Why we’ve always looked up to the elegant giraffe

With only 80,000 giraffes left in the wild, the Giraffe Conservation Foundation has designated June 21, the longest day of the year in the northern hemisphere, as World Giraffe Day.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

DESPITE its elegant beauty and gentle nature, tragedy befell the first giraffe transported to Europe by Roman emperor Julius Caesar, on his triumphant return from Egypt.

The giraffe, called a “camelopard” for its combination of camel and leopard characteristics, was the star of a menagerie Caesar imported in 46BC. The creature met a gruesome end, torn to shreds when Caesar threw it to lions at the Coliseum.

With only 80,000 giraffes left in the wild, the Giraffe Conservation Foundation has designated June 21, the longest day of the year in the northern hemisphere, as World Giraffe Day to raise awareness and funds to support conservation efforts in Africa.

Displayed in Alexandria since at least 300BC, descriptions of camelopards from 14th century European explorers enhanced their appeal to Italian nobles, including Duke of Naples Alphonso II and Hercules, Duke of Ferrara, who added a giraffe to their menageries.

Lorenzo the Magnificent, Florentine noble Lorenzo de Medici, in 1486 took delivery of a giraffe, a gift from Sultan of Baylonia al-Ashraf Qaitbay. The “dainty, graceful female” giraffe, fed sweet treats by Florentines, lived in a stable where it was tended by nuns.

Descended from antelope-like animals with slightly elongated necks found on African grasslands 15 million years ago, animals similar to modern giraffes evolved about 9 million years ago. The modern species, standing 4.5-5m tall with a 2m-long neck, evolved about 1 million years ago.

Their exceptionally powerful hearts pump blood at the highest pressure of any animal to reach its brain 2m above. African myths explain giraffe height was caused by herbs given by a magician during drought, although scientists explain long necks as a sexual selection adaptation.

Male giraffes fight for females by “necking”, where they stand side by side and swing the backs of their heads into each others’ ribs and legs. Giraffes also have thick skulls and ossicones, a hornlike growth, on top of their heads to use as battering rams to break their opponents’ bones.

Native to savannas, grasslands and open woodlands from Chad in the north to South Africa, and from Niger east to Somalia, they feed mainly on acacia leaves. Belonging to the family Giraffidae, which shares a common ancestor with deer, goats, sheep and cattle, its only relative is the solid brown and part-striped okapi, physically more like a zebra.

The scientific name giraffa camelopardalis acknowledges Roman descriptions of “a creature combining, though with infinitely more grace, some of the height and even the proportions of a camel, with the spotted skin of the pard”. Different coat patterns distinguish nine subspecies.

Ancient Arabic names include saraphah, gyrapha, gyraffa and zirafa/zarafa, translated as fast-walker. Persians called them ushturgao, or camel-cow. The Somali name was geri. Italians gave the name giraffa in the 1590s.

English animal dealer George Wombwell advertised a camelopard in his travelling menagerie in 1805, although it died within a few weeks. Sceptics suggest Wombwell’s giraffe was actually a white camel painted with yellow spots.

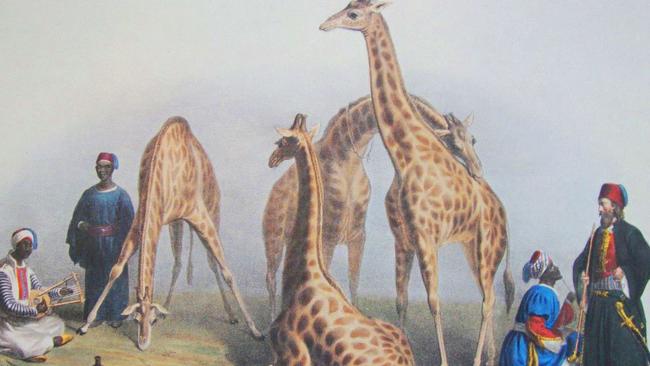

French consul general in Egypt and exotic animal trader Bernardino Drovetti in 1824 suggested Mohamed Ali, former Albanian mercenary and self-appointed Egyptian viceroy then planning war against the Greeks, send giraffes as gifts to win over European royals.

New French King Charles X’s gift was captured near Sennar late in 1825. Her mother was probably killed but the two-month old giraffe was persuaded to drink cows’ milk and strapped on to a camel. Carried 300km to Khartoum, she sailed 1700km up the Nile to Alexandria. Shipped to Marseilles by October 23, 1826, with Sudanese caretakers Hassan and Atir, she left for Paris on foot on May 20, 1827.

Walking 25km a day, the giraffe charmed crowds along the 800km journey, arriving late in 1827. After eating rose petals from the king’s hand, she was housed in the Jardin des Plantes public garden in the Latin Quarter. Named Zarafa, more than 60,000 Parisians visited her in July 1827. Women began styling their hair “a la giraffe”, trussing it so high they had to sit on the floor of carriages.

Zarafa lived until 1845.

Violinist Nicolo Paganini led a procession to Schonbrunn zoo in 1828, escorting Ali’s gift of a male Nubian Desert giraffe for Austrian emperor Franz II. It survived only about a year.

English King George IV’s gift, also captured near Senna, sailed from Malta in a ship with a hole cut into the deck for her head in May 1827 and arrived in London in August. First housed in a warehouse, she was sent by container to Windsor Great Park. Suffering injuries from her journey and perhaps poorly fed, she survived until autumn 1829.

Originally published as Why we’ve always looked up to the elegant giraffe