‘My brother was commanded to shoot your son’: Why the Aussies killed in the Great Escape live on

An Australian murdered in the infamous wartime Great Escape died after swapping places with another man. And his story is still unfolding, 80 years on.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

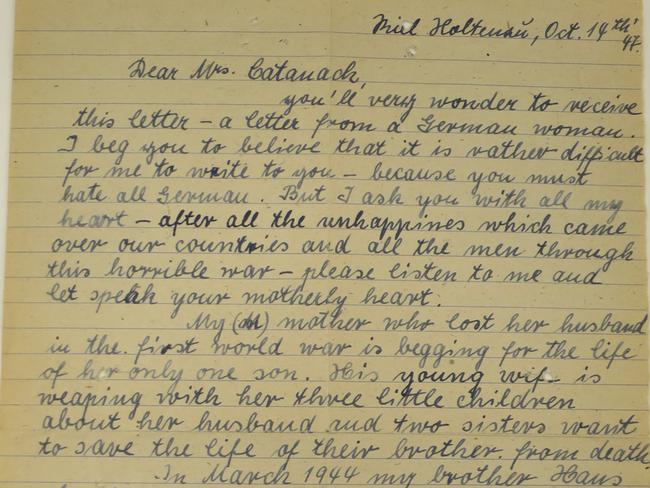

“My brother was commanded to shoot your son”.

In the years after World War Two, a letter arrived for the grieving mother of James Catanach, who had been one of Australia’s most young promising airmen before he was shot down, imprisoned and ultimately murdered by the Nazis.

The letter was from the sister of one of the Gestapo men – Hitler’s feared secret police – who had executed James and 49 other prisoners of war, in the aftermath of the legendary breakout known as the Great Escape, 80 years ago this weekend.

Four of those men were from New South Wales: Squadron Leader John Williams, a Manly surfer who became a decorated fighter pilot; his mate and fellow fighter man Flight Lieutenant Reg “Rusty” Kierath, of Narromine; Sydney Spitfire pilot Warrant Officer Albert Hake, who had been married just a few months before he was sent overseas to action; and Waverley-born Flight Lieutenant Tom Leigh, the rear gunner in a Halifax bomber.

The letter-writer, Elly Koester, was begging forgiveness for her brother Hans Kaehler, in the hope it might help him avoid the noose after he was found guilty at a war-crimes trial for his role in the horror. She claimed he had been ordered to take part and had tried to avoid being involved.

“My grandparents did not respond to that letter,” says Amanda Catanach, James’ great-niece. The family, owners of the famous Melbourne jewellery company Catanach’s, were just too distraught – and understandably so.

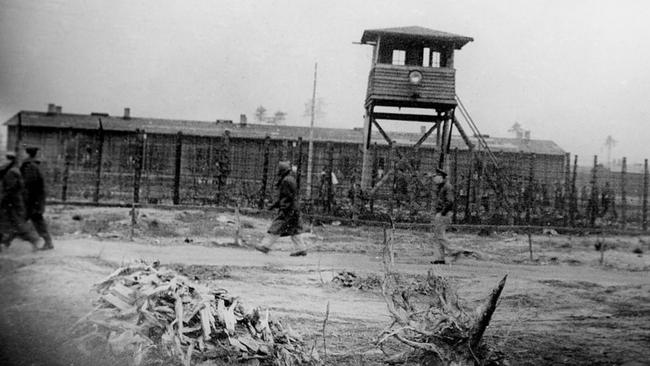

For the murders were part of a ghastly and elaborate fabrication carried out on the personal orders of Adolf Hitler and senior Nazis, furious that such a daring mass escape had happened under their guards’ noses at the Stalag Luft III camp for captured airmen.

The breakout – immortalised, in fictionalised form, by Hollywood classic The Great Escape – involved months of work digging secret tunnels, preparing escape kits and plotting routes, before 76 men crawled under the wire on the night of 24/25 March, 1944.

Nearly all were recaptured – just three made it to freedom.

Then Hitler demanded his murderous retribution, first insisting they all be slain before deciding 50 must die.

“It’s just terrible, the collusion that went on to effect those orders,” says historian Kristen Alexander, author of Kriegies: The Australian Airmen of Stalag Luft III.

First, she explains, “the men were ordered to be shot, as an example,” to other potential escapees. The bodies were cremated, rather than returned to the compound near Sagan for honourable burial as was customary – although their ashes were sent back, “also as an example”.

Meanwhile Gestapo men agreed to lie that the prisoners were shot in the act of fleeing, rather than later in cold blood.

“They clasped hands and took their oaths that they would stick to this story,” says Dr Alexander, of Kaehler and the group that killed James. “And this same conversation is being carried out (by Gestapo groups) across Germany.”

In some cases, she adds, death certificates were faked to indicate the men died of “natural causes”.

The truth was very different. By the time they were recaptured, the prisoners were already scattered across Germany in small teams. Most were first taken to local holding facilities and questioned. Many were later taken into Gestapo custody where they were again interrogated, photographed and taken to secluded places of execution.

Dr Alexander says the airmen saw it as their duty to attempt escape, not least because the manhunt would cause problems for a Germany already on the back foot in the war; and believes is important that today we “honour their beliefs that the enterprise was worthwhile”.

However few would have anticipated the horrific penalty. Being shot while running was a real risk, but once caught most would have “assumed they’d sent back to, if not Stalag III, some other prisoner of war camp” for a spell in solitary, she says, based on what had happened to previous escapees.

Dr Alexander tells how WA pilot Paul Royle, who was caught but survived, was in a group that was split up, with some men taken away by their captors. “One of them was an Australian and he had very, very bad frostbite so could barely walk,” she says. “They assumed he was being taken to hospital.”

That was Sydney’s recently-married Albert Hake. Despite his condition, he was driven to a wood with Tom Leigh and four others, told that “the sentence was about to be carried out” and gunned down in two salvos.

In the case of 22-year-old James Catanach – a high-achieving Geelong Grammar student who had become the RAAF’s youngest squadron leader, awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his exploits flying Hampden bombers – there is a chance he may never have realised what was happening.

Along with three others he was caught at Flensburg while trying to reach Denmark by train.

They were piled into Gestapo cars where, according to trial testimony from Kaehler, James was making amiable conversation with his captors when the convoy halted in open country, ostensibly for everyone to stretch their legs before resuming the journey to Kiel Gestapo base.

It was then that he was shot, from behind.

“From the testimony, it doesn’t seem as if Jimmy had any idea until the last moment and he may not even have had any idea at all, because he was shot in the back,” Dr Alexander says, adding a caveat that the Gestapo accounts should be taken “with a grain of salt”.

The testimony did Kaehler no good, nor did his sister’s letter – nor the defence plea that following Hitler’s orders was legal and there was no choice but to obey. Kaehler was hung, along with 13 others, in early 1948.

The scars of the incident lingered long after, for relatives of the fallen, for the escapees who were recaptured but lived – many suffered “survivor’s guilt” because they were spared while others were chosen to die – and for the thousands more who suffered the trauma of being a prisoner of war.

There were 351 Australians held at Stalag Luft III, still more at other camps, among many thousands of Allied prisoners.

But for later generations, like the Catanach family, the shared inherited experience is not all one of bleakness.

Ahead of going to the Australian War Memorial on Monday, where James will be the focus of commemoration at the daily Last Post ceremony, Amanda told how the family continue to piece together elements of his story through contact with descendants of fellow prisoners from all over the world.

“It’s a constant story,” she says. “Through my lifetime, we’ve met some incredible people connected to Jimmy.

“For example, I got an email from a guy in Norway, saying that he had James’s watch.”

That man was the son of a Stalag prisoner to whom James had given the watch before fleeing, because it was engraved with the name “Catanach” and would have been a giveaway.

The families met, the watch was returned and was presented by the family, along with other memorabilia, to exhibit at Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance.

Another revelation came when the family learned a Canadian airman who was initially supposed to be in the tunnel had agreed to swap with Jimmy, “who was terribly homesick and desperately wanted to get home to his fiancee here”.

The family of that fiancee, Heather Ebbott, have very recently given the Catanachs an album of treasured photos and letters, adding yet more to what Amanda calls “a story that keeps giving”.

Preparing for Monday’s Last Post, the Australian War Memorial Director Matt Anderson said: “James’ story is a reminder that ordinary Australians are capable of extraordinary deeds. There are 103,000 unique stories on our roll of honour and many times when I hear their story at our Last Post Ceremony I look at the family of the veteran. And most often, my mind turns to those who are not there. Those who never came into being because the soldier, sailor or aviator never made it home.

“Like many servicemen James died so young that he did not have children. The family coming on Monday are not his children and grandchildren but his nephews and nieces and their children. So what I imagine during these ceremonies are his direct descendants who are not there because they were never born. They are as lost to us as he was lost to Australia.”