Adam Goodes documentary is confronting but everyone should watch it, writes Mark Robinson

It is haunting and shameful. It makes you wince. It’s makes you sad and angry. And it hurts. Did this really happen? How could this happen? We aren’t the Lucky Country, we are a country with an undeniable undercurrent of racism, writes Mark Robinson.

A documentary about the final stages of Adam Goodes' career and the abuse he endured is set to air tonight. In May of this year, Mark Robinson wrote this account of what people can expect.

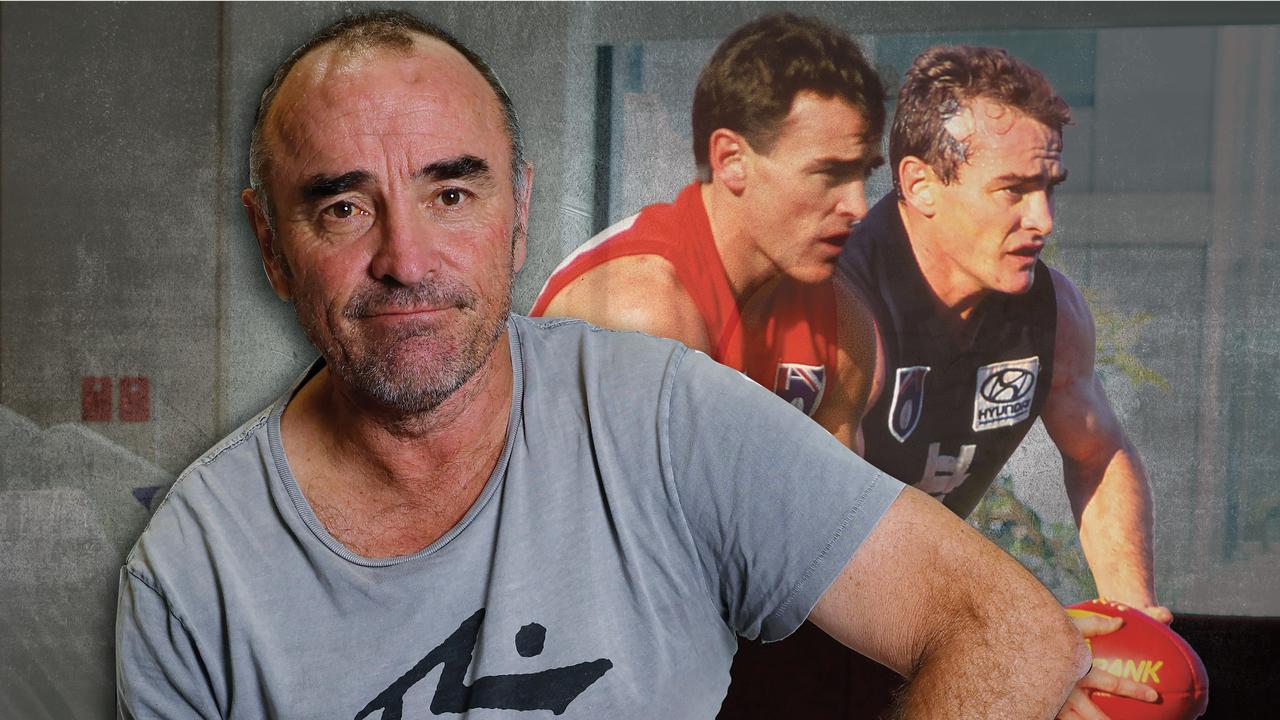

Michael O’Loughlin cried after watching.

He watched The Final Quarter with friends in January — before Goodes had watched it — and afterwards, as his friends shed tears, O’Loughlin tried to remain composed.

He had to be at a pre-planned function afterwards, so he quickly said his goodbyes.

“I just had to get out of there,’’ he said.

LEGACY LIVES ON: Players rally around Goodes

Distressed, he hailed a taxi outside of the Sydney studios of producer Ian Darling and flopped into the back seat.

“You know what, I just started crying and the cab driver turned around and asked me I was OK,’’ he said.

“I rang my mum in Adelaide and told her I had just watched an incredible documentary about our son, our mate, our brother, our blood and was crying.

“I was talking to her and my phone beeped and it was Goodesy.

“He was driving from Canberra and as we spoke, I just started crying again in the cab. I was trying to compose myself but it just so difficult.

“He’d probably call me a sook, but I’m quite happy to wear that as a badge of honour.

“What these things do is take you back to the time and place.’’

The time and place was Goodes’ final three years of his career, from 2013-2015, which was punctuated by a series of seminal events: the 13-year-old girl at the MCG, Eddie McGuire’s King Kong “slip of the tongue’’, Goodes being named Australian of the Year, the booing, the war dance, the ineptitude and confusion of the AFL and football in general, the booing and then, despite the pleas to stop, even more booing.

I watched the documentary on Thursday.

It is haunting and shameful. It makes you wince in parts. It’s makes you sad and angry. And it hurts in places.

When it was over, I didn’t have the tears of O’Loughlin, it was more like: Did this really happen? How could this happen?

Really, we aren’t the Lucky Country, we are a country with an undeniable undercurrent of racism.

Readers may disagree once they have seen it. Some readers may agree. But it should certainly be seen.

The Final Quarter is a collection of archival footage from football, current affair and morning TV shows, from radio interviews and articles from commentators across the country.

There’s no narrator to guide or influence, just news grab after news grab.

It leaves you to make up your own mind.

It leaves those in the documentary to see themselves in their own words.

Undoubtedly, there is confronting commentary.

Sydney mouthpiece Alan Jones was relentless with his character assassination of Goodes.

Again, you can judge for yourself when you see it. Personally, I hated it. And him.

Newscorp writers Andrew Bolt and Miranda Devine were also condemning in their commentary after Goodes was named Australian of the Year. I hated that, too.

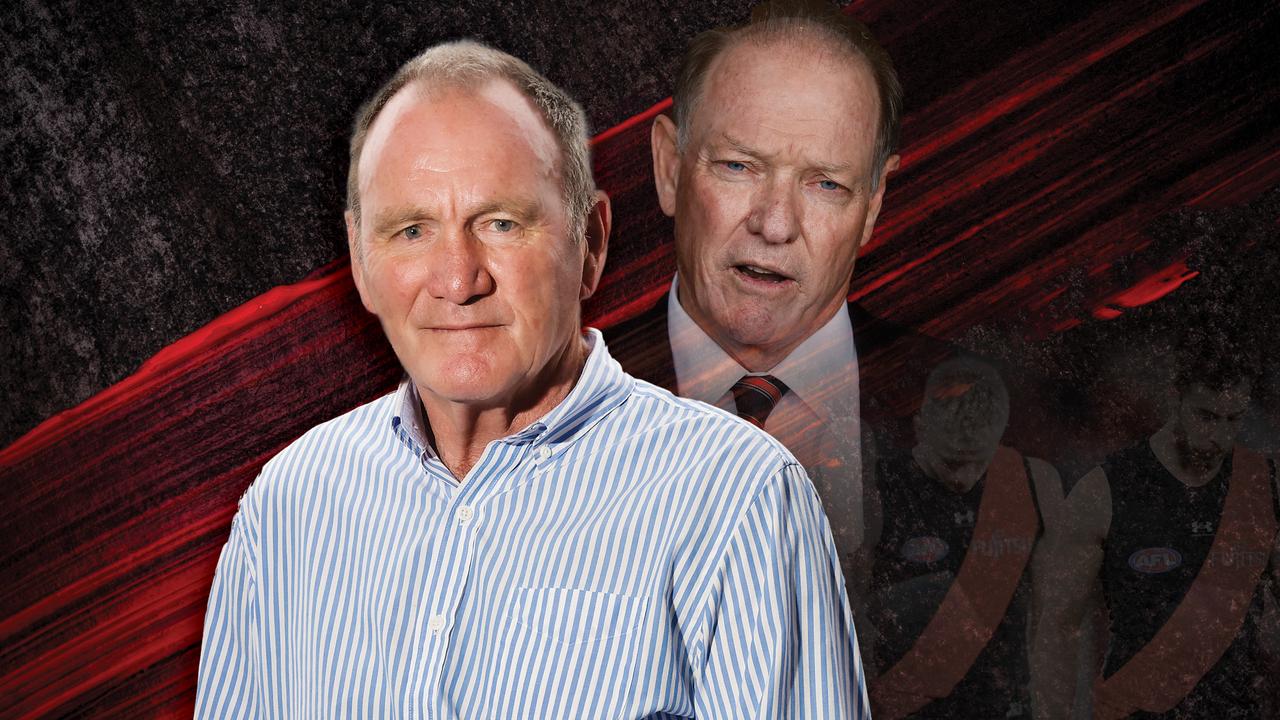

Sam Newman’s portfolio of poison — my opinion — is prominent, so is McGuire’s seemingly constant showings of support, humour and contradiction.

When the 13-year-old girl called Goodes an ape, McGuire apologised on behalf of football and on behalf of Collingwood.

“We’re well in control of this, we will do what needs to be done,’’ he said at the MCG.

Four day later, he suggested Goodes come to Melbourne to promote King Kong the musical.

Distressed, McGuire later broke down on radio.

“It is really hard ... if I’m feeling this this morning, I could only imagine what Adam Goodes has felt all his life.’’

McGuire’s heart is in the right place, his mouth not always.

After being named Australian of the Year, Goodes spoke of what it meant to be aboriginal and later campaigned for constitutional recognition.

Cue the angst.

Bolt: “All this monkeying around about, you know, who was recognised first and I want social rights, that is just so much palaver.’’

The booing was beginning to generate.

By the 2014 Grand Final against Hawthorn, it was sustained and venomous.

In Round 8, the following year, there was another Hawks game and more venom.

In some ways, the documentary is a suspense thriller.

It builds with anticipation and dread, as the booing coerces the mob, and then it explodes after Goodes’ war dance against Carlton during the Indigenous Round of 2015.

McGuire: “Had we known before the game Adam Goodes and the indigenous players were planning to do a war cry, we could’ve been able to educate and understand the situation.’’

Commentator Charlie Pickering fired back at McGuire.

“Eddie’s right, there should’ve been more education. Sure, it was the AFL’s indigenous round and it was an indigenous player with an indigenous mouthguard wearing an indigenous guernsey, scored with an indigenous ball, but you really need to warn people when s--t’s about to get all indigenous.’’

The incident inflamed Australia.

White men and white women passed judgment, black men and black women offered context.

Commentator and former footballer Gilbert McAdam said: “What a great topic we’re discussing on the Marngrook Footy Show, where all the people are just about aboriginal, grew up as aboriginal, we know what we’re talking about. Mainstream media, 99 per cent of those people are non-aboriginal people. How are they experts? We’re experts because we’ve lived it.’’

Commentator Waleed Aly said: “There’s been people talking all week about, ‘why are people booing Adam Goodes’ as though there was some mystery about it. No, there’s no mystery. It’s about the fact that Australia is generally a very tolerant society, until its minorities demonstrate that they don’t know their place.

“And at that moment, the minute someone in a minority position acts as though they’re not a mere supplicant, then we lose our minds. And we say, ‘no, no you’ve got to get back in your box here’. The backlash is huge and it is them who are creating division and destroying our culture and that is ultimately what we boo. We boo our discomfort.”

Commentator Stan Grant said: “We don’t hear just the boo, we hear the howls of humiliation that we often grew up with as indigenous people. That ‘howls of humiliation’ which echoes across two centuries of dispossession and injustice and suffering ... and the mark it leaves on your body and the mark it leaves on your soul.’’

Here’s a breathtaking exchange between Bolt and ABC Radio’s Charlie King from Darwin.

King: “Put yourself in Adam Goodes’ position and you’re the one white person in a whole aboriginal side, that has all aboriginal spectators sitting in the crowd mostly, all the commentators are aboriginal people, all the newspaper writers are aboriginal people and you’re the one white person in the side and you’re trying to do the best thing for your people and you celebrate with a little dance, and then they turn on you and start calling you names like monkey and ape and comparing you to King Kong ... how would you feel, Andrew?

Bolt: “I cop abuse ... you’ve got to get over some of this stuff.’’

All the while, Goodes was being booed relentlessly.

At one stage in the documentary, the screen goes black and only the booing can be heard.

It’s as powerful a moment as any.

The AFL, meanwhile, was confused. They wanted it to go away.

CEO Gillon McLachlan has since said he’d like his time again.

Because the boos continued. Against the Kangaroos. Against the Tigers, the Hawks and the Eagles.

A number of AFL coaches showed leadership.

Adam Simpson said: “I heard some booing ... I was hoping we’d a bit better than that.’’

Damien Hardwick said: “It’s bullying at its best and racism at its worst.’’

Ross Lyon said: “If you continue to boo Adam Goodes, you’re a racist and a bigot.’’

O’Loughlin told the Herald Sun he was watching the West Coast game with son James, who was then eight.

“He said, ‘Dad, did uncle punch someone in the face? Why are they booing uncle?’

“I knew the answer but how do you articulate that to someone who is seven or eight years of age? It was the toughest conversation I’ve ever had.’’

Goodes didn’t play the next round and disappeared to “put this feet back in the earth, feel country again, feel connected again’’.

O’Loughlin and Goodes are best mates and are different in character.

O’Loughlin is the black warrior and Goodes the black prince.

One is defiant and wants to put his flag in the ground and the other is calm, gentle, a “beautiful person’’.

O’Loughlin last week spoke to a group at St Kevin’s old boys.

“It was about culture and reconciliation and about Adam,” he said.

“Imagine being someone’s mother or father and you’re going to watch netball, football it doesn’t matter, and 50,000 people are booing your son or daughter?

“You’ve got your ticket, you grab your meat pie and bottle of water and you sit down, and every time your son or daughter touches the ball, they are booed relentlessly?

“I’d be in tears. The documentary shows a lot of that.’’

O’Loughlin has no more tears for his mate. He only has strength and pride.

“We need to get this kid back to the footy, to where he belongs,’’ he said.

“That’s my job, mate, and this documentary will help.’’