseless crime because they were ‘tired of this life and resolved to do something [and] be hanged’ or because ‘I’d rather be dead than alive as I am now’?

Charles Campbell and seventeen others were staring, silently and sullenly, ‘all in a body, looking at [McGuire] at about three or four yards distance’. Rose eyed them all. He looked first at Campbell, but there was no way of knowing if his alert was out of any real concern for McGuire, if he had been despatched by other boys, or was just trying to appear tough. Rose next looked at Harper Nicholls. Sentenced in York to seven years transportation for stealing a gelding, he was one of ‘the most powerful’ of the boys, one he knew had ‘some quarrel the evening previous’ and been before the magistrate just thirty minutes ago on a charge of ‘indecent conduct’. He also looked at Daniel Miller, ‘a much stouter and taller fellow’, and John Smith, ‘a strong-looking youth’, who had also been before the magistrate that morning. Others he eyed included William Fletcher, a ‘rather tall’ lad of eighteen who had spent nearly four years on board the notorious Euryalus, Michael Shea ‘a stout, resolute looking fellow’, and Henry Sparkes.

Which of these boys had attacked McGuire? Many of them had been reported by McGuire for various offences, Campbell and Sparkes receiving their heaviest thrashings in McGuire’s short time as overseer, and several had just been before the magistrate. Was it a spontaneous revenge attack by one or two boys taken to the magistrate that morning, or another well-planned mob attack? And could boys have been bullied by others to exact some revenge on their behalf, and threatened if they informed?

Word of the assault quickly spread as Rose sent out alerts to Captain Arnold Errington, commanding officer of the 51st light infantry regiment at Port Arthur and the day’s visiting magistrate while Commandant Booth was on leave, Point Puer superintendent John Mitchell and Puer gaol superintendent John Hepburn. They all knew Booth, due to return the following day, would be most displeased. ‘No one provokes me with immunity’ was his regimental motto, and a murderous attack on an overseer was severe provocation, and he would be determined the culprit, or culprits, be immediately identified and punished.

Rushing to the gaol yard the three officers passed McGuire being carried away by convict overseers for medical attention at Port Arthur. They could see he had ‘a wound over his right ear, his arms … hanging down’ but he was still conscious, and none thought the wound necessarily fatal.

Captain Errington, who had only been Port Arthur’s regimental head for five months, immediately addressed the boys. He demanded to know who had struck McGuire and threatened that if the guilty boy or boys did not come forward, he would take action against them all.

The sullen silence was broken. But not by Charles Campbell, who had alerted Rose to the attack. It was Henry Sparkes: ‘It was me that done it.’

Errington might have thought his decisive threat had delivered his culprit, but gaol superintendent Hepburn knew the boys better, familiar with their propensity for elevating status through bravado and ‘gameness’ or falsehoods. And he knew that threatening to punish all if a culprit was not identified was a well-tried but mostly unsuccessful tactic, boys refusing to reveal the guilty and silently accepting punishment rather than inform on others in an unacceptable ‘dog’ act, even when they themselves were innocent.

And as Inspector Horne had recently detailed, the boys’ code was to tell as many lies as was necessary for oneself, or for the whole fraternity.

Hepburn looked at Sparkes, who recently had twenty days in solitary and thirty stripes for ‘misconduct’ and being ‘absent without leave’. He was a likely candidate, perhaps angry that McGuire had caused his most severe thrashing, or perhaps that the overseer was about to report him for another offence. But Hepburn knew boys did not admit to any wrongdoing, even of relatively minor offences, so perhaps Sparkes was falsely claiming to be the culprit to gain some status or had been intimidated by bigger and older boys. Hepburn told the boys he would not take Sparkes’ statement as the truth, or take anyone else at his word, unless others came forward to verify it.

With blood and unanswered questions in the air, Captain Errington left to see if McGuire could reveal who had struck him.

The overseer was conscious enough to relate that he had been standing between the two gaol yards separating larger and smaller boys. A boy named White was near him, he said, but he couldn’t say if he had struck him, and yes, the boys Campbell and Sparkes were standing near him, but he had ‘no quarrel’ with them and had not made any threat to take them before the magistrate. ‘I cannot swear by whom the blow was inflicted,’ he told Errington.

By week’s end, on the last day of June, McGuire succumbed, ‘Died at Port Arthur of fracture’ noted on his record. Those running Point Puer were now confronted with the hard truth that boys were capable of much more than mischief, insolence, profanity, misconduct and ‘crowning’ of overseers. One or more of them was so wicked as to be capable of a murderous attack. The body of Hugh McGuire was the proof.

• This is an edited extract from The Lost Boys of Mr Dickens by Steve Harris, published by Melbourne Books and available now.

Originally published as 18 child convicts, one body and a dubious confession