Was ‘slug gate’ a slimy trick to divert public money?

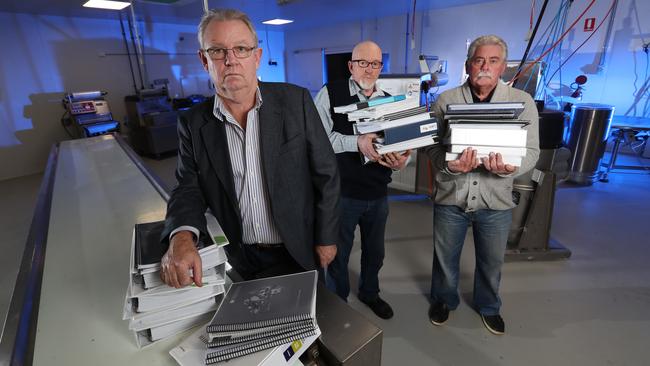

Victims of the unresolved “slug gate” saga have compiled a dossier which they say points to secret deals, dodgy financial records and police interference.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Planting a slug in a commercial kitchen might be a slimy trick, an act of sabotage triggering outrage. But what if it’s a clumsy misstep in a bigger game of backroom political operators diverting public money for their own ends?

That’s the intrigue now looming over a painstakingly ineffective police “investigation” of the Slug Gate scandal, so slow that some might call it stonewalling.

For Ian Cook, Slug Gate began when a Dandenong City Council health inspector planted a garden slug (a variety unknown locally) on the floor of the then thriving family business, I Cook Foods, in Dandenong.

That was on February 18, 2019. What happened that day was instantly amplified when the health department took draconian action over the contrived breach, wrecking a $25m business built over 30 years.

I Cook Foods had previously led the market in pre-packaged meals for hospitals and aged care homes in Victoria.

In doing so, it saw off a challenge from Community Chef, a government and council-backed enterprise launched ostensibly to counter job losses caused by the Global Financial Crisis.

The Community Chef concept was cooked up by Melbourne Labor councils and the State Labor Government, notably the then health minister, Daniel Andrews.

Community Chef cost taxpayers and ratepayers more than $30m, comprising $17.5m start-up funding, and cash injections adding $14.5m. Its state-of-the-art plant at Altona cost $24m.

The public paid for it but didn’t get much for their money.

Despite its featherbed of grants, Community Chef couldn’t compete with I Cook Foods and other private providers.

But its losses seemed more than could be blamed on lack of efficiency and quality control. The business overspent so heavily that it raised eyebrows and serious questions about governance.

Community Chef was launched in 2010. But by 2020 the business was haemorrhaging so much cash it was handballed to Victoria’s health department for a nominal $1 per share from each associated council — but with $6m in accumulated debts.

The business had bled out, losses so huge they demand questions about who stood to profit from the flood of runaway cash.

That’s the opinion of two former detectives who have prepared a 6000-page brief on the Slug Gate affair, and of lawyers now moved to advocate for the Cooks privately, as well as professionally, after being briefed to prepare a damages suit.

The former police officers, Rod Porter and Paul Brady, insist there is evidence showing that several people should be charged over the slug incident.

Instead, the State Government and councils — and Victoria Police command — have “pushed back” for three years.

This suggests the scandal runs deeper than a crude attempt to sabotage a thriving competitor.

Slug Gate might have been settled quickly if the state government had offered apologies and compensation for the actions of the health department under incoming chief health officer Brett Sutton, who effectively crippled the Cooks’ business overnight.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, the State Government doubled down, maybe believing it could wear down the Cooks. If so, it was wrong.

At best, the government has painted itself into a costly corner as the Cooks prepare a huge damages lawsuit. At worst, the clock is ticking on a time bomb that could make the Red Shirts scandal look like a Sunday School picnic.

The Cook group’s ongoing investigations point to secret deals, dodgy financial records and police interference.

The question they pose is whether the Government’s overly-aggressive stance is to mask a scheme that syphoned public money out of Community Chef into a political slush fund or private pockets, or both.

Health, education and aged care are giant budget items for governments, soaking up huge money across sprawling systems. As such, they are vulnerable to fraud.

The early planning for Community Chef was coincidentally around the time that fraudsters led by an inexplicably wealthy businessman and racing identity, John Capellin, was caught ripping millions from taxpayers.

Capellin seemed to have bottomless pockets to fund expensive racehorses, a “hobby” that ended up landing him the multiple Group 1 winner, Testa Rossa.

With former North Melbourne champion David Dench, Capellin and others were jailed for draining millions through bogus maintenance bills for Victoria University.

Capellin’s unexplained wealth fed speculation for a long time before the axe fell. The question was: Where did the money come from?

In the Slug Gate case, the question is: Where did the money go?

The Cooks’ investigators have evidence that honest police officers who worked on the slug investigation (until ordered off it), established that Brett Sutton and other health officials faced serious questions.

Sutton was formally promoted to chief health officer in March 2019, just weeks after taking the action over the slug “find” that destroyed I Cook Foods.

When the first lockdowns were announced a year later, this previously anonymous bureaucrat became the government’s public face of the pandemic. Meaning there were now urgent political motives to shield him from the Slug Gate backlash.

After interviewing Sutton in early 2020, Detective Sergeant Ash Penry made a briefing note which was swiftly suppressed by his superiors but later accidentally released to the Cooks when copied onto a hard drive they had supplied to police with information.

When the hard drive was returned to the Cooks, their IT expert found the briefing note embedded in the trash file.

Seeing the briefing note was lucky for the Cooks. It wasn’t lucky for Penry. He was transferred and told to keep quiet about what his investigation revealed.

Meanwhile, Penry’s record of interview with Sutton is in police files somewhere. So far, senior police have blocked efforts by lawyers to obtain it under freedom of information laws.

“They are not saying there’s no Sutton record of interview,” says Ian Cook.

“They are saying they can’t find it and, in any case, it’s not ‘in the public interest’ to release it.”

Cook’s lawyers have now lodged a subpoena to obtain the document they are confident has Sutton topping a list of officials implicated in Slug Gate. And Cook’s investigators are doing the investigation that police are not.

The Herald Sun is not suggesting Sutton has acted inappropriately, but that his knowledge about what went on in this case should be made public.

In January, one investigator went to a western suburbs address, tracing the destination of two payments made to separate entities by Community Chef.

The address was an empty warehouse. Neighbours said it hadn’t been used for more than six months.

But the payment of more than $20,000 to a faceless business in an empty warehouse is a small oddity in a case littered with bigger ones – such as Community Chef’s staggering cleaning bill.

Whereas I Cook Foods budgeted around $4000 a month to clean their food plant, Community Chef’s figures show cleaning costs of up to $20,000 a month. Even allowing for slightly larger premises, a monthly bill of $6000 would be generous – but three times that seems preposterous.

The phantom cleaning cost represents a “take” of around $150,000 a year. It’s not the only example of black holes in Community Chef’s operations.

The biggest mystery, by far, is the curious case of the missing $800,000.

A business of Community Chef’s size needs about $1m in reserve to ensure it doesn’t risk trading while insolvent. It had that amount but in 2019 asked Sutton’s health department to increase its drawdown facility to $1.8m – $800,000 above the sum actually needed.

If anyone knows a legitimate reason for the extra money, they’re not saying.

When Dandenong Council chief and Community Chef director John Bennie was questioned by a parliamentary inquiry last September, the master bureaucrat was his usual confident self right up until MP Georgie Crozier sucker punched him.

Why had Community Chef asked for an $800,000 drawdown in March, 2019, she demanded.

Bennie looked uncomfortable and evasive. He said it was “a long time ago” and that he had “no immediate recollection.”

Again, the Herald Sun is not suggesting Bennie was involved in any wrong doing, but he should have had the answers to Crozier’s questions.

In the eight months since, no one has improved on that answer. Meanwhile, Cook’s investigators are building a dossier on interesting links between a colourful senior police officer and Dandenong Council identities, two in particular.

The clock is ticking.