What became of Cliveden, Sir William Clarke’s Melbourne colonial mansion

It was home to Melbourne’s fanciest bachelor pads, with a private French chef and doctors, lawyers and High Court judges in residence. But Cliveden began as one wealthy family’s city home, the grandest seen in colonial Victoria.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was among the most opulent homes Melbourne has seen — a status symbol for Sir William Clarke, one of colonial Victoria’s greatest leaders.

Cliveden was a statement of ostentatious wealth but Sir William, a pastoralist, businessman and politician, was a man who also used his wealth for the betterment of Victoria.

Clarke, the Van Diemen’s Land-born son of a grazier and pastoralist with extensive rural property in other colonies, arrived in Victoria in the 1850s to manage his father’s agricultural interests here and buying farming properties of his own.

When his father died in 1874, Sir William inherited the whole empire and became one of Australia’s wealthiest men.

That same year, he began construction of Rupertswood, the mansion and sprawling country estate at Sunbury where the Ashes were created and presented as a joke to the losing English side in a friendly match with Australia during the team’s 1882/83 tour.

Clarke was a philanthropist who spent many tens of thousands of pounds supporting educational, scientific and artistic endeavours, along with a £10,000 donation to the construction of St Paul’s Anglican Cathedral.

His generosity was recognised by Queen Victoria, who created him a baronet, a rare hereditary title in Australia, for his generosity and his work as the president of commissioners for the Melbourne International Exhibition, the 1880 event at the Royal Exhibition Building that put Melbourne on the map around the world.

Sir William was also central to our sporting obsession.

He served as a president of the Melbourne Cricket Club, and was the inaugural president for the first five years of the Victorian Football Association from 1877, a commodore at the Royal Victorian Yacht Club and his filly Petrea won the VRC Oaks in 1879.

He served as a member of Victoria’s Legislative Council for almost 20 years.

While Rupertswood was his family’s home, named after his first-born son, Sir William also had a city residence in St Kilda.

But he aimed for something much grander at the height of Marvellous Melbourne in the 1880s, a time when the city was among the world’s wealthiest thanks to the gold rush.

That was Cliveden, a three-storey Italian Renaissance-style wonder in East Melbourne that became central to Melbourne society, National Trust of Victoria advocacy manager Felicity Watson said.

“It was a big statement for Sir William Clarke. The 1880s was a very affluent time in Melbourne and a time when lots of grand buildings were being constructed,” she said.

The home was designed by renowned architect William Wardell, who designed St Patrick’s Cathedral, and W.L. Vernon and it was extravagantly appointed.

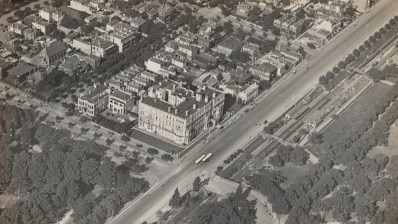

It was located at the corner of Wellington Parade and Clarendon Street in East Melbourne, opposite the MCG and the Fitzroy Gardens and a short walk from Parliament House and the central business district.

It had 100 rooms including 28 bedrooms, accommodation for a staff of 17, five bathrooms and a vast ballroom that was designed to cater for hundreds of guests. The home even had a tennis court.

Italian glass and oak panelling imported from England adorned the mansion, which was built by a team including craftsmen from overseas.

The East Melbourne of the 1880s was a model of Victorian-era splendour — but Cliveden was one of the largest private homes the colony had ever seen.

The entire Clarke family, including Sir William’s second wife Lady Janet and their brood of children lived in Cliveden.

Sir William endured the financial onslaught of the early 1890s depression, but as chairman of the Colonial Bank of Australia was left badly exposed. He succumbed to a sudden heart attack on May 15, 1897, aged 66.

He was survived by Lady Janet and nine of Sir William’s 12 children. Despite the strain and great personal cost of the depression, Sir William left behind an estate of more than £1 million.

Cliveden remained the heart of the family until Lady Janet’s death in 1909, when the property was sold to the Baillieu family.

But the Baillieus had no intention of making Cliveden a family home, Ms Watson said.

“When the Baillieus bought the building, they converted it into apartments, and these apartments were high-end accommodation for people like bachelors who wanted a place close to the city that was relatively low maintenance,” she said.

“It was one of the earliest apartment buildings in Melbourne. That was a phenomenon in a couple of places in the inner suburbs and was definitely influenced by what was happening in cities like New York, where apartment living was becoming more common.”

The Baillieus retained as many of the original features as possible in the refurbishment of the home to create the apartment block, which they named Cliveden Mansions. They also added a fourth storey to the structure, replacing the original home’s pitched roof.

The apartments opened in 1914.

Curiously, none of the 48 apartments had a kitchen. Instead, residents and their friends were offered the choice of eating in a communal dining hall or private in-room dining with a cooking staff led by a French chef.

The Cliveden Mansions were home to doctors, lawyers, executives and other professions that included High Court judges Sir Frank Duffy and Sir Isaac Isaacs, the latter going on to become Governor-General.

But as the decades passed, it became difficult to maintain the building.

In 1948, a broken water pipe caused flooding through much of the buildings. Residents’ belongings were lined up on the footpath as workers tried to stem the flow. By 1968, when the Baillieus sold it, Cliveden was doomed.

RELATED STORIES:

RISE AND FALL OF MELBOURNE’S MOST OPULENT ESTATE

1930s: PHOTOS REVEAL WHAT MELBOURNE LIFE WAS REALLY LIKE

MELBOURNE'S GRAND OLD BUILDINGS THAT NO LONGER STAND

“By the 1960s the building was not in very good condition. It was dilapidated and certainly not as it was in the early 20th century, and in 1970 it was controversially demolished,” Ms Watson said.

Cliveden made way for the Hilton Hotel, the brown brick tower than was an international-style hotel rival to the Southern Cross Hotel. The Hilton is known as the Pullman Hotel today.

“The Cliveden Mansions was one of those East Melbourne tragedies. It’s such a shame that it’s lost because East Melbourne is a very rich 19th Century cultural landscape with lots of buildings that represent architecture of the 19th and early 20th century, and Cliveden Mansions was an enormous part of that cultural landscape,” Ms Watson said.

“It was an interesting addition to the East Melbourne landscape and a very prominent building still today but many people still mourn the loss of Cliveden.”

The Cliveden name lives on in East Melbourne at the Pullman’s Cliveden Bar and Dining restaurants and the Epworth Cliveden Hospital.