Sacked podcast 2022: Robert Shaw’s sometimes painful love affair with footy

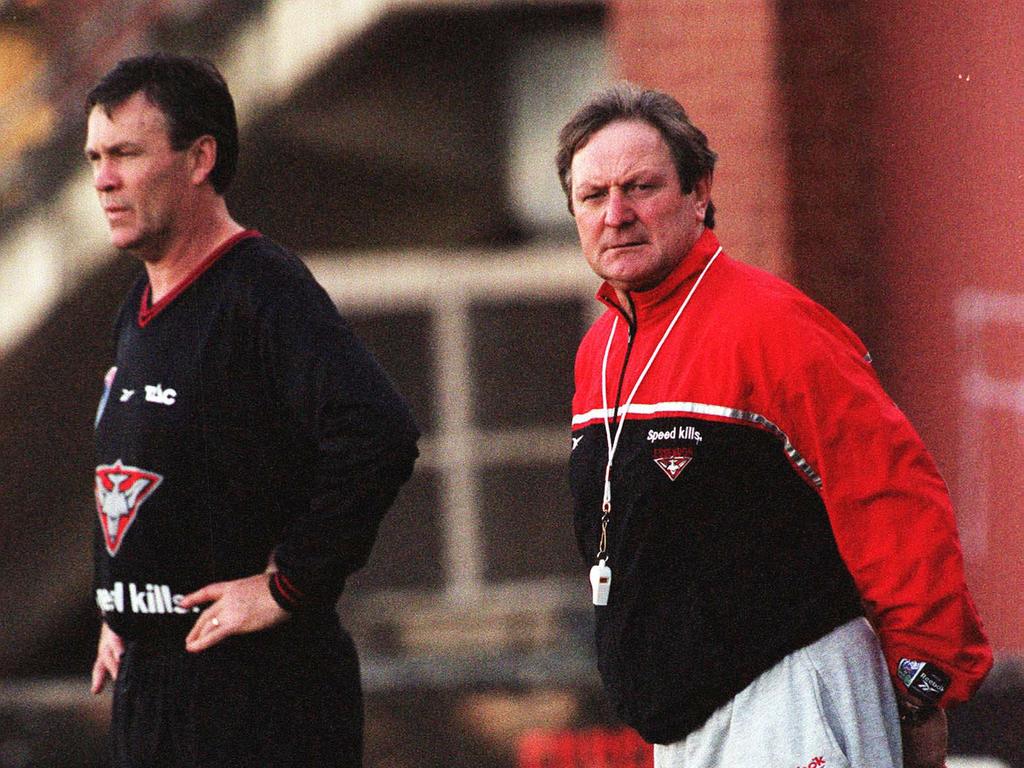

The vultures were circling Kevin Sheedy in 1998 when he phoned a trusted ally for help. This week’s SACKED podcast recalls how Essendon recovered and the pain of Fitzroy’s demise.

The intoxicating lure of football has always been impossible for Robert Shaw to ignore.

It’s been that way since he was an enthusiastic kid growing up in Tasmania with a voracious appetite for the game and its traditions.

At times football hasn’t appeared to have loved him as much as he loved it, but he’s grateful for what has happened on his journey.

His dodgy knees potentially cost him premiership glory as an Essendon player and stripped countless games off what should have been his overall tally.

As a coach, he revelled in his time at a cash-strapped but culture-rich Fitzroy … until the relentless strain almost broke him.

Then at Adelaide he endured the weight of coaching in a one-team town, before effectively sacking himself when the pressure affected his young family.

By 1998 he had returned to the relative tranquillity of his native state, content to spend more time with his kids and more time fishing.

Stream every match of every round of the 2022 Toyota AFL Premiership Season Live & Ad-Break Free In-Play on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-Days Free Now >

Then the lure irresistibly presented itself again … with a phone call from a familiar voice.

As Shaw recorded in the Herald Sun’s Sacked podcast, the conversation went something like this: “‘It’s Sheeds here’.”

“‘What do you want, Sheeds?’

“‘I am in a bit of trouble. They (Essendon’s board) are making a move against me and I think I am gone … you’ve got to come back’.”

“‘Mate, I have just sold my house. I am in Tassie. We are fishing. The kids are happy. My family is settled. We have a beautiful house in Hobart’.”

“‘No, you’re gonna come back. I’ve got Harvs (Mark Harvey), and we’ve got Terry (Daniher) and Bails (Dean Bailey). We’re putting the band back together.’”

It wasn’t quite a Beatles reformation, but by the end of this conversation, Shaw had rejoined the band and was on the move again. He agreed to return to Essendon as an assistant coach under Kevin Sheedy.

By the end of the next season, he had helped to take the Bombers through to a heartbreaking preliminary final loss.

By the end of the following year, Sheedy, Shaw and Essendon were celebrating one of the most remarkable seasons in the club’s history.

Only one loss came in that famous 2000 year – an 11-point loss in Round 21 to Western Bulldogs – which ruined a pact by the players to go through the season undefeated to avenge what happened in 1999.

Did they aim for the “perfect season”?

Shaw said: “It was driven (from the players) … and (James) Hird. ‘Let’s do something no one’s ever done’.”

“So credit to ‘Plough’ (Bulldogs coach Terry Wallace), they beat us fair and square (in Round 21).

“We were having a crack (at the perfect season) from Round 12. It’s still the greatest year ever played.”

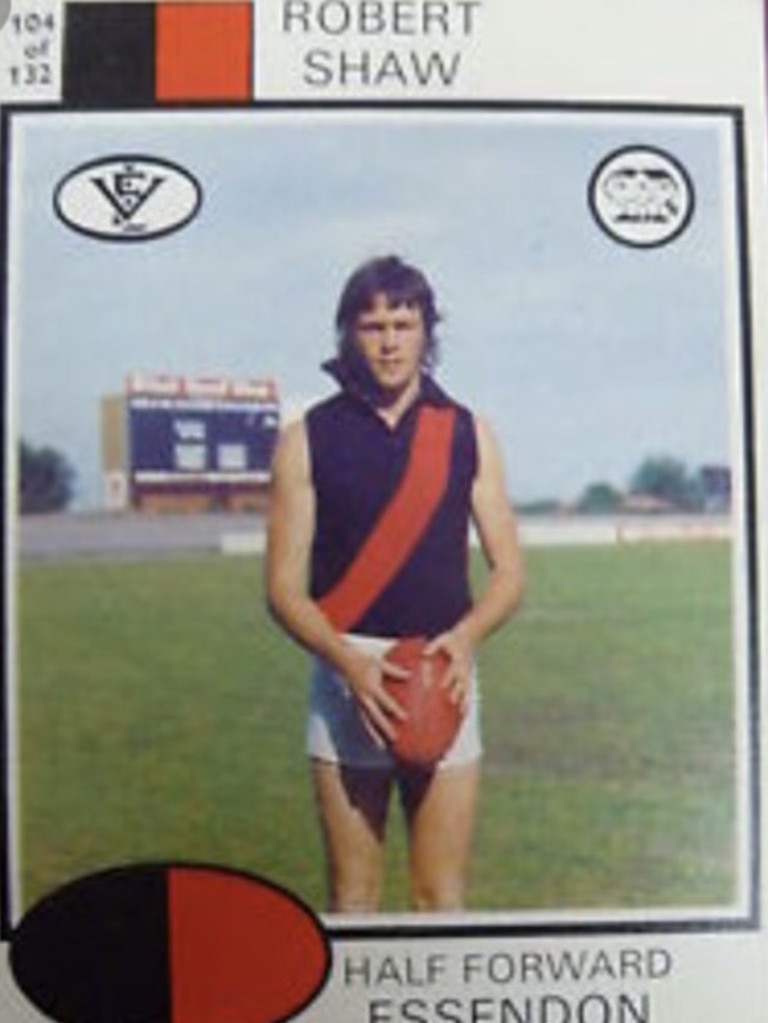

YOUNG BOMBER

Shaw was a teenage footballer from Sandy Bay when he was called out of class to the principal’s office in the early 1970s.

He wondered: “Did I belt someone at recess … I can’t remember doing that”.

Awaiting him were Essendon captain-coach Des Tuddenham and Bombers vice-president Jim Matthews, who wanted him to move to Melbourne.

Shaw made his VFL debut in 1974, finding out he had been selected via radio while attending the Essendon Drive-In with teammates Ron Andrews and Dean Hartigan.

The following year he played against Carlton – whom he had barracked for as a kid – lining up against his idols Percy Jones, Trevor Keogh, Barry Armstrong and Syd Jackson.

The Blues kicked 14 goals in the second quarter and won by 80 points.

At 7.30 the next morning, Tuddenham made his players crawl a lap of a near frozen Windy Hill.

“Tuddy said, “You didn’t go down on your hands and knees (in the game), you didn’t fight’. So he made us crawl in a single file a lap of Windy Hill on our hands and knees,” he said.

“There was ice on the ground. By the time I finished my lap, which took about an hour, I was bleeding from the palms of my hands and from my knees.”

KNEES

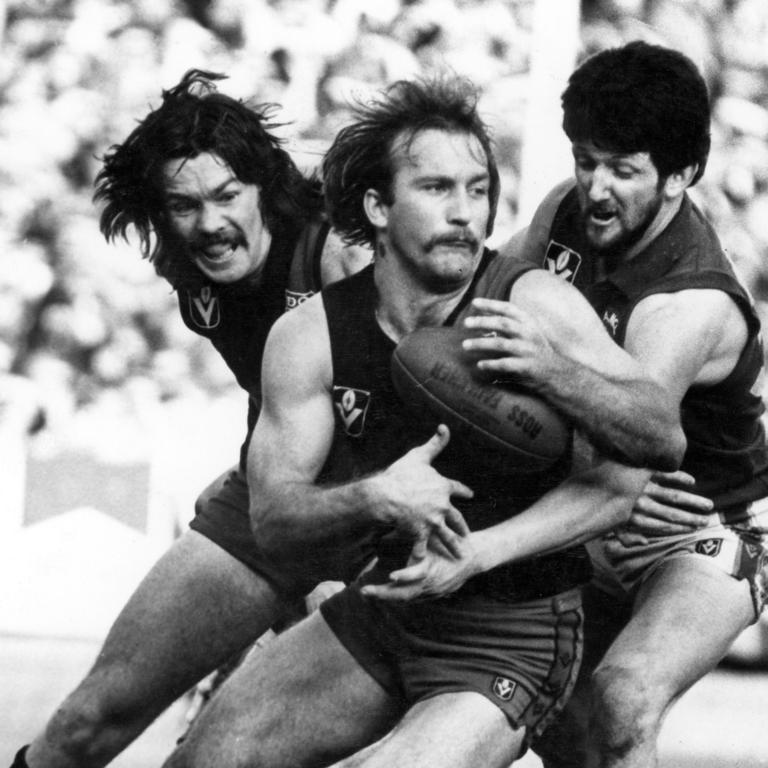

Shaw played 51 games in a career rudely interrupted by knee injuries.

“I had the old cartilage operation, which was significant back then. You would get a big cut down your knee and they would put it in plaster,” he recounted.

He played 23 games in his first five seasons before playing 16 in 1979. Five more games came in 1980 and seven in 1981, as well as in the club’s night premiership.

If it hadn’t been for his knees, Shaw may have played in the 1984 and ‘85 flags. He would have been 29 and 30. Instead, he had become Sheedy’s opposition analyst.

“I take a lot of confidence from the fact that when I was available my coaches played me.

“I have no regrets. I don’t say I missed that premiership, I don’t even think about it.

“I just loved my era.

“I bristle when I hear people say we are as bad (now) as the ‘70s. The ‘70s were a great time and we were only beaten because we weren’t good enough.

“You would get beaten, but we never lost our passion to play.”

Sheedy transformed the club and Shaw was happy to help out, saying: “All of a sudden I was building a bank of knowledge … it is where the coaching bug came in.”

FITZROY AND THE MERGER

Shaw became Fitzroy reserves coach, working alongside former Carlton star Rod Austin.

It provided him with “the greatest experience I have nearly had in football … we were fighting out of our weight divisions in certain areas.”.

He revelled in the never-say-die culture of the famous club who got by on the smell of an oily rag but was fuelled by an overwhelming sense of character.

Shaw coached the club’s last flag side, the 1989 reserves grand final win over Geelong. By the end of that year had a front-row seat to the proposed Fitzroy-Footscray merger.

“Curly’ (Austin) was going to be the coach and it was going to be the Fitzroy Bulldogs … a merging of the two teams that had a slant towards Fitzroy,” he said.

“We went to an extraordinary meeting … I was standing there and in walks (Bulldog greats) Ted Whitten and Charlie Sutton. I am about five metres to the left of them and I will take this to my grave, Ted has turned to Charlie and said ‘I think we’re f---ed mate.”

But people power saved the Dogs, scuttling the merger and putting Fitzroy under more heat.

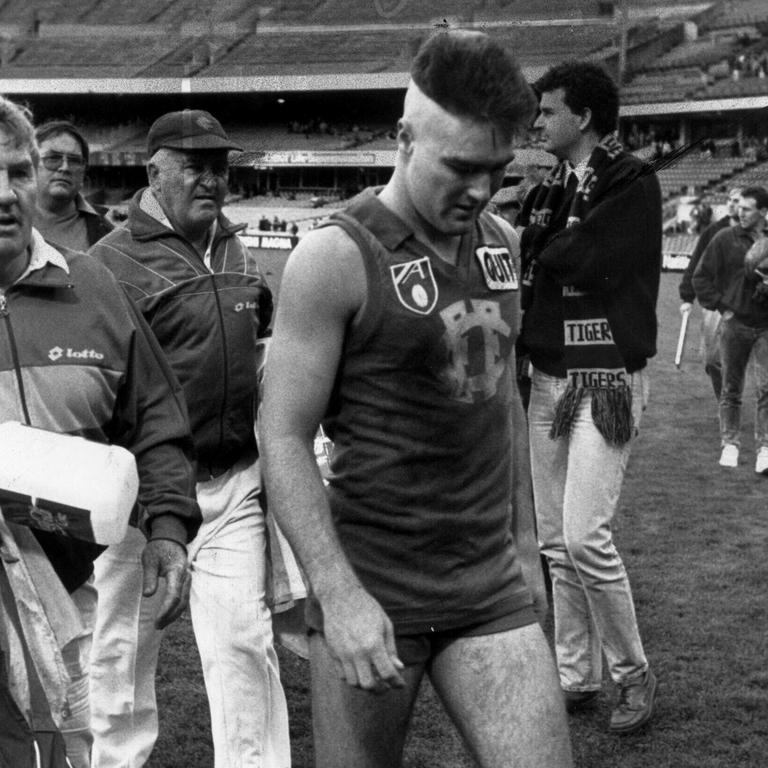

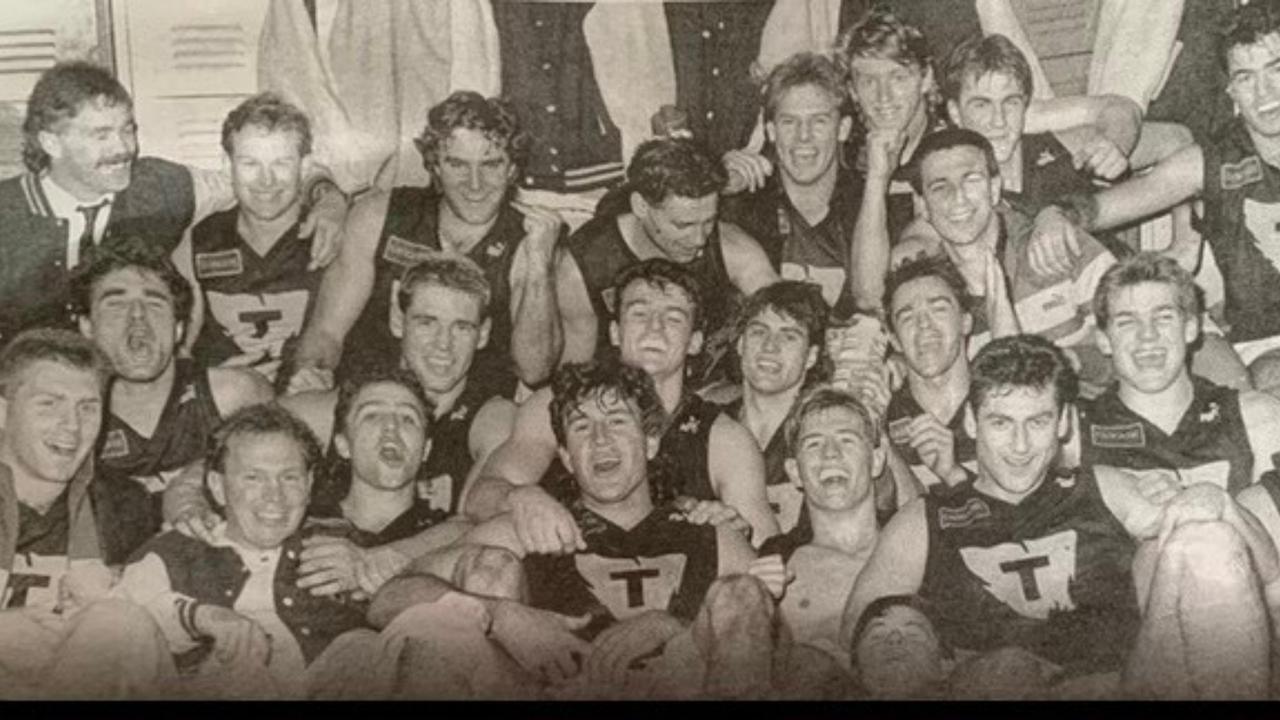

@theheraldsun #25 Coach Robert Shaw & Fitzroy players after a defeat by the Eagles in Perth 1994 pic.twitter.com/2V74jhZXxf

— Wayne Ludbey (@WLudbey) October 13, 2015

‘THEY WERE ALWAYS COMING FOR US’

Shaw took over as Fitzroy’s senior coach in 1991, and while they didn’t play finals in his four seasons, they often proved giant killers.

“I wanted to win, I wanted to compete, I was intense, I was strongly focused, all these sorts of things are a strength, but they are also a major weakness,” he said.

“We had two great years in ’92 and ’93, we had a team on the verge, but they (rival clubs) were always coming. Collingwood were always coming at (Paul) Roos. Brisbane was always coming at (Alastair) Lynch, there was always this undercurrent that they were coming for us.”

One of his favourites was cult hero Darren ‘Doc’ Wheildon, an explosive but enigmatic forward who Shaw desperately wanted to see reach the greatest of heights.

“Let’s talk football; let’s forget about the haircuts and the indiscretions; if we just focus on the footy … Doc was extraordinary.

“It raised eyebrows with other players who were far more dedicated. If Doc did something wrong I covered it; if he missed a Sunday morning training I told the players he was crook and had rung me. I had never wanted a young man to make it as much as I wanted Doc to. He came from a hard upbringing, and football was going to be his life.”

It never quite panned out, but Shaw remains in touch with Wheildon as he does with many of the players he coached.

The battle against the odds at Fitzroy finally got to Shaw late in 1994.

“The constant (battle) broke me, that’s why I cannot speak highly enough of all the players I coached there, it never broke them,” he said.

“I just came home one day and said to my wife, ‘That will do me’.”

Shaw wishes he had stayed with Fitzroy to the end, with the club forced into a takeover fashioned as a merger two years after he quit.

“I would have liked to have led the fight and gone down swinging,” he said.

CROWS

By the time Fitzroy merged with Brisbane, Shaw was locked in his own battle at Adelaide.

He got a cold call from Crows CEO Bill Sanders after leaving Fitzroy and pitched for the coaching job at a Hilton Hotel interview with Sanders and president Bob Hammond.

It was seen as the Crows pushing for a Victorian voice following the departure of inaugural coach Graham Cornes. Shaw says it was broader than that.

“They were looking for (a coach with) a little less connection with the playing group who could make decisions,” Shaw said.

“They (the players) had a lot of say in Cornesy leaving and they probably had a say in me leaving, but one of the things we were very clear on was to start the list development.”

In Shaw’s two seasons at the Crows, he brought through a host of young stars including Andrew McLeod and Tyson Edwards who would play huge roles in future success.

Shaw had to make tough decisions, including dropping Andrew Jarman and at one stage Tony Modra.

“Jars was interesting because when I got there they – and I am not going to name names- said ‘You have to get this bloke out of the club’.”

Shaw gave Jarman another chance. It worked for a time, but when he dropped him in 1996 for Edwards, it proved to be the end for the SA footy great.

SACKING

Shaw missed finals in two seasons as Adelaide coach, winning 17 of 44 matches in 1995/96.

“I wasn’t hopeless … but I didn’t get them into finals,” he said.

The 1996 season brought some difficult times, but Shaw stresses he and his young family loved the majority of their time in Adelaide, meeting many great friends.

“I want to reiterate it is a fantastic state and a fantastic footy state,” he said of Adelaide.

“But there were elements that affected me.”

Shaw could cope with the abuse of him as a coach under pressure, but not when it affected his family.

The Shaw family home had a security guard allocated to it for a period of time. “He was a good fella,” Shaw said of the guard.

There was also talk of a bomb threat and on one occasion manure was “smeared around my house … I was asleep. I have got a game that day and my wife must have got up and gone out and cleaned the house before I got up.”

It came to a head after the Crows were overrun by Melbourne.

Shaw was booed around the boundary line and was shocked when he got to the family area in the rooms and his own family wasn’t there.

“(I was like) ‘Where’s my family? I can’t find my family’,” Shaw said.

“Eventually we found them. The little ones are in tears; my wife was trying to hold it together.”

Shaw spoke to Sanders and organised a chat with the board.

He told them: ‘If you want to do it now, let’s do that … I will stand down. I haven’t worked (out) for you, and my family situation is unacceptable’.”

“They said ‘Go home and settle down’. And then I had a meeting with them and I said ‘Go and do what you have to do, go and look for a new coach’. That gave them the green light to start opening the batting with Malcolm (Blight).”

He coached out the season.

One day he sat his young kids down, telling them: ‘Dad’s lost his job … we’re leaving Adelaide, we’re going back home’.

His eldest daughter Kate brought a smile to his face, saying: ‘Dad, can we go back to Fitzroy?’

TASSIE, FOOTY, FAMILY TIES

Loyalty, commitment and passion are a part of Shaw’s DNA.

He is still driven by the love of his family, the connection to his native and adopted states, and the rich history of Australian football.

When Shaw coached the Tasmanian state team in the early 1990s, he eloquently stated the case why the state deserved its own AFL team.

He finds it hard to believe that a generation on, it is still being debated.

“I have flown the flag as a lot of people have flown the flag,” he said. “We have spent 30 years of our lives pushing it and getting into trouble and agitating for it.”

He stressed the AFL cannot continue to “dismiss a cultural heartland”. A new team could be Gillon McLachlan’s parting gift to the game.

As far as family goes, he has expressed his faith in his nephew Tim Paine, who resigned as Australian cricket captain in November after being involved in a text message controversy.

“He had a bad hour or so in his life,” Shaw said of Paine. “His fightback from a career-threatening injury to be the top wicketkeeper in the game and lead his country was an inspiration. Of course, I stand by him.”

Shaw, who still teaches and is a co-hosts the Footyology podcast, knows he has more to give to the game.

A meeting with Mark Williams late last year – who had been overlooked for AFL jobs in recent years before re-emerging as part of the Demons’ drought-breaking flag coaching panel last season – has buoyed Shaw.

He says knowledge, experience and a feel for the game are far more important in a CV than a number on your birth certificate.

“I was so happy for Choco (Williams), We had the greatest chat and compared notes,” he said. “He said to me, ‘Keep going’.”

Anyone who knows Shaw, or knows his extraordinary journey, has no doubt that he will.

THE ‘CHOKE JOB’

Shaw says the Bombers’ crushing 1999 preliminary final loss to Carlton was not a “choke” job despite its reputation as one of footy’s greatest upsets.

But Shaw admits Essendon’s coaches’ box was distracted by Lance Whitnall’s dangerous impact on the game until it was too late as Anthony Koutoufides tore the game away from the Bombers.

In a compelling examination of that second half for the Herald Sun’s Sacked podcast, Shaw says he was directly responsible for assessing match-ups and Carlton’s tactics during the epic contest.

Essendon was up by 11 points at three-quarter time but despite kicking the first goal of the final term was run down in a one-point loss as Fraser Brown stopped Dean Wallis’ last attacking thrust with a frenzied tackle.

Koutoufides’ 10-possession, six-mark, two-goal last term was described by former Blues captain Stephen Kernahan as “the greatest quarter of football ever played”.

Yet despite the nature of the loss, Shaw told Sacked that the battered 18-win minor premier did not choke against a 12-win Carlton side.

“I’m not as upset with that. And I don’t write it off as an extraordinary upset. People won’t agree,” he told Sacked.

“Because people on social media still say what’s your worst moment in football? ‘99? Okay, I’ll tell you something: We’d come off a very low base, the marshmallows. We’re a pretty soft team.

“We changed a lot of things, toughened the team up. Got some players into the team.

“And people don’t forget. You go into any game without Scott Lucas, Jason Johnson and James Hird at their best (and out injured you are in trouble) and our depth was a bit light.

“We were building and everything was working but I’m very philosophical.

“I refute choke and I refute any disrespect to Carlton.”

Carlton jumped from the blocks with Whitnall kicking an early goal and setting up three more in a hot start to the game. Koutoufides was far from Essendon’s chief concern.

“It’s all about Kouta but up until three quarter time, he is controllable,” says Shaw.

“If you look at his stats, not bad. Whitnall was our biggest problem. Camporeale too.

“They are coached by (David) Parkin and they are a very proud club and they get out of the blocks.

“Our third quarter we kicked seven goals eight (behinds) and if we kicked straight we would have stretched the lead to four or five goals and we would have hung on. We kept giving them a sniff. Whitnall would kick a crucial goal, Justin Murphy had a great game and Carlton was a bloody good side.”

As the last quarter started Koutoufides had been kept to only 19 possessions and no massive influence and Essendon’s early last-quarter goal had arch rival Carlton in control.

Then things got ugly as Koutoufides ran rampant.

“The Koutoufides effect. He starts the last quarter in the centre bounce,” recalls Shaw.

“Anyway, we have controlled him with (Justin) Blumfield and (Chris) Heffernan. Then Parko does the (Jake) Stringer thing with him. Starts every centre bounce, drifts forward. And it’s my job to monitor the opposition.

“I had nothing to do in the coaches box with Essendon except watch the opposition, tell Sheeds what they are doing. And I am getting lost in a final, even with my experience.

“Kouta takes the centre bounce, drifts forward. Who has got him?

“Do you want Blumfield to go with him? At one stage he has Michael Long. That’s a mismatch.

“Then he goes to the square and marks and kicks a goal. Who is on him, Shawy?

“Well our centre bounce is Blumfield, (Joe) Misiti, Caracella. They are not great match-ups.

“You don’t have a match-up for a guy six foot four (193cm) who can play centre square and go to full forward.

“So I lost him in (terms of) who is picking him up. Then we said, ‘If he goes forward Dustin Fletcher or Wallis has to take him’. But hang on, Whitnall is our main problem.

“Marc Mercuri had a kick that would have put us in front. And then Dean Wallis. And that’s it. I give Wally a big tick. Take them on. He’s trying to win the game. But he took on the wrong bloke. Fraser stood his ground and it’s become part of football and we lost by a point.

“But I refute choke.”