Cyril Rioli’s retirement feels like a death in football, writes Mark Robinson

IT’S silly, but it felt like a death in football. Cyril Rioli was the Velociraptor of the field. The smart one, the predator with speed and brains — he could turn, shuffle, step and dance, all the while staying balanced, writes Mark Robinson.

Mark Robinson

Don't miss out on the headlines from Mark Robinson. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT’S silly, but today felt like a death in football.

Not a retirement, as Cyril Rioli announced, but something much more affecting, much more mournful.

It’s only football, but when there’s a sense of loss, in this case the loss of joy and wonderment, the sadness is real.

RIOLI RETIRES: OPPONENTS PAY RESPECT

BEST EVER?: CYRIL THE MAN FOR THE MOMENT

CASHED-UP HAWKS PREPARE TO LAUNCH

The measure of the type of player Cyril was — and who could ever appropriately describe his magnificence? — is explained by the outpouring of so many memories by so many people today.

And by sporting definition, any player known simply by his first name carries such a level of respect, identity and achievement that not much else really has to be said.

It didn’t stop the avalanche of accolades, of course, for Cyril was a gift to the game.

If the football field was Jurassic Park, Cyril Rioli was the Velociraptor.

He was the smart one, the predator with speed and brains — he could turn and shuffle and step and dance, all the while staying balanced and focused and hungry.

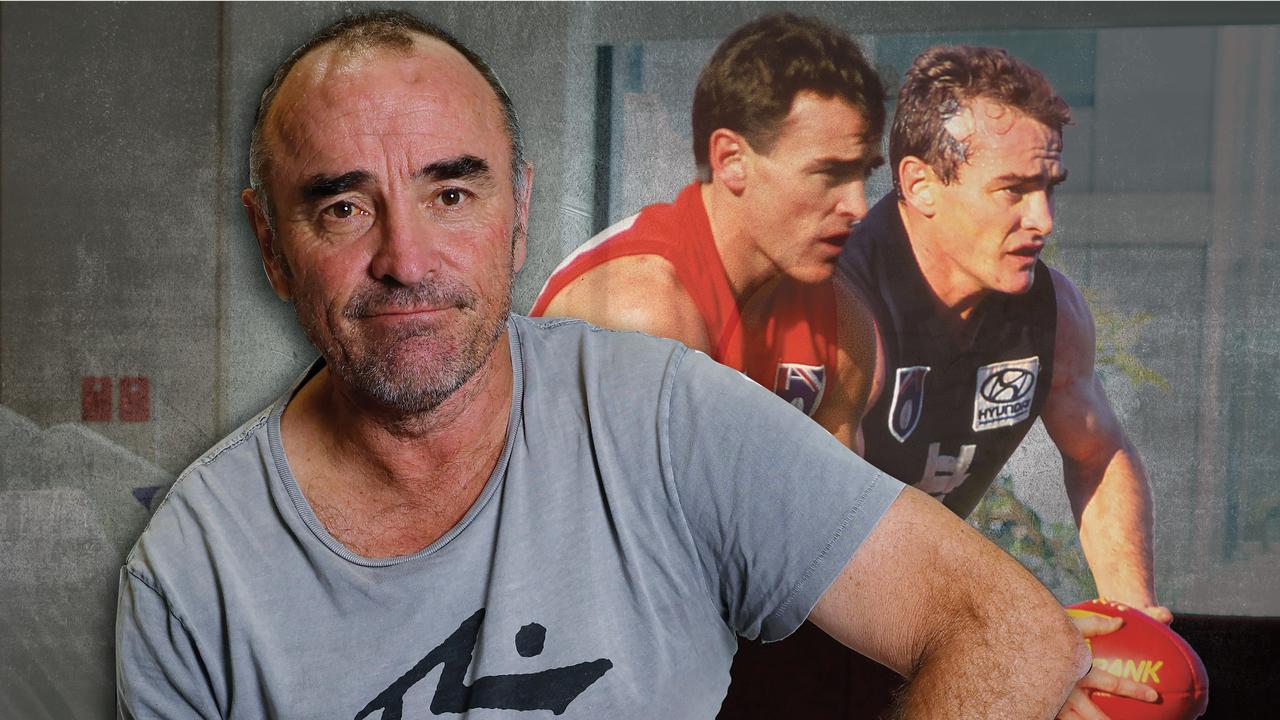

Bob Murphy once said being chased by Cyril was like having a great white shark in pursuit of him.

Not only was he gripped by the anxiety about the lack of time and space, but also by fear.

With the ball, Cyril was virtually impossible to tackle.

Hope this makes sense, but he seemed to know where the tackler was coming from and where he was trying to go, and simply got out of the way.

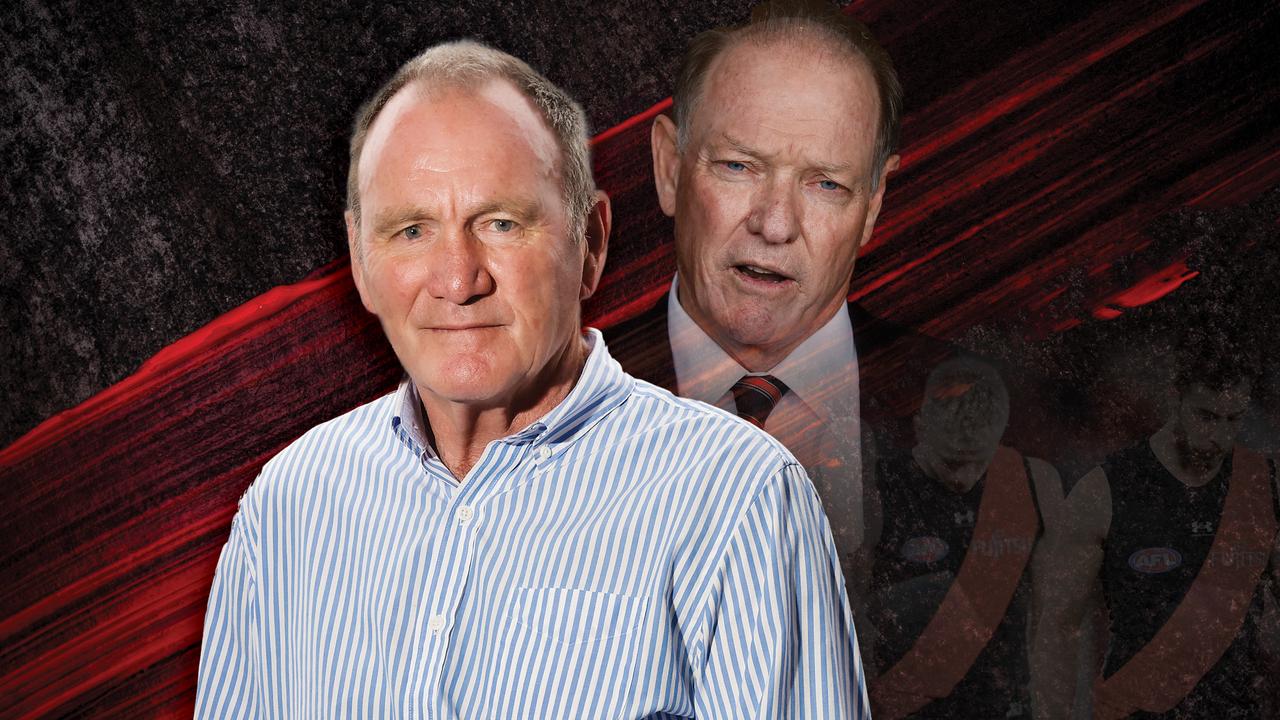

Dermott Brereton has said in the sports pages today you’d “never see Cyril get tackled because his awareness was so good … he was so good, even if Cyril couldn’t see them, he could hear them breathing”.

There was an enchantment about Cyril.

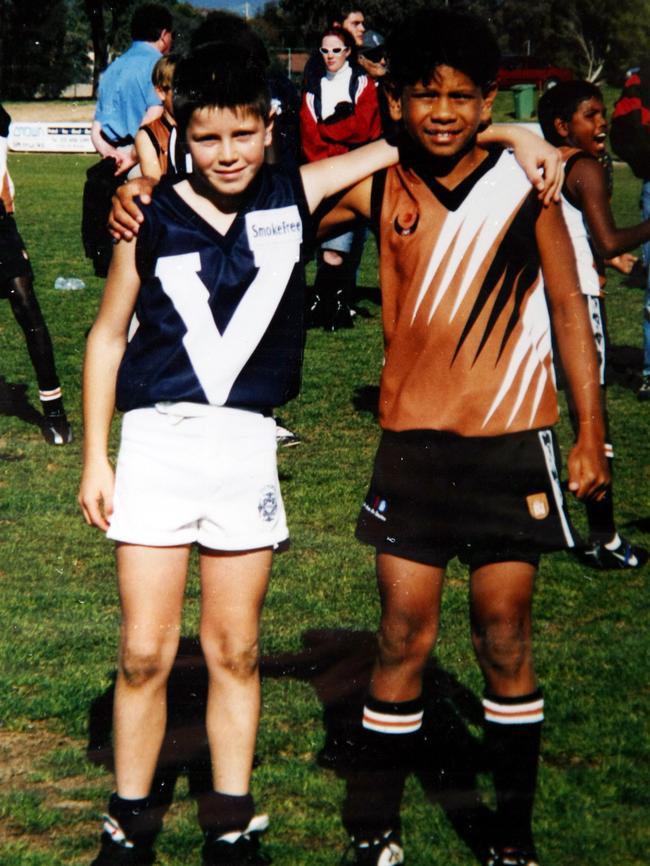

It was there when we first learned there was yet another young teenage Rioli dazzling with a beaten-up Sherrin amid the muddy fields and palm trees on the Tiwi Islands.

He was 13 or 14 then, and when he was eventually drafted in 2007, what arrived was a shy boy with speed and a strong family connection and reputation.

Before Cyril arrived in the AFL, there was uncle Maurice, cousin Dean and uncle Michael Long.

It was Long who said it would be wise to monitor young Cyril.

He didn’t say much else, but it was enough to know a bolt of lightning would soon arrive from the north.

BUCKENARA: EVERY CLUB’S SEASON ANALYSED

Cyril was taken at pick No.12 in the national draft.

Only two players before him — Trent Cotchin (No.2) and Patrick Dangerfield (No.10) — are in the same sphere of accomplishment from that year.

Cyril is different to Cotchin and Dangerfield.

They are brilliant in their own way, but not as brilliant as Cyril.

Imagine if Cyril could accumulate like Cotchin or Dangerfield, delivering multiple

30-plus disposal games across his career?

If he did, he would be hands down the greatest player to have played the game.

It was always a knock on Rioli that he didn’t get enough of the ball.

I’d prefer to think of it as Rioli’s maker didn’t want to make it totally unfair on all the other players, so instead of the total package he gave him magic, not stamina; speed, not height; and humility, not arrogance.

That package was mesmerising.

But he’s gone, and we really didn’t know him as a person.

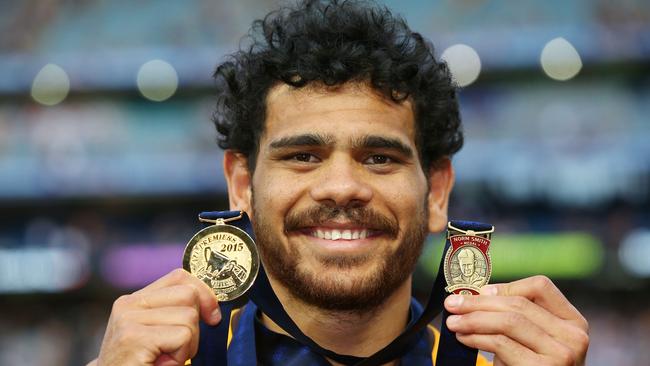

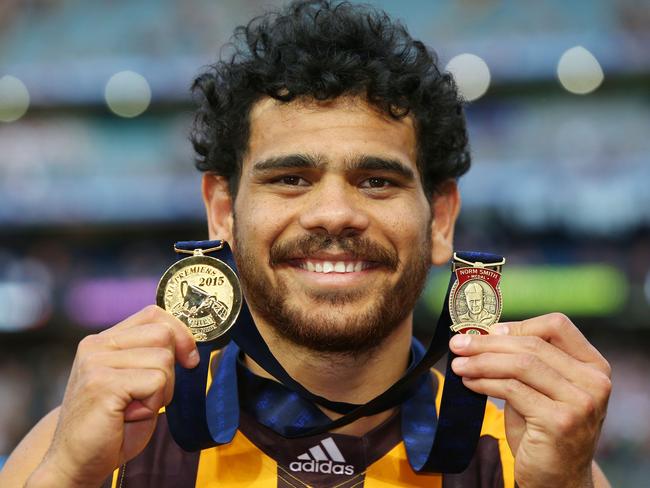

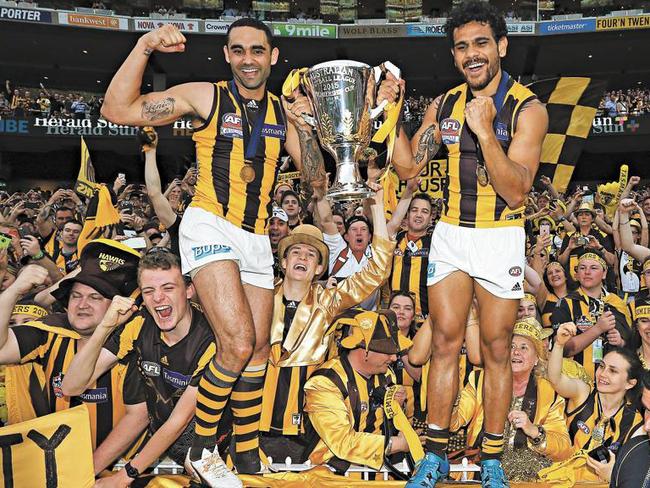

After 11 years, 189 games, four premierships and a Norm Smith Medal, we sort of knew Cyril the footballer without ever really understanding Cyril the footballer.

Why is it he could find gaps in packs when others found a dead end?

Why was he able to consistently take the ball on the burst out of the pack?

How could he tap it between legs and around knees and gather it on the fly without an opponent laying a finger on him?

Why could he hang in the air for that treacherous extra second when taking a mark, seemingly balancing on air and not an opponent?

It tends to get called innate.

Or it’s because of his genes.

Or his instinct.

Whatever it is, Rioli had it.

He leaves the game for family reasons.

At 28, and with two years to run on his contract, he might have given up as much as $1 million.

We learned a hell of lot today about Cyril the person, mainly that his family needs him more than he needs football.

The Hawks would be both disappointed and blessed.

Disappointed Rioli won’t be part of the planned renaissance and blessed that he was there in the first place.

“Cyril came into our club as an 18-year-old kid and leaves an integral part of the fabric of the brown and gold family and the history of our game,’’ coach Alastair Clarkson said.

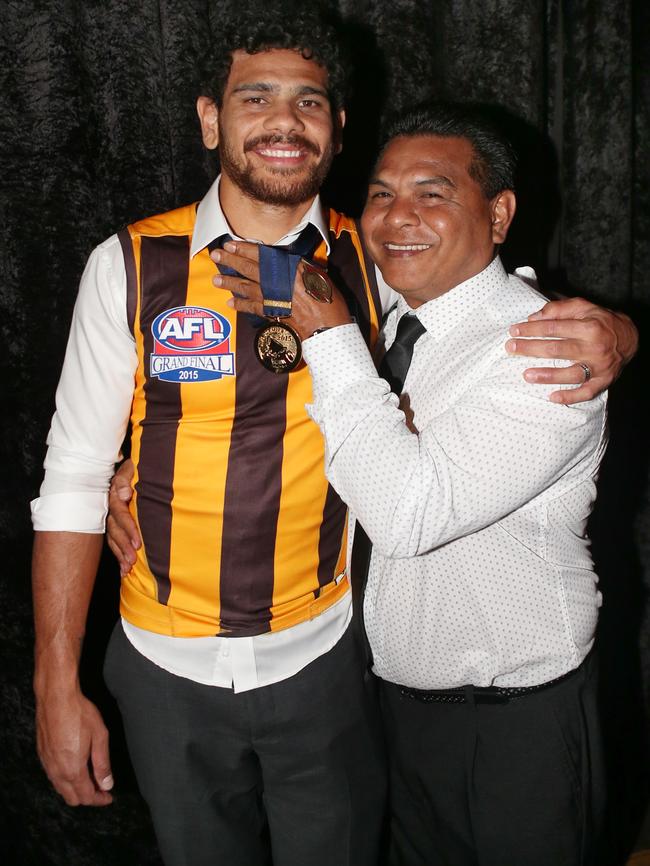

We already knew family was important for Cyril, for his body is layered with tattoos.

The one on his chest is of a wing-spread hawk with the words: Live the life you love. Love the life you live.

On his back is the family name — RIOLI — from shoulder to shoulder.

And just above his pectoral muscle on his chest, on the right, one says DAD.

It’s rare to recognise your dad so prominently while he’s still alive, but if you’ve ever watched Peter Dickson’s soul-stirring video of Cyril and his dad for the AFL season launch in 2016, you might begin to understand their incredible connection.

The video was called Stay the Path.

Now it’s all over, the football world salutes Cyril

for shining the light not only on the pathway he took, but also what his pathway delivered.

Make no mistake, the only thing that died today was a football career.

But, gee whiz, for a while there it felt worse than that.