Last Monday, at just 58, Barry Mitchell was lying in Epworth Hospital wondering if the game he loves had almost killed him again. This is his confronting story the footy world needs to hear.

Last Monday, about 9pm, former footballer Barry Mitchell was lying in Epworth Hospital wondering if the game he loves had almost killed him again.

He wondered that 10 years ago, when a cancer tumour the size of a grapefruit was found and removed from his brain in a nine-hour operation.

This time, at a weekend away for a charity golf game in Shepparton, a seizure in front of 100 golfers had him carted off to hospital.

“My seizure apparently was shocking, it went for two minutes,” he said.

That was Saturday morning.

On Monday, he was transferred to the Epworth where he had an MRI scan, an EEG scan, gave blood, and was seen by neurologist Dr Robert Hurford.

On Wednesday, he had a lumbar puncture procedure.

“I had the brain tumour removed 10 years ago and they said it could be genetic coding because I have a history of cancer in the family,” Mitchell said. “But speaking to the neurologist this week, I said our era of protecting the head wasn’t there back when we played.

“Not that we were headhunted – and when I played the game was pretty good – but we were still being knocked around and bumped.

“I don’t understand it all, and I don’t profess to be an expert, but our brain function is probably diminished a bit due to the head trauma we suffered.

“We were trained and conditioned to be tough – to put your head in the hole – which was no problem, but it looks like the accumulation of knocks affects us later on, that’s how it looks.”

Instead of being in hospital, on Monday night Mitchell was supposed to be at a meeting of the FifthQtr Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation which supports AFL and AFLW player health and wellbeing beyond the game.

If he was at the meeting, attended by 50 former players at Ikon Park, Mitchell would have heard some of his peers, some of them champions of the game, tell how their lives had deteriorated to the point where they considered suicide.

One former player in attendance described the storytelling as “horrifying”.

The broader plea is that they be heard and treated in a compassionate and caring manner, not just by the AFL, and the AFL Players’ Association, but also by the clubs they represented with every ounce of body and soul.

Of course, they’re all for looking after the players of the now, but they fear for the players of the past.

Mitchell wants immediate action. He’d prefer not to grandstand with his issues, but is frustrated by the lack of empathy and support the former cohort receives from the league and the AFLPA.

“I don’t want to be the figurehead, but I don’t mind if I am because I’m not hiding from it, and I’m not putting my hand out for money,” he said.

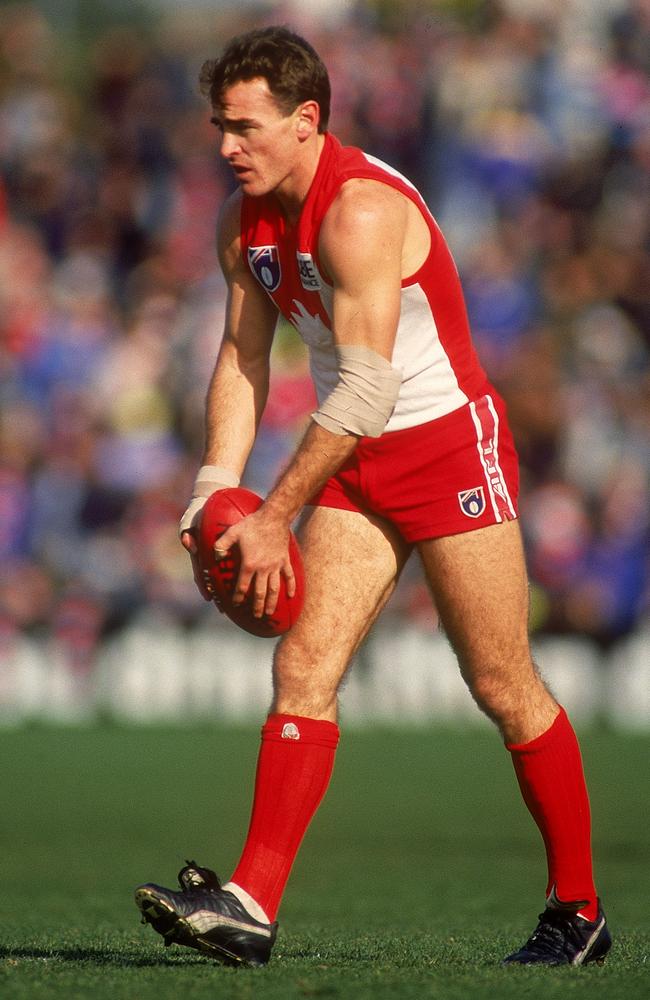

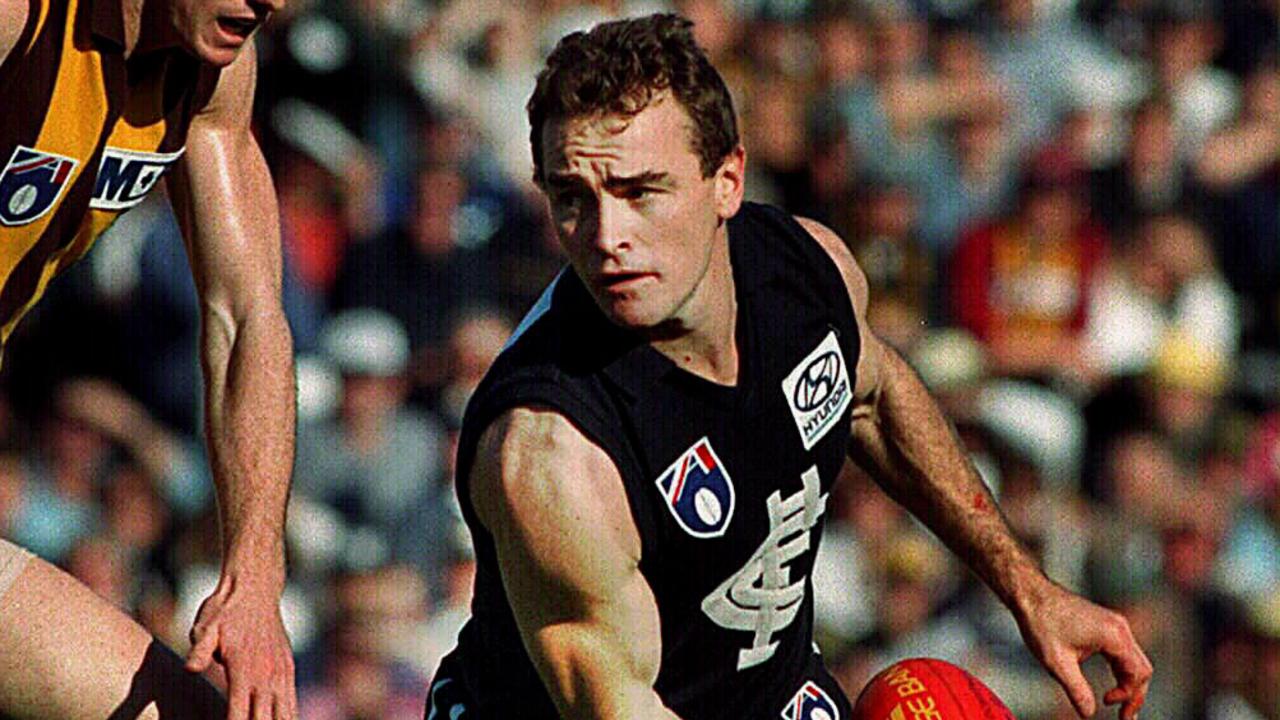

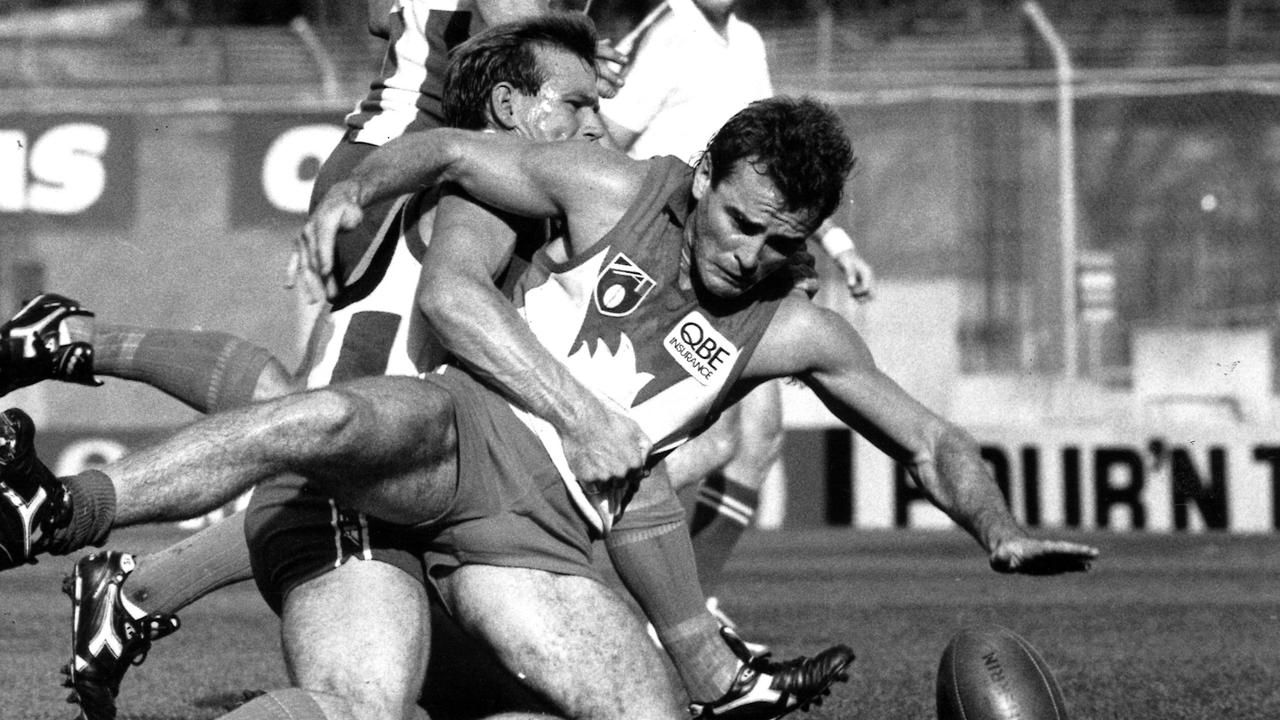

Just 58 years old, Mitchell played 221 games for Sydney, Collingwood and Carlton from 1984-96, and was known for his tenacious, hard-running and ball-winning capability.

In 1992, for example, he averaged almost 30 disposals per game in an era when 320 team disposals was the norm. His single-game career-high was 43 touches.

For the younger crowd, he’s probably best known as the father of Brownlow medallist Tom Mitchell, also a prolific ball-winner.

Football was his everything. After retiring, he was a runner and then assistant coach at the Blues under Denis Pagan – which was a challenging relationship – an assistant at Hawthorn under Alastair Clarkson for one year (2008) and was the same at Fremantle under Mark Harvey. His last full-time job in football was as a Swans recruiter, although he can’t remember the exact years.

That’s one of his problems – memory loss – among a slew of issues he believes playing football has given him, starting with the tumour, which was detected after months of lethargy and irritability.

Frankly, he doesn’t know if his brain injury was caused by the tumour, or if football brought on the cancer.

“The specialists don’t know,” Mitchell said.

I played a lot of footy; I took my bit. I played how you were supposed to play, but I didn’t think I would finish up here, not at 58.”

As well as memory loss, noise disturbs him. He wears headphones in crowds. Loud cars, dogs barking and kids playing unnerves him.

“Any form of pressure I don’t enjoy,” he said.

“I’m more direct and less tolerant. I get disoriented very easily. I get lost a lot – lose my keys. Lose the dog. I can lose anything. (But) I can function – I’m reasonably intelligent – but I can’t multi-task. If my emotions are heightened, they are more difficult to control. I know I lack filters at times … it’s just difficult to live in the modern world with a brain injury.’’

Mitchell knows he’s not alone.

“I have mates, contemporaries, who have got CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) symptoms,” he said. “I can’t speak for them and their conduct, but I think there’s a hidden pandemic and people don’t want to admit they’ve got symptoms. If people admit it, then their professional life can be questioned as to whether they’re up for their job.”

An admirer of long-time friend Neale Daniher, Mitchell wants the footy world to rally around suffering past players like it has with Daniher. A past players’ round, promoted like Sir Doug Nicholls’ Indigenous Round, or Pride Round, or Gather Round, is one idea.

“Before Neale Daniher, I defy anyone to know what MND (motor neurone disease) was and it’s been a great cause,’’ Michell said. “I see CTE as a by-product of our game, and it’s a great game and no one who played would take anything back, but I don’t think the sport is set up for us when we become incapacitated.

“At the moment, it’s like we have to sue the AFL to get a result and I don’t think that’s right.

“I’d like an independent concussion board or group – with AFL people on it, doctors, concussion experts, people who have CTE symptoms and parents.

“I think the AFL would look good for everybody’s sake if they say, ‘Hey, we recognise this’, just as the NFL in America has done.

Because among the former players, we’ve got broken relationships – I got divorced – there’s gambling, drug-taking, drinking, which is self-medicating … we’ve got champion players who are zombies.’’

As an example, Mitchell said he estimated 16 of the regular 24 players who played for Sydney in 1986 had issues ranging from neurological (disorders) to cancer to drug and alcohol-abuse. “And that’s just one group of guys,’’ he said.

“It shouldn’t be litigation that decides this. None of us want to do it, but to make it in football, you’ve got to have shit in you; be prepared to stand up for yourself, and when we become vulnerable, we’ve got blokes who want to decide it aggressively or physically because that’s what we’re used to doing.

“But we’ve got to be smart, we’ve got to be co-ordinated, we’ve got to be honest. Everyone’s got be honest.”

He stressed he wasn’t angry about his predicament – “I’d say frustrated,” he said – because “I look back and think people didn’t fully understand the collision nature of the sport”.

“We gave some players a badge of honour about how they played,” Mitchell said. “OK, but what happens to them later in life? This was the part none of us understood, and trust me, there’s more coming.

“Look at all the current players who have been knocked out half a dozen times. And it’s not just been concussions, it’s the body-knocks, it’s the movement of the brain when you get hit.

“The concussions are easy to see. It’s the tackling, the amount of times you go to ground when you’re tackled, it’s when you get a clip, it’s the stuff you can’t add up.”

Mitchell accepts that some former players want and need financial assistance, and he feels for players at all levels who are “on their own, isolated, lost their families, lost their jobs”.

“It’s a call-to-arms, it’s about coming together as a game, and being proud to look after our people,” he said.

“Like, you’re happy to cheer for Joel Selwood, or whoever that guy is, but when he’s buggered, just don’t forget him. That’s everyone, not just the heroes.”

Asked if he attempted to mask issues in front of, say, his son Tom, Mitchell said no, before adding: “But Danny Frawley was performing well on camera, too.”

He acknowledged there’s a public-relations battle to convince people that cries for help were not simply money-grabs.

“Brain trauma is real,” he said.

“I don’t think any one of us understood going into this game what it would do. And we judge all these peoples’ behaviours, and they are good fodder for the newspaper, but I don’t think there’s a great understanding or tolerance for people who, quite possibly, could be injured.

“As Mark Maclure said in your paper, you don’t know until you’ve got it. And we’ve got to look after (the) people around that person – partners, kids. Who’s helping those people?”

If he had a private audience with AFL chief executive Andrew Dillon, Mitchell would tell him: “This is a problem that can be kicked down the road, or we can do something about it now. So, let’s start meaningful conversations and accept our responsibilities now. And whatever comes of it, will come with us doing it together and not in opposition.”

Pointedly, his plea is for help with financial assistance, rehabilitation, specialist care, medication – and even someone to talk to when the world closes in.

“I don’t want to look desperate, or look like I’m complaining – I’m not complaining – I’m not a victim, I have no regrets about playing, but I do want to be someone who does something about it,” he said.

“(Past) players are a pretty resilient group, and we’re mostly internally strong, but when that goes and your filter breaks, and your relationships break down and your life starts to break down, who is going to help us?

“You can say the AFLPA does (help past players), I don’t know. I called them a week before I had the seizure and I got a text back which said they will call me in a week.

“It’s a sad world, when we have to come to you (the media) to try convince people we have a problem.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

‘Financial juggernaut’: Tassie legends laud Macquarie Point Stadium vote

Two of Tasmania’s finest football products believe the decision to pass the Macquarie Point Stadium development will have a massive impact on future generations.

Revealed: The Top 30 SANFL recruits for 2026

Plenty of big names, including a Magarey Medallist and top-10 AFL draft pick, have flooded to the SANFL. Here’s the league’s top 30 pre-Christmas recruits.