Sting in tail of departing La Nina climate driver

La Nina – which helped bring huge rains to Australia’s east – is over. But as it vanishes, another climate driver has begun messing with our weather.

La Nina has officially left the building.

The climate driver that has been largely responsible for a cool, wet summer over much of Australia, has – or is close to – dissipating, the Bureau of Meteorology has confirmed.

Its departure is around a month earlier than had been expected.

The once in a century rain event that soaked New South Wales and parts of Queensland, and led to three deaths, was likely its final push. It also led to one of the quietest bushfire seasons for years.

However, the Bureau has warned that while La Nina may have gone, another climate driver could still crank up the rain during the coming month and could lead to an uptick in tropical cyclones.

And there is good chance the La Nina could come back for an encore appearance after winter passes.

In a climate note, the BOM confirmed its El Nino – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) outlook had moved from La Nina to inactive. That means the climate driver is effectively in neutral – neither a La Nina nor an El Nino.

Other climate agencies have slightly different definitions of a La Nina – the US meteorological service still has a La Nina in place – but it is also likely to call an end to it in the coming weeks.

RELATED: In Australia, we’ve got our seasons all wrong

RELATED: Nino 3.4 – Pacific Ocean patch that could change Australia’s weather

The La Nina was called in September last year. And while it wasn’t hugely powerful in itself, it nonetheless led to some of the biggest weather impacts related to the climate driver for a decade.

Although the numbers around the 2020-21 La Nina have not yet fully been crunched, it’s likely March will have been one of the wettest on record in NSW.

La Niña has faded & the tropical Pacific Ocean has returned to a neutral El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) state.

— Bureau of Meteorology, Australia (@BOM_au) March 30, 2021

This doesn't mean the wet weather is over, some wetter weather may continue into April. Learn more about these climate drivers: https://t.co/67KlpxTubtpic.twitter.com/eto3pvjXxb

“This rain event was beyond what we were expecting,” Dr Ailie Gallant from the Monash University Climate Change Communication Research Hub told news.com.au.

“Ten years ago, in 2011, was a very strong La Nina. But this La Nina was very middle of the road, it wasn’t super weak or super strong.”

La Nina leads to quietest fire season for a decade

Today the NSW Rural Fire Service said it had been the quietest bushfire season since the strong La Nina year of 2010/11.

There were just 11 days of total fire bans in the state compared to 60 last year, said RFS commissioner Rob Rogers.

“Firefighters have responded to just over 5500 bush and grass fires burning 30,963 hectares across NSW, considerably less than the 11,400 fires and 5.5 million hectares lost last season.”

One of the factors that may have turbocharged this year’s relatively moderate La Nina was rising sea surface temperatures, often cited as a symptom of climate change.

Warmer water evaporates and heads into the atmosphere.

“A warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapour and scientists calculate that this can increase moisture in the atmosphere by approximately 7 per cent per degree of global warming,” said Dr Gallant.

What has changed for La Nina to be declared finished?

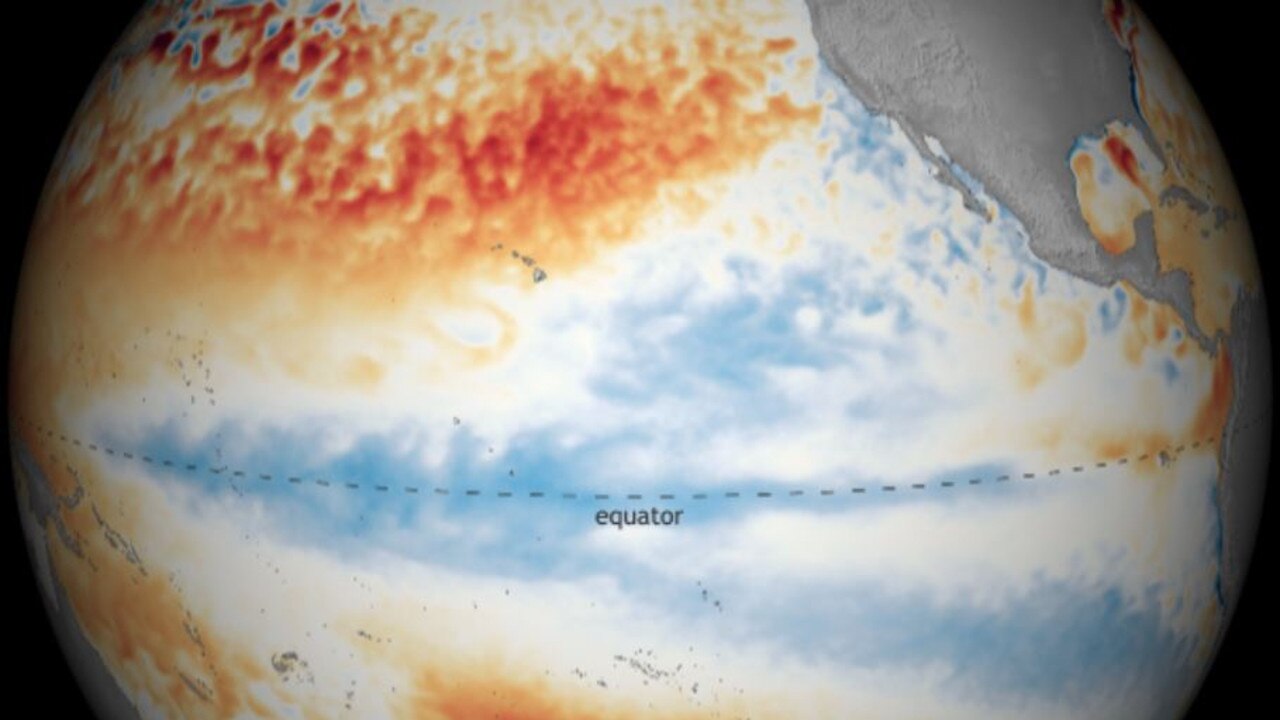

The cooling phase of the ENSO, a La Nina bubbles up when strong winds blow from east to west across the Pacific which drags cooler water up from the depths in the central and eastern equatorial ocean.

These winds then push warmer water off the coast of Australia closer to the continent which can bring more moisture.

But that’s all changed now, said the BOM

“Tropical Pacific Ocean sea surface temperatures have persisted at ENSO-neutral values for several weeks. Below the surface, much of the tropical Pacific is now at near average temperatures.”

La Ninas often decay during autumn but the expectation was it would likely linger, in a weakened form, until May.

Another climate driver now comes to fore

The BOM said the ENSO was now likely to remain in neutral until at least the end of winter. Neutral often means fairly average conditions across eastern Australia.

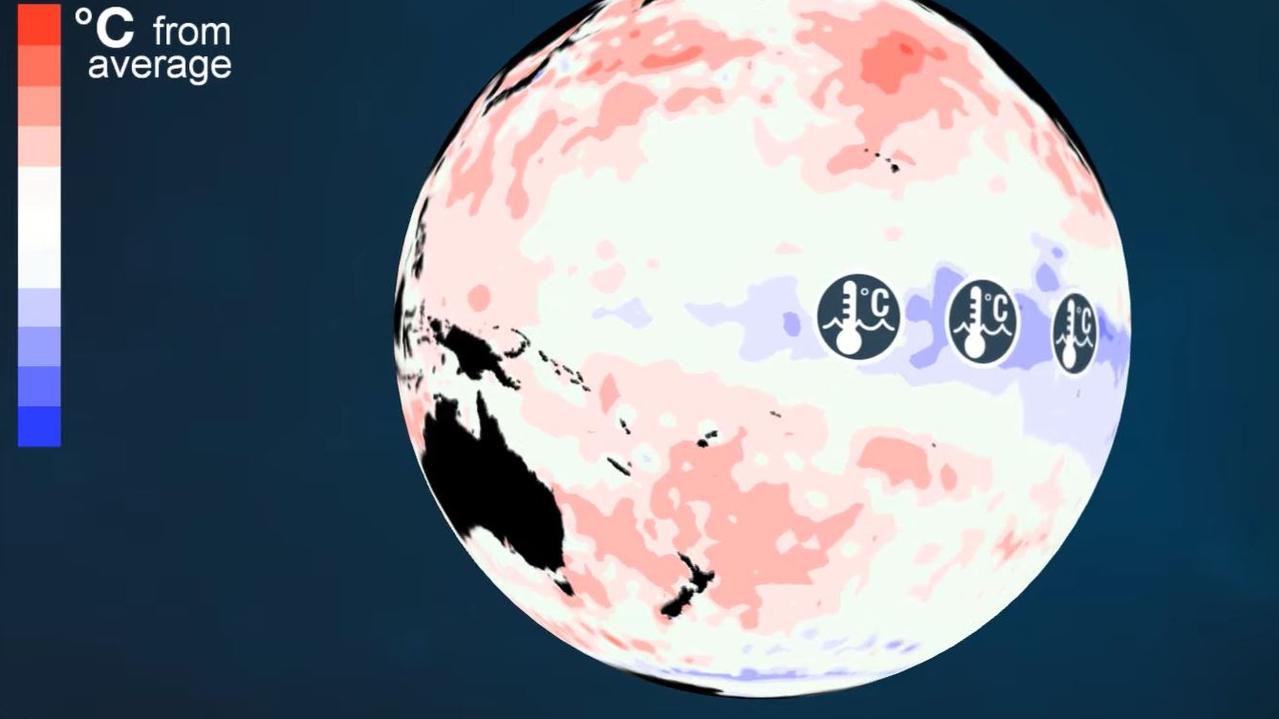

However, with La Nina departing, the influence of another climate driver has been beefed up.

That is the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO).

The MJO is a patch of cloud that circles the globe around the equator, including above northern Australia.

When it passes through, it can increase rainfall. Its effect is particularly strong from October to April when the Top End wet season is in full swing. When its visit to Australia combines with a monsoon trough – which is happening now – it can lead to even heavier rains and more cyclones.

Indeed, a tropical cyclone is a possibility over the coming days in the Indian Ocean close to north western Western Australia.

“The MJO has moved into the Australian region at moderate strength and is expected to bring increased cloudiness and rainfall to far northern Australia and the broader continent over the next week or two,” said the BOM.

Even though La Nina is fading away, the rain may not be. Some of those heavy downpours could feed their way further south during April.

La Nina could return

Like Hollywood hit movies, this La Nina could see a sequel. And, like most sequels, it probably won’t be a great as the original.

“There is a higher likelihood of having back-to-back La Ninas than a transition from a La Nina to an El Nino,” Monash University climate scientist Dr Shayne McGregor told news.com.au.

“On average, sea surface temperatures display a second cooling 12 months after a La Nina event. So it’s a double dipping but typically the second La Nina is smaller than the first.”

However, we’re now entering what’s known in climate circles as the “predictability barrier”, meaning it’s tricky to forecast what these drivers might do in the months ahead.

The fog lifts around June or July when we’ll know if La Nina is headed back, we’ll be stuck in neutral or if an El Nino is in the cards.

Originally published as Sting in tail of departing La Nina climate driver