Major events mogul Andrew Westacott’s last formula one Grand Prix

It will be the last time Westacott heads up Melbourne’s infamous Grand Prix as CEO. But what’s next for the major events mogul?

Sport

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sport. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Andrew Westacott understands the ups and downs of managing major events. That what is shiny gets dim. That what is new gets old.

Next week’s formula one Grand Prix will be his last as chief executive of the Australian Grand Prix Corporation.

Stan the Statistician, as some friends call Westacott for his eye for detail, will for the last time fuss over the coffee prices and loo hygiene, along with the logistics of a 45,000 seat temporary grand stand for what amounts to a pop-up city.

The event is cruising like never before. Race day tickets sold out in three hours. Melbourne has belatedly embraced the “imposed” spectacle, as Westacott calls it, of a supposedly foreign event. In an added bonus, the next local hope, driver Oscar Piastri, who grew up in Melbourne’s southeast, has landed.

These will be signature sign-offs of Westacott’s 12-year tenure.

“It’s never been brighter,” Westacott says of the certainty of Melbourne as a Grand Prix race host until 2037, and of a heightened acceptance for the Albert Park race, in part because Melbourne didn’t seem to know how much it cared about the event until the pandemic scuttled it.

Yet the Grand Prix hasn’t always glowed. Perennial mutterings over nebulous costs. Flagging attendances, in part because women didn’t much want to go.

Take the post-GFC years, when the event’s novelty had worn off, and the event needed to be reinvented with attractions for patrons who were not rusted-on revheads.

Or take 2020, the lowest moment in Melbourne’s Grand Prix history.

The Grand Prix gets cancelled

Westacott takes the first phone call in the grand ballroom at Government House.

The official F1 2020 welcome drinks are almost over; the throngs of very important people have migrated to the gardens outside.

The caller is his communications manager Haydn Lane. The news is encouraging. Of the nine F1-related Covid tests, eight have returned negative.

“What about the ninth?” Westacott asks.

“Yes, that’s what I think,” Lane replies.

He calls back about 20 minutes later. Westacott is alone in the ballroom now, seated beneath a portrait of Queen Elizabeth, who gazes down as he receives the news he does not want to hear.

“We’ve got the ninth test back,” Lane says. “It’s a positive – a McLaren mechanic.”

Some parts of this crisis have been well told; some not. Three years on, Westacott searches for the right word to describe the pandemic chaos, and lands on “crappy”.

For two weeks before the 2020 event, he had sounded buoyant. The Grand Prix will happen, he kept saying, albeit noting the European arrivals and their reluctance to shake hands.

British driver Lewis Hamilton said he was shocked to be here at all. Westacott was fully aware that the grand vision – the fast cars, the tens of millions of worldwide viewers – would be erased by a single positive Covid test.

And here it was – the night before the first day of F1 qualifying.

Some parts of this crisis have been well told; some not. Westacott whispered the revelation to his wife Tina, forced a smile for hurried farewells, then took the short drive to the meeting room at Albert Park’s Pit Building One.

A speaker phone sat in the middle of a board table. Chairs were strewn. Water bottles multiplied.

Calls flew between London, Paris, Crown Casino and F1 head Chase Carey, on his way from Vietnam. Westacott spoke with Victoria’s chief health officer, Brett Sutton. The what-ifs mounted. No decision would be made until the next morning.

Westacott got to his eastern suburbs home about 3am and flopped in bed for a couple of hours before returning to Albert Park.

Possibilities and contingencies swirl from 7am to 9am. McLaren abandoned its race plans. Soon, the same position would be reached by both F1 heads in London and Victoria’s health authorities.

The Grand Prix was to be cancelled. Westacott’s media buzzphrase of recent days – “all systems go” – came to haunt him.

The news was announced to race fans swarming outside a locked gate at Albert Park by a temporary F1 staffer, a burly policeman in tow.

Fans were displeased. “Where’s the CEO (Andrew) Westacott? Get him out here to explain this s--- to us.”

The footage would be played over and over for the next two years. Offstage, the Grand Prix corporation planned two more F1 races, and two MotoGPs, as well as a Phillip Island car festival. All were cancelled.

“I never like disappointing people, I never like disappointing fans, and that was a sad and unfortunate moment,” Westacott says of the gate scenes. “They were relentless days, and it just became a relentless couple of years.”

But is it world class?

Westacott has been a high-flying operator of Melbourne major events for almost two decades. He was operations manager for the 2006 Commonwealth Games before later taking over as Grand Prix head in 2011.

He won’t miss the crises of 2020 (the cancellation alone cost $37 million), or the disappointments of sponsors, suppliers and infrastructure providers who suffered for the uncertainty.

But he will miss other aspects of the job. Such as the overdue return of the race last year, when almost 420,000 people turned up, many to be greeted by Ricki-Lee Coulter belting out Aussie anthems at the gate.

The race-day mood spoke of something between a picnic and a nightclub. “We reinvented many of the facilities and activities around the venue,” Westacott says of the enforced two-year lay-off. “We got some things done that we weren’t able to get done in the past. There were some silver linings.”

Westacott, 57, is all consumed in the months before the race. He is a details person, which he blames on his chemical engineering background. He can recite minor asides about this or that event from decades ago.

The same intensity explains his fondness for cooking. When Westacott argues that paella must have chorizo, you just know he has considered the question deeply.

He lists tenacity, pragmatism, more tenacity and realism as key attributes for the F1 job. He appreciates that the quality of the drinks on offer can matter as much to race day fans as the view from the Brabham Grandstand.

“There’s a lot of moving parts,” he says. “It’s a combination of a Meccano set, a game of snakes and ladders, a bit of Mousetrap, and maybe with Bernie Ecclestone back in the day, a little bit of smoke and mirrors, too.”

Lean times followed the global financial crisis of 15 years ago, when in race terms “not terribly much was happening”. Westacott felt the event needed to be pitched as a four-day festival.

As he puts it, he tried to inject a little Moomba, a bit of royal show, a kind of food celebration, and an awful lot of car race, under the watchful eye of then chairman, the late Ron Walker, whose catchphrase question – “But is it world class?” – still echoes at Albert Park.

Australian Open officials tread a similar path to reinvigorate the tennis tournament. Major events, the thinking went, now had to appeal to fans who didn’t already go. “The measure was to make it a broader entertainment offering to grow the interest beyond core F-1 fans,” Westacott says. “And it worked.”

Perhaps 450,000 fans will stream through the gates over the four days next weekend, almost 40 per cent more than in 2019. Many will be newer fans, perhaps inspired by the lockdown TV hit, Drive to Survive, who can trust in the prospect of the annual event for another 15 years, pandemics notwithstanding.

I’ve got to keep moving

Westacott’s resignation ends an association with Albert Park dating to childhood. He did school cross country races there. He went to kids’ birthdays.

He describes Melbourne sports fans as unique. You cannot “con” them, he says. They know – and judge – whether all the parts, large and minor, contribute to a pleasing experience.

“I think they’re more demanding,” Westacott says of local fans. “I wouldn’t say we’re more passionate than the Italian fans at Monza or US sports fans. But we’re definitely more demanding. It’s not just the big glossy things, but also the things that journos don’t write about, such as the safety of the track, the viewing, the public transport, and so on.”

Westacott is informed by his own childhood experiences. As a kid, he would catch the train to Kooyong to watch the Australian Open. He would sit at the MCG, one of a few hundred fans, and absorb Sheffield Shield games.

His father John played VFL footy for Footscray, before many years as a golf official and tournament marshal. His son tagged along.

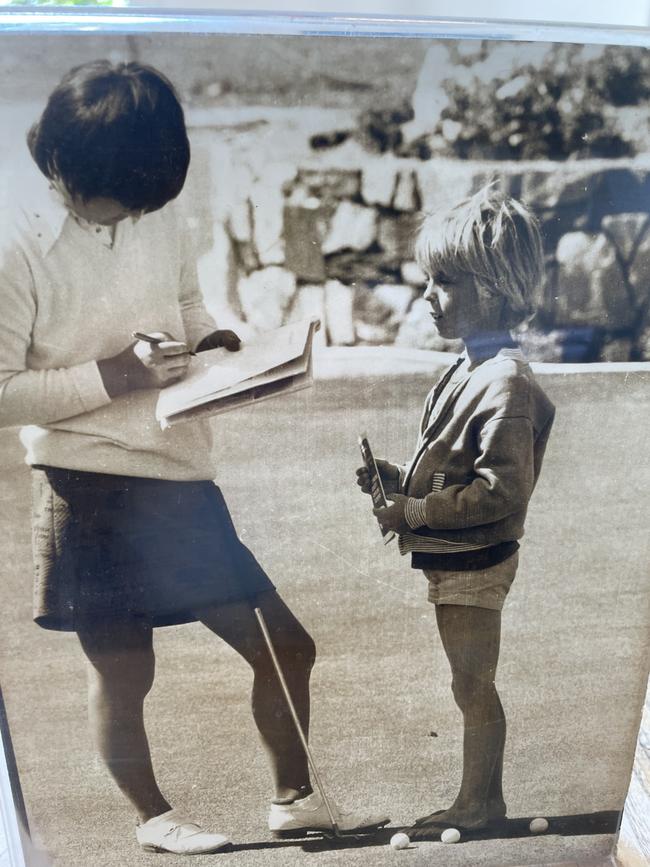

Westacott would get autographs. A photo of him with golfer “Chako” Higuchi sits in his Glen Iris living room. Westacott, who was nine at the time, remembers the day well – he was later told off for wearing thongs on course.

A photo of that phone call for the positive test in the governor’s ballroom is mounted in a frame in the study. Under the house, curated boxes of memorabilia – AFL records, lanyards, invitations – attest to a lifetime passion.

He has pieces of the 2006 Commonwealth Games athletics track there. Uniforms. Bunting. Westacott readily agrees with his wife Tina. He’s a “hoarder”.

On air not long ago, fielding loaded questions, Westacott good-naturedly put his hand up for Gill McLachlan’s AFL head role.

But there would be many prospective places for him in that sweet spot of the Melbourne major event approach, ignited more than 30 years ago, which has since been imitated elsewhere.

“I finish on June 30,” he says. “On July 1 I’ll probably walk out and say, ‘well, what am I going to do today’? But I’m a bit like a car. I’ve got to keep moving.”