World War II vets kicked off outlaw bikie culture

A violent brawl between biker gangs in the US has resulted in nine deaths, an echo of Australia’s Milperra Massacre. But our bikies originally drew inspiration from America’s outlaw motorcycle groups

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The death of nine people in a fight between rival motorcycle gangs in the US will remind many Australians of the 1984 Milperra Massacre, when six bikies and an innocent girl died.

The concept of the outlaw motorcycle gang came into existence in America in the late 1930s and 40s.

Motorcycles in one form or another have been around since the 1880s, initially as motor-powered bicycles.

Eventually manufacturers created machines built from the ground up, testing them in races that began to inspire groups dedicated to the two-wheeled vehicles.

Some of the earliest motorcycle clubs were either offshoots of cycling clubs or were cycling clubs that became motorcycle clubs.

The Yonkers Motorcycle club, formed in 1903, thought to be the oldest motorcycle club in America, was originally a cycling organisation. Such groups mostly gathered together to take rides in the country and to attend motorcycle race meetings.

In 1927 motorcycling enthusiasts formed the American Motorcycle Association (AMA).

Members were largely law abiding, machine loving enthusiasts who enjoyed riding, but in the ’30s other motorcycle groups formed with less wholesome attitudes, operating outside the AMA.

One of the oldest clubs of this kind is the McCook Outlaws, formed in 1935 in McCook, Illinois.

They would later become known simply as the Outlaws, spreading across America and eventually around the world.

After WWII returned soldiers who like bikes, used to the hard drinking, action-packed life they had experienced during the war, also formed motorcycle clubs across the country.

The most famous of these, formed in 1948, was the Hell’s Angels — the name inspired either by the 1930 Howard Hughes film based on the exploits of WWI pilots or by the nickname of a US air force squadron from WWII.

It became a subculture that focused on long rides, often over tough terrain or winding roads, bike races, boozing, womanising and communal living.

That subculture became more widely known when, in 1947 in Hollister, California, drink-fuelled bikers who had attended an official AMA Gypsy Tour bike race, began holding their own informal races through the middle of the town.

The police moved in to clear the bikers out of the town, resulting in 47 arrests.

Three bikers were injured in the melee, one with a fractured skull, but the incident was exaggerated in news reports that depicted it as a major riot, blaming lawless bikers.

The AMA was allegedly reported as distancing itself from the “one per cent” of bike riders who broke the law.

Some of the fringe group bikers adopted the expression “one-percenters” as a badge of pride, a sign of their disregard for authority.

They became known as outlaw motorcycle clubs.

The Hollister incident inspired a short story — The Cyclists’ Raid — in 1951 that became the basis for the 1954 film The Wild One, starring Marlon Brando.

Many outlaw clubs based their sense of style on the film, even basing their logos on the one used by the fictional Black Rebels in the film, using a skull and crossbones.

The film would also inspire many other motorcycle gang exploitation films and establish the image of the biker as a rakish, unpredictable law unto himself.

The film did much to romanticise the subculture but over the next few decades the biker lifestyle, often already seen as misogynistic, violent, alcoholic and at times even racist (some gangs even adopting Nazi symbols), took on an even more sinister tinge as some became involved in criminal activities.

The bikers found it hard to avoid bad publicity.

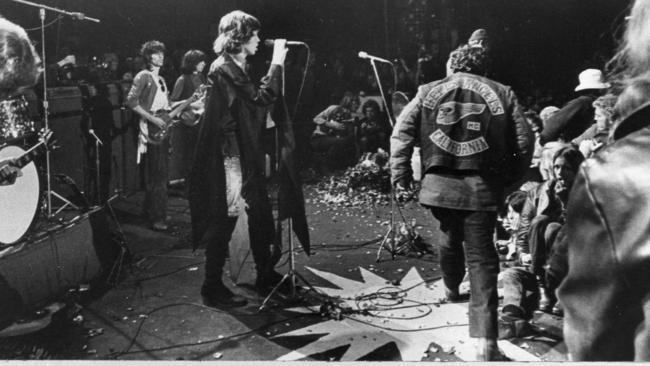

Like the incident when Hells Angels bikers took it upon themselves to act as security at the Rolling Stones concert in Altamont in 1969, where one of the bikers stabbed to death a man running at the stage with a gun.

In recent decades the image of the outlaw motorcycle gang has continued to be tarnished by stories of their involvement in organised crime and with violence between gangs spilling out into the civilian world.

Originally published as World War II vets kicked off outlaw bikie culture