Andrew Rule: Welcome to South Australia and the edge of darkness

When a skeleton was found in a South Australian town and was matched with a skull found years ago, it added to the state’s long list of grisly stories, writes Andrew Rule.

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There’s the Beaumont children and “the Family” and the two little girls who vanished from a football game. And the Truro murders and the “baby in the suitcase”.

Now there’s the Terowie skull case, latest in a long line of South Australia’s horror stories.

Terowie isn’t much, somewhere a traveller would rather not stop on the road to nowhere. But it is up there with Snowtown as the spookiest place in Australia.

Both are in the Mid-North of the state, the badlands where the rain runs out as fast as the dole payments.

Its rundown cottages were built in a burst of optimism back in the 1870s after a couple of unusually wet years misled settlers into thinking they could survive beyond Goyder’s Line.

The settlers moved on but the brick and stone buildings they left behind now attract people drawn to low-rent prices and maybe to the semi-lawlessness that isolation brings. The perfect set for a film about the end of the world.

Walk down the street in Terowie and you see a boarded-up house with an ominous sign daubed on the door: “BOOF WAS POISONED BY 1080 BAIT 2005.”

Boof being a dog, probably a sheep killer, and 1080 being the poison farmers use to kill vermin. It seems 2005 was a bad year. It was when a local man vanished.

Not that anyone seemed to care about Martin Meffert’s whereabouts. The few who knew the 23-year-old battler weren’t saying much. But there were hints that the truth was more sinister than suggestions he had drifted interstate after the last known sighting of him at an Adelaide bus stop in February that year.

Finally, in 2013, police pulled a skull out of a chimney in a Terowie house owned by a relative of the missing man. That tended to cast suspicion on the motley crew who had hung around with Meffert eight years earlier.

Oddly, the rest of Meffert’s skeleton would stay missing another six years — until last week, when his lonely bones were finally dug up behind the house and reunited with the skull in a forensic lab.

Justice moves slowly. It wasn’t until 2017 that South Australian police revealed that someone had for eight years drawn cash from Meffert’s bank account, draining it as Centrelink welfare payments came in.

The cash wasn’t being drawn interstate but just down the road, mostly at a service station and at ATMs at Peterborough and Jamestown, both within easy driving distance. It seems that whoever had hidden Meffert’s skull in the chimney was milking his pension money close to home.

When detectives finally arrested a 30-year-old Terowie man last September and charged him with murdering Meffert, the accused’s name was swiftly suppressed because he had been only 16 at the time of his alleged crime.

A court will decide his guilt or innocence but the case shares something with the Snowtown “bodies in the barrels” murders and the Wynarka “baby in the suitcase” outrage, in which a toddler and her mother were killed separately in two states.

In each case, the killers were motivated by “milking” the murder victims’ bank accounts, which were automatically topped up by an efficient but obviously blind government department.

The “baby” in the suitcase was Khandalyce Stevenson, a toddler who’d vanished with her young mother Karlie Pearce-Stevenson in 2008. It was only after police linked the child’s remains (found at Wynarka) with bones found in the Belanglo forest in NSW that they arrested Daniel James Holdom, now serving time for both murders.

Holdom and others had stolen $90,000 in benefits from Karlie’s bank accounts over seven years before his arrest.

In the Meffert case, more than $136,000 of disability pension money paid into his bank account was withdrawn in the eight years after his death.

A more intelligent crook might have gone interstate to withdraw money to create the illusion that Meffert was out there somewhere, but intelligence was not a feature of the crime. In fact, a court was told the accused was known to pull the skull out of a box as a “show-and-tell” to impress his mates and boasted of access to bank accounts.

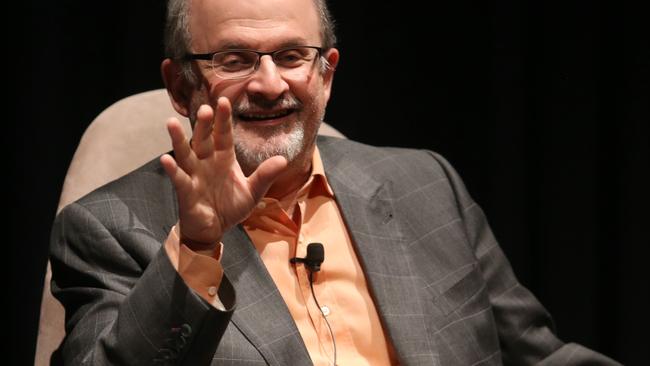

All this happened just two hours from Adelaide’s northern suburbs, a fact that might delight Salman Rushdie, the writer known best for spending decades in hiding after Islamic leaders declared a “fatwa” against him for his book The Satanic Verses.

In 1984, before his fatwa troubles, Rushdie was guest of honour at Adelaide’s first Writers’ Week. He made himself as popular as a Pollywaffle in a punchbowl by labelling the host city “the perfect setting for a Stephen King novel or horror film”.

“Adelaide,” he said, “is Amityville or Salem and things here go bump in the night.”

Rushdie has his critics, many of them armed and dangerous, but events in South Australia since then have rather proved his point about the state’s grisly history.

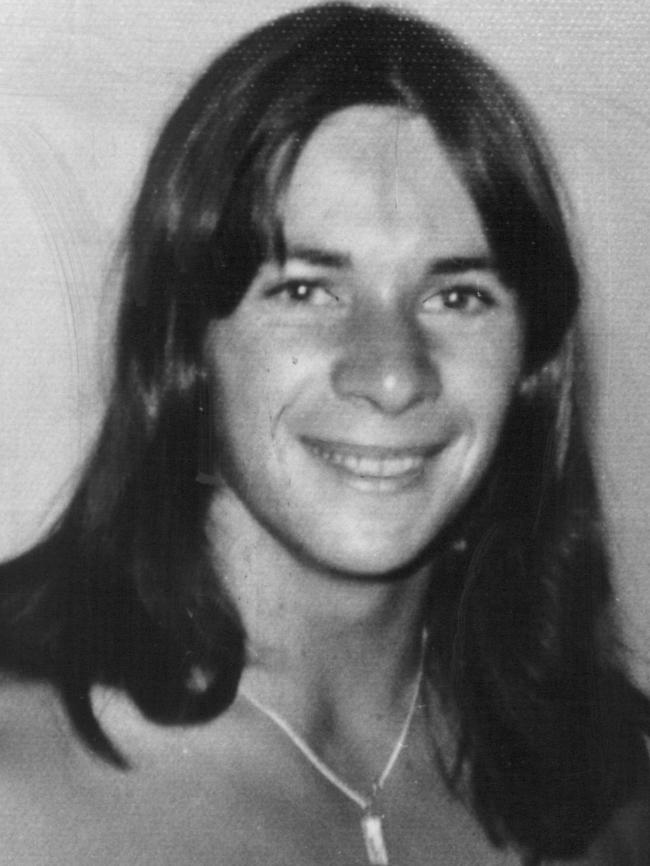

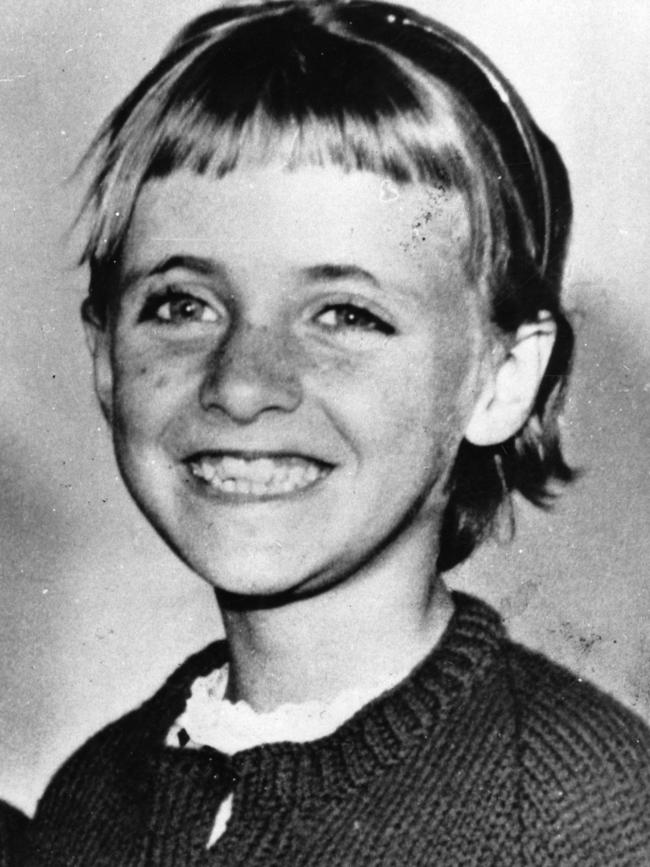

There was the abduction (and presumed murder) of Jane, Arnna and Grant Beaumont at Glenelg beach on Australia Day, 1966. Then the abduction of Kirste Gordon and Joanne Ratcliffe, who vanished from a football game at the Adelaide Oval in August, 1973.

There were “the Family” sex killings in the 1980s, for which only one man, Bevan Spencer von Einem, has been convicted despite rumours of a circle of deviates in high places.

There was the Truro horror: the abduction and murder of seven mostly teenage girls in two months over the summer of 1976-1977. It is now 40 years since one of the two men responsible, James Miller, was arrested for the murders in which he implicated his psychopathic accomplice, Christopher Worrall, who had fortunately been killed in a car crash in 1977.

The remains of five of Worrall’s seven victims were found near Truro, northeast of Adelaide.

When police chased fresh leads in 2015 about Kirste Gordon and Joanne Ratcliffe’s 1973 disappearance, they looked first at an underground bunker at an abandoned house at (outer suburban) Prospect. Then they searched two old wells on a remote country property at Yatina, in the Mid-North near Terowie.

Both properties were connected to Stanley Arthur Hart, who came under renewed suspicion after his death in 1999 because reporters revealed he had been a paedophile who routinely attended football at the Adelaide Oval.

The searches found no concrete evidence. But one of Hart’s family members recalls “Grandpa Stan” wearing a hat and coat to the football that matches the clothes seen by a witness who saw an older man dragging two girls away from the ground 46 years ago this month.

Further searches could be in order at Yatina, a stone’s throw from Terowie and Snowtown.

A Victorian who moved to the district recently tells us he is delighted with the old house he bought for $60,000 on a big block with its own orchard, cellar and shedding. But he is careful about some of his neighbours.

In a local pub one night he looked up to see a man pointing a gun at the ceiling while showing another drinker how to use it.

“It’s the wild west out here,” he says. “All sheep and lonely blokes … the edge of darkness.”