Few players had a football journey like John Barnes. From his brutal early days at Essendon to winning a fairytale premiership, he’s seen every high and low. He joins Sacked.

John Barnes was the ultimate bush scallywag, a mischievous kid raised in Kaniva before he moved with his parents to Cobram.

He once set fire to a school paddock, filled his dad’s FJ Holden with water instead of petrol, and put firecrackers in places they weren’t meant to be.

So when this carefree, high-leaping teenager was thrust into footy’s mid-1980s version of The Hunger Games – the brutal practice matches that formed a part of Essendon‘s pre-season under coach Kevin Sheedy – he didn’t know what had hit him … quite literally.

“‘Sheeds’ wasn’t the kind of bloke to cuddle you, unless you were going to go out and knock someone out,” Barnes told the Herald Sun’s Sacked podcast.

“Playing practice games at Cross Keys (Reserve) when you have got 80 blokes on the sidelines and he would say: ‘You are on now.’

“He would say – and these were his exact words – ‘If you survive this game you will be on the list for the 40 blokes I need to play … and you will have guys trying to kill you’.

“It was The Hunger Games.

“I thought if this is what life has to dish at me with league footy, let’s hope it doesn’t get any harder. Once you get two or three pre-seasons in, and they are punching on and kicking you, the rest is easy.”

Almost four decades on, Barnes can still almost feel the bone-on-bone crunches, the ruthless attack on the ball and often the man, and the long queue of players lining up to receive stitches from the club’s medico, Dr Bruce Reid.

It was the stuff of dreams or nightmares for young hopefuls, depending on how you fared.

Some survived, hardened by the experience.

Others wilted and were shown the door.

Barnes survived … just.

Throughout what proved to be a 15-season, 202-game AFL career which started with Essendon, moved to Geelong, and then finally back to the Bombers for a fairytale premiership, Barnes had to endure plenty.

Three broken jaws – at least one from a sickening behind-the-play incident – and more than eight serious concussions has convinced Barnes that his post-football battle with epilepsy and wild mood swings can be traced back to what he experienced on the field.

It has pushed him – and his family – to the brink in recent years.

Now 52, he is fighting to win a better deal for past players who have been changed forever by their AFL experience, but he remains as cheeky and combative as ever.

BOMBER TO CAT

NEXT month marks 35 years since 17-year-old Barnes made his league debut for the Bombers at Windy Hill – against Geelong, of all clubs.

He kicked four goals in the drawn game, polled two Brownlow Medal votes and was touted as the “next big thing” at Bomberland.

Five years and only 12 games later due to a series of injuries and a frustrating lack of opportunity, the blond-haired ruckman/forward was gone.

His complicated relationship with Sheedy might well have ended there.

“Sheeds said I didn’t have much respect, but the respect he was after I didn’t work out until I was in my 20s,” he said. “It took a while for it to sink in for me.

“I said ‘Man, f*** footy, I’ve had enough’. You know it’s politics and the bullsh*** that goes with it.

“There’s blokes (who were) getting a game who couldn’t play and I beat them all in the one-on-ones. I’m kicking five and six goals (in the reserves) and not getting a game.

“I was like, ‘Stick it up your arse, if he (Sheedy) wants more than that, I have got no more’.”

Barnes planned to go back home, play footy locally and live his life with a smile on his face.

Then Geelong came knocking.

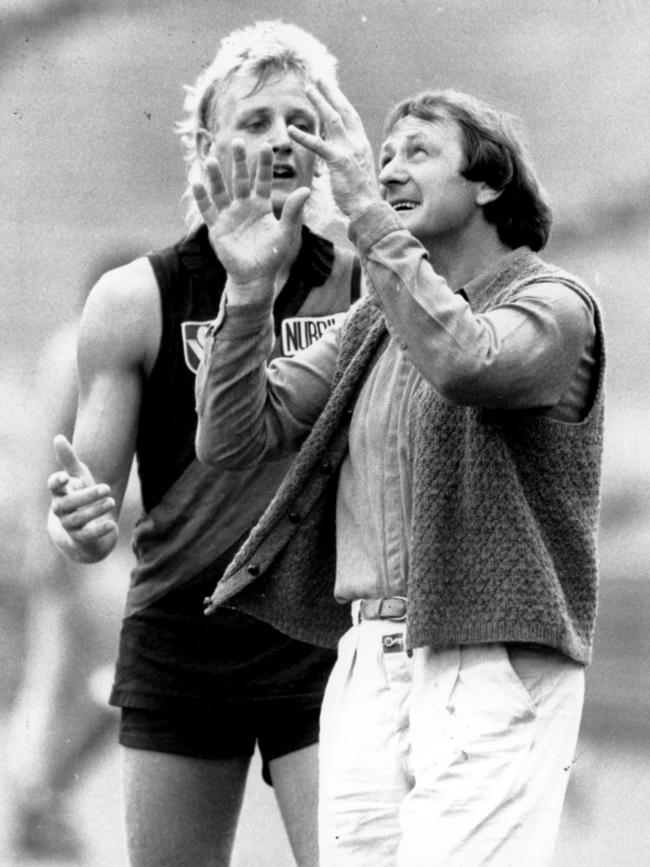

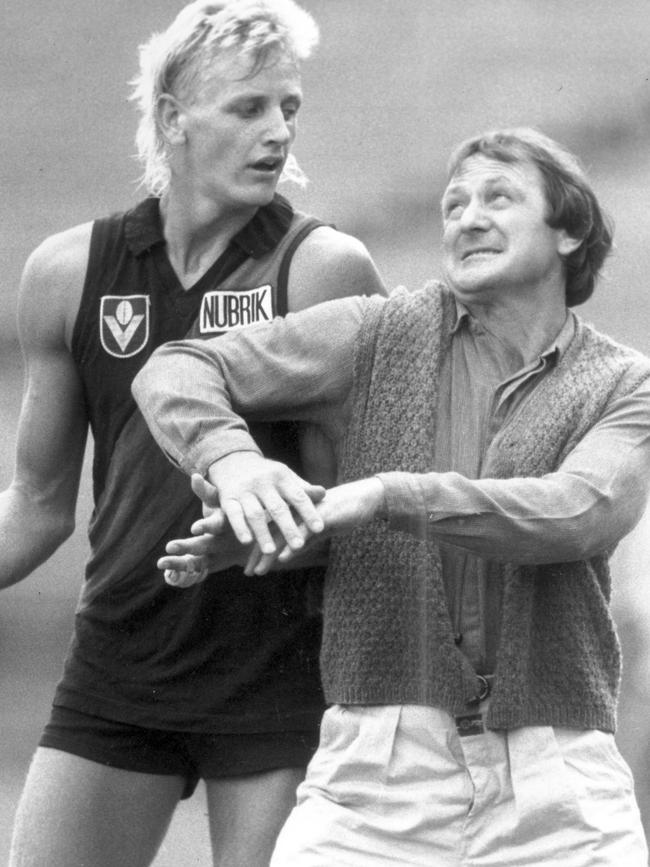

“So I went down and had a chat and ‘Blighty’ (Malcolm Blight) said, ‘I know what you can do. I want you to kick (on your) left foot and take hangers’. Sheeds used to say, ‘I don’t want you taking hangers’ and that was actually my biggest attribute.”

Barnes wavered for a moment, but a phone call from his Cobram mate Garry Hocking convinced him to keep his AFL dream alive.

Barnes’ dad also said: “Just have another go at it mate, you will always regret it if you don’t.”

GAZ AND BLIGHTY

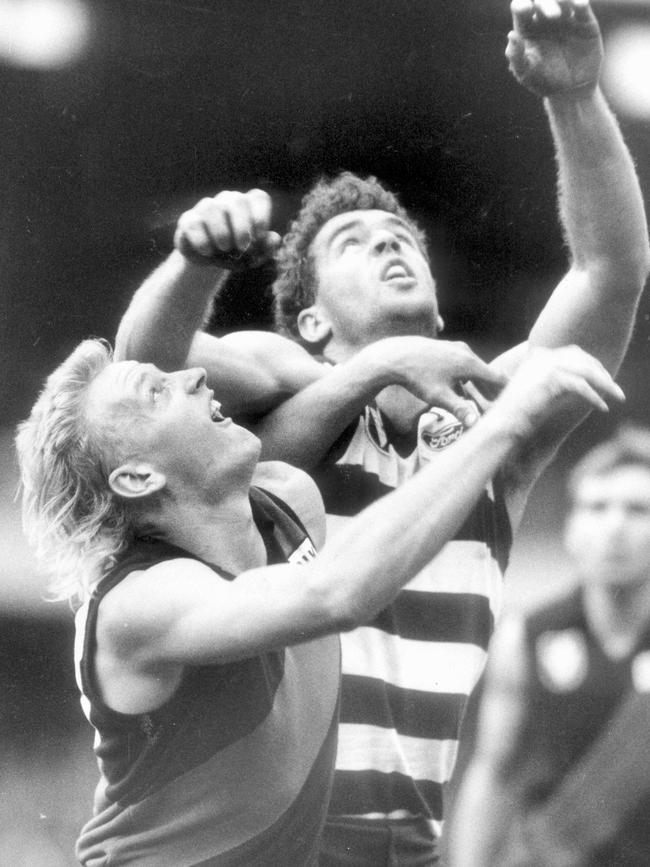

BLIGHT had a surprise test at Barnes’ first training session in the 1992 pre-season – a one-on-one pairing with the most powerful and gifted player in the game.

He would never forget it.

“We were down at Deakin Uni and it was my first session, and Blighty was always saying ‘Pair up, we are doing one-on-one,” Barnes said.

“The boys had run out. I think they knew what was coming. There was me and Gazza last. I went: ‘(I’m) John Barnes’ and he went ‘(I’m) Gary Ablett’.

“I said, ‘I think I know who you are, Gaz.’

“I (was) 95 kegs and he was the same, but built like a tank. You couldn’t move him. He was just freakish, but not very fit. He was the worst runner I’d ever seen, but once you got a footy in his hands … he just wouldn’t tire.

“I had front row seats and tickets that no one else had.”

Barnes thrived under Blight’s unusual, sometimes left-of-centre coaching style, moulding an individual’s strength into the way the team played.

He recalled the only time the coach had a crack at his best player.

“He told Gary Ablett off one time in a team meeting,” Barnes said.

“He was like, ‘There is a bloke here who won’t handball. There is a bloke here that won’t share the ball’. And I was thinking it could be one of 20 blokes.

“Then he goes, ‘That would be Gary Ablett’. He said: ‘Gaz, you will still kick 100 goals mate, but you have to f***ing handball’. The next week he gave three handballs and still kicked eight.”

THREE GRAND FINAL LOSSES

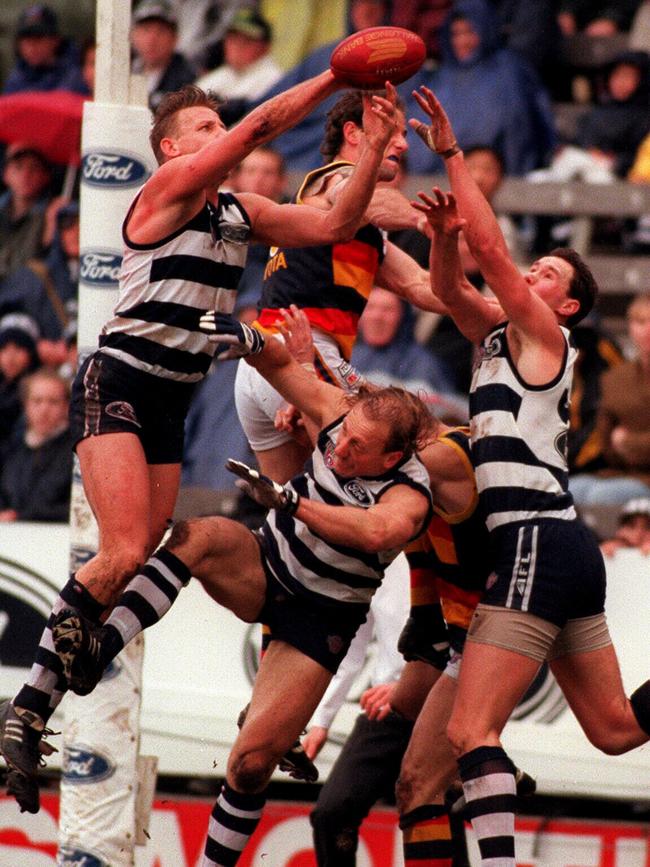

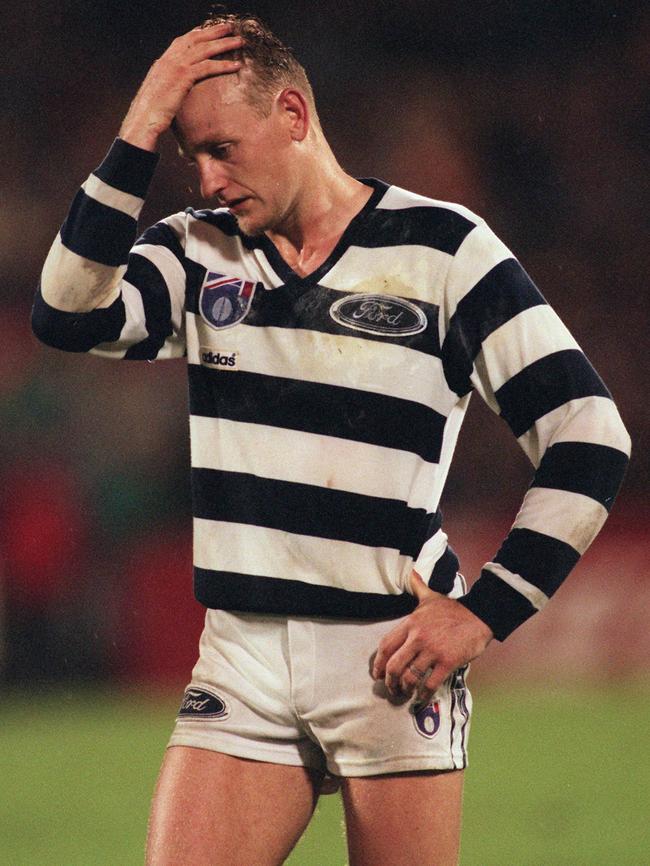

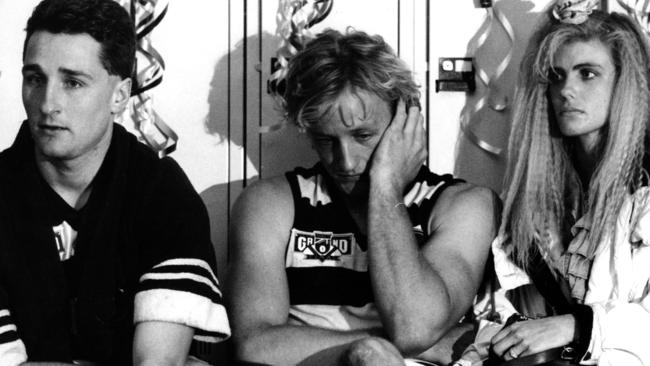

BARNES played in three grand finals losses with Geelong, but the pain of 1992 still sits with him.

“I think we should have won the first one (in 1992), but in the (next) two we didn’t have a hope in hell,” he said.

“We were 20-odd points in front (just before) halftime (against West Coast in 1992). Early in the third quarter Barry Stoneham ran in and kicked a point and 30 seconds later West Coast kicked a goal. If we had got that shot, it might have swayed the game our way.”

The final margin was 28 points.

It was a different story against the rampaging Eagles two seasons later – West Coast by 80 points.

Geelong may not have made it that far without a last-minute plan hatched by Barnes and Hocking in the dying seconds of the 1994 qualifying final.

The Bulldogs led by a point with 26 seconds left.

“Channel 7 don’t show the footage,” Barnes said. “Me and ‘Buddha’ are having a chat out in the middle of the ground. I said, ‘Buddha, Richard Osborne is going to come off the square and kill you’. He said: ‘If I get killed I don’t care, you just have to get the ball to me’.

“I went, ‘Done’. They all knew it was going to Buddha and I put it right down his throat, he got killed but he got a boot on the ball and David Mensch comes forward and takes a mark.

“He plays on and kicks the ball to Billy (Brownless).”

He added with a laugh: “I wish they had that footage to show how much work we put in instead of the bloke who says, ‘Look at me, I am the King of Geelong’.”

Brownless’ after-the-siren goal won the match and the Cats rolled on through the finals before being smashed in the title decider.

It was Blight’s last game as coach.

Gary Ayres replaced him the following year and the Cats made it through to the 1995 grand final but were no match for a relentless Carlton.

SACKED

BARNES’S fondness for a drink and larrikin attitude didn’t endear him to some people at Geelong.

But he says some of the rumours about him at the time were overblown.

“Did I like a beer? Hell yeah,” he said. “Did I go over the top with it? That’s up to the people who cast yourselves, like the media.

“They would go, ‘Barnesy is at it again. Oh poor form, Barnesy’s on the piss’. But nothing had changed for me. I would have two or three stubbies on a Thursday night.”

A contract impasse at the end of 1996 had some wondering if he could potentially be traded to Carlton, though he never spoke to another club at the time.

Then Cats president Ron Hovey asked one day how he was going with the contract. Barnes told him it was close.

Hovey went inside and emerged a few minutes later to say: “Your contract is ready, go upstairs and put pen to paper.”

“That contract was for ’97, ’98, ’99 … I pulled my finger out. I trained super hard, ate all the healthy food, and got super fit,” Barnes said.

“I think I had eight Brownlow votes up until round 6 or 7, then I broke my f***ing arm, and I said, ‘That’s it, I’m not getting super fit anymore if that’s what happens’.”

He was out of contract at the end of 1999 when former teammate Mark Thompson took over as Geelong coach.

“‘Bomber’ came over to the house and said, ‘Johnny, it’s out of my hands mate, you have to look elsewhere’,” Barnes said.

“I said, ‘Mate, you are the coach!’. He said: ‘Trust me, it’s out of my hands’.”

BACK IN RED AND BLACK

BARNES held out hope that Essendon might want him back, and he met Sheedy, the coach he believed had stymied his early career.

“I said, ‘Sheeds, are you going to pick me up?’ He said: ‘Yeah, we need another ruckman.’

“I said, ‘Are you going to put it in writing?’ and he said: ‘We don’t put anything in writing’.”

Barnes spent draft day at Leigh Colbert’s parents’ place at Eaglehawk, watching nervously on TV.

“The pick (40) comes up and Essendon goes … ‘David Hille, Dandenong Stingrays’. A ruckman? I have gone, ‘Sheeds is bullshitting me again’, so I have gone outside.

“Then Lynne (Colbert) comes out and says, ‘John, John, you’ve been picked’.”

The Bombers had selected Barnes with pick 59, resurrecting his premiership dream.

FINALLY, A FLAG

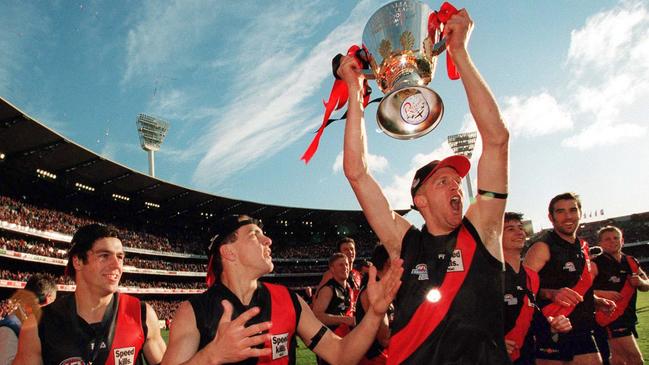

BARNES had played in eight grand finals for eight losses in all forms of footy leading into the 2000 season, but it would be the greatest year of his sporting life.

His laidback attitude mixed in with a greater maturity came at a time when the Bombers produced one of the most remarkable seasons in history.

“I just walked into a side that was going to win,” he said, noting how driven Essendon was in 2000 after its heartbreaking 1999 preliminary final loss.

“I thought, ‘These blokes are pretty switched on. I am pretty lucky here.’”

Barnes, then 31, played 24 games for the season, 23 of them wins, as the Bombers completely destroyed Melbourne in the grand final to break his premiership hoodoo.

“We just had everything, silk and hardness,” he said.

“This was like Santa had come to me and given me the present that I actually wanted instead of a train set and a bike and flat tennis balls, and all that sort of stuff.”

His premiership medal remains his most treasured footy memento.

“It is only a little round bit of tin, but it means you have accomplished something,” he said.

“I don’t have other trophies. I have no best and fairests at any level whatsoever. But I took a shitload of hangers. I kicked a few grouse goals.

“I have some great memories and I have got a premiership medal to put around my neck.”

He retired at the end of the following season, with his last game coming in the grand final loss to the Brisbane Lions.

GREATEST ACHIEVEMENT

POST-footy life hasn’t been easy for Barnes, due to his epilepsy and health challenges.

But the thing which has got him through the dark times has been the love and support of his wife, Rowena, and his family.

“They have been incredible,” he said.

Barnes is not easily given to emotion, but his voice falters when he talks about his wife.

“I met her when I was 17 and she was 16, it was 1986 or 1987,” he said. “You hear a lot of guys say it, but I have never put a girl through so much in all my life, and she is still here today. It brings a tear to my eyes. ”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

‘Mugshot’ in AFL dressing room causes stir

Fremantle has raised eyebrows with footage showing four mugshots posted up on the walls of the team’s dressing room on Saturday.

Trade guide: SuperCoach rookie rankings, cut-price guns

All of a sudden there are too many rookies available in SuperCoach. Who is the best option this week? Plus Callum Mills heads a tempting list of upgrade targets.