Victorian psychiatric patients’ grim fate in hellish 1800s hospitals

SOME were violent, others were alcoholics and many had little reason to be admitted at all. Patients of Victoria’s hellish psychiatric hospitals of the 19th Century tell their stories through old records.

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

SOME had a history of drinking, others were violent and abusive, and many had little reason to be admitted at all.

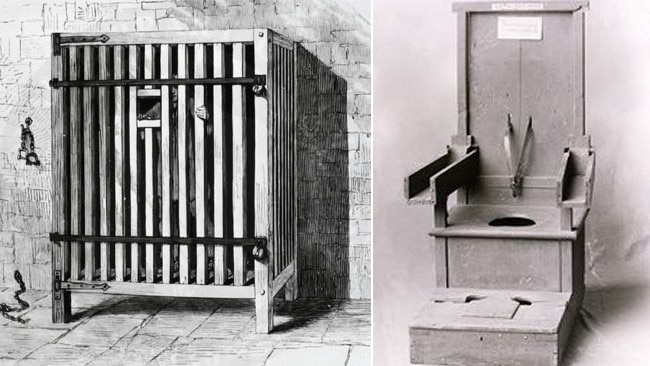

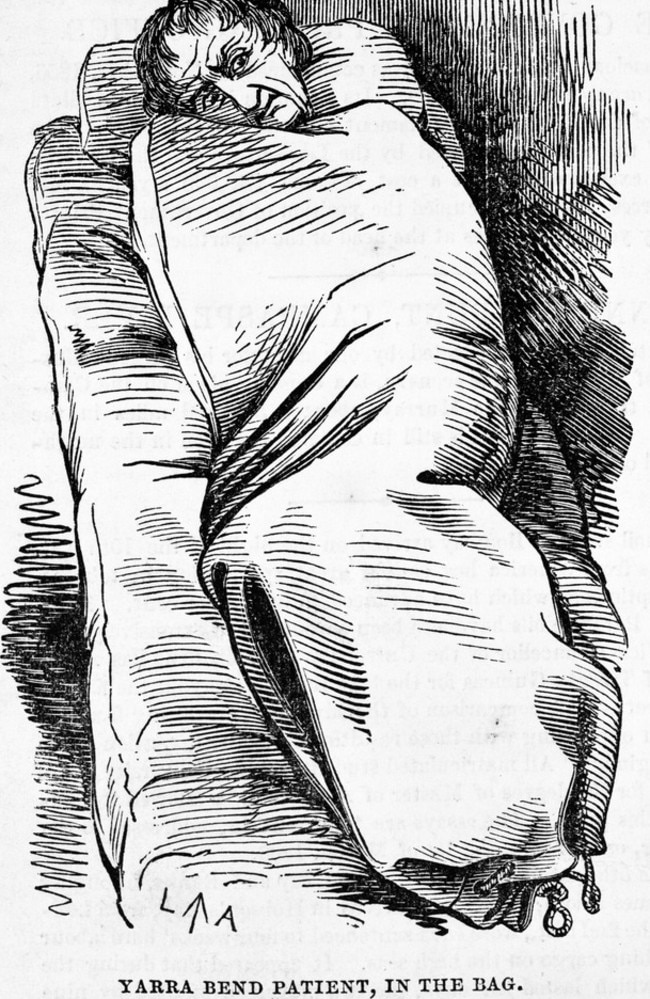

Patients in Victoria’s hellish psychiatric institutions of the 1800s were submitted to gruelling treatment including restraint bags, strapped chairs and soul-destroying isolation cages.

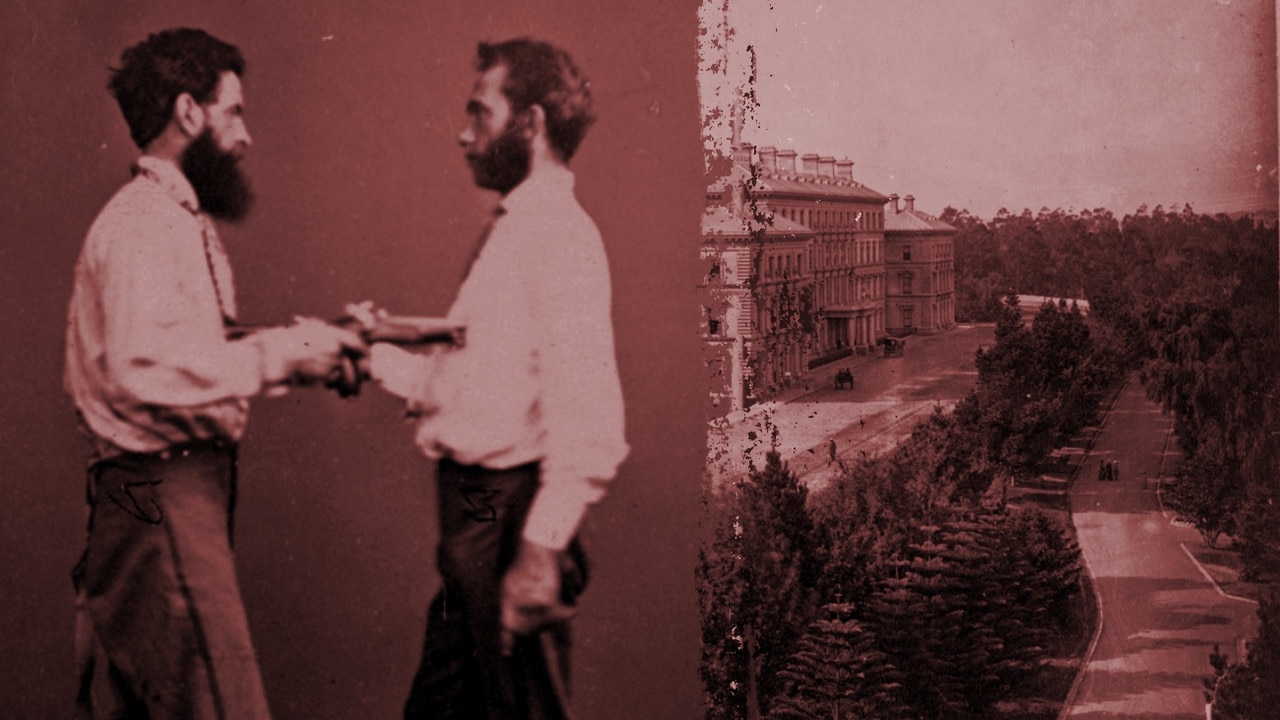

Hand-written case files, made available to the Herald Sun Department of Internet through Public Records Office Victoria, give a fresh insight into patients’ state of mind in a system that often saw people condemned for simply being different.

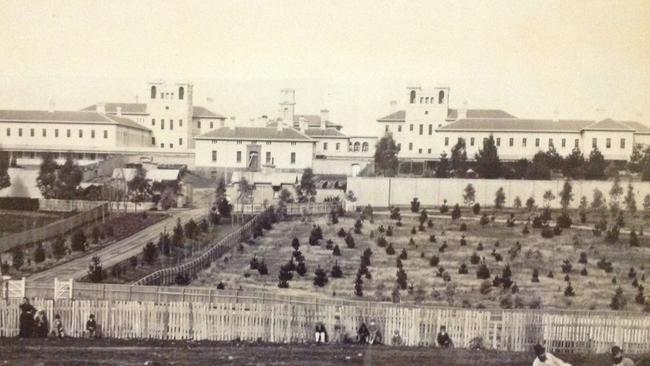

The Sunbury Lunatic Asylum was among several institutions, including Ararat, Beechworth, Yarra Bend and Kew, to house thousands of patients during and after the gold rush.

MORE: MELBOURNE’S CREEPIEST GHOST STORIES

TRUTH OR MYTH? MELBOURNE’S URBAN LEGENDS PUT TO THE TEST

It took just two signatures to have a person condemned to a psychiatric ward in a time when understanding of mental illness was desperately wanting.

In their own words, male patients at the Sunbury hospital describe how they came to be in the institution’s care.

The patients’ stories were taken down verbatim by a ward doctor, described by one patient as Dr O’Brien, who made notes over time about their progress and prospects for work and recovery.

None of the five men who gave the accounts below survived the asylum.

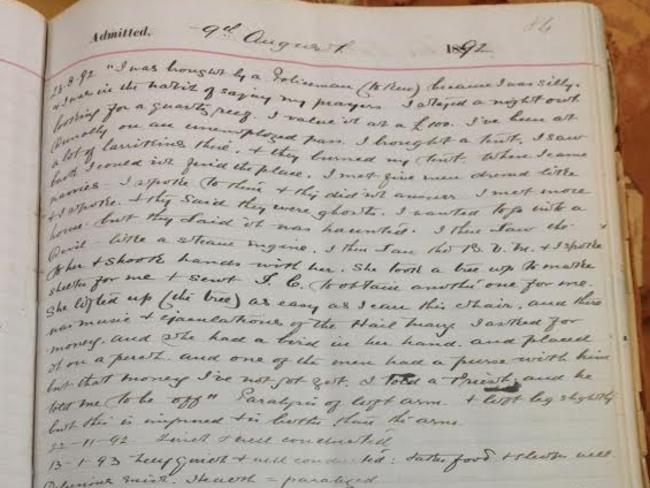

‘I met the devil’

Daniel Dooley, 59

23/8/1892

I was brought by a policeman because I was silly, and I was in the habit of saying my prayers. I stayed a night out looking for a quartz reef. I value it at 100 pounds. I’ve been at Dunolly on an unemployment pass. I brought a tent. I saw a lot of larrikins there, and they burned my tent. When I came back I could not find the place. I met five men dressed like navvies (Irish workers). I spoke to them and they did not answer. I met more and I spoke and they said they were ghosts. I wanted to go into a house, but they said it was haunted. I then saw the Devil — like a steam engine. I then saw the B.V.M. (Blessed Virgin Mary) and I spoke to her and shook hands with her. She took a tree up to make shelter for me and sent J. C. (Jesus Christ) to obtain another for me. She lifted up the tree as easy as I can this chair. And there was music and ejaculations of the Hail Mary. I asked for money and she had a bird in her hand and placed it on a perch, and one of the men had a purse with him but that money I’ve not got yet. I told a priest and he told me to be off.

‘Someone’s coming to kill me’

Timothy Shannon, 35

20/5/1892

My name is Tim Shannon. I was born in County Clare. I have friends out here — two in Melbourne. Pat Shannon lives in Dryden St South Melbourne and the other is Tom Shannon, a caster — in Carlton. I forget the name of the street. I suppose it is 3 or 4 years since I went there. You are Dr O’Brien — at least I’ve heard them call you so. I got frightened of the people outside going to kill me. I took it in my mind like that. I’ve got these ideas in my mind now. I think they try to injure me but I did not see them. I would like to get out. But I think he could not support me if I did not work. I used to take 4 or 5 pints of beer — I don’t sleep at night. I’m frightened at somebody coming to kill me. I am not strong enough to work.

‘I don’t know this place’

Will Robinson, 54

20/5/1892

My official name is Will Robinson — my correct name is Charles Hutton. I was born in 1833, I’m 54 years of age. I don’t know this place. I came from several places. I cannot tell where I came from last. I left Beechworth in 1854, 1855, this year is 1887. I was never in an asylum in my life. I’m not married. I have relations. I can hardly tell you where they are. I cannot tell you where one is. I see well.

‘I knocked her about a bit’

Patrick Malone, 43

27/5/1892

Paddy Malone is my name. I’m about 20 years of age. I do not know the year. I never kept count. I was sent to Kew owing to my mother’s fault. I was a bit wild. I was young. I might have been at fault. I was a bit wild, having a change like. My mother could tell you better. I was into drinking. I had a few words with my mother and sister like. It was 12 months ago. I cannot remember the words. I never saw spirits or heard voices — I was never bad like. It was only a row with my mother and sister. I was lying down and she wanted me to go outside and I would not. She got her hair off and I knocked her about a bit. It is a long time ago. I did not do much — if I did anything at all. I did practise “self abuse” but it’s a long time ago. I don’t do it now. I would be dead in a few days if I did any work.

Nathaniel Buchanan, researcher for Aradale Ghost Tours which covers the Ararat institution and the disused Mayday Hills Lunatic Asylum at Beechworth, said treatment in the mid to late 1800s was well behind modern practices.

“Treatment was mostly restraint,” he said.

“There were none of the modern medicines, that mostly came in the 1950s.

“Restraint would start with a straight jacket, if that wasn’t suitable the ‘lunatic’ could be placed in an isolation box until they settled down.

“There was no distinction between epilepsy and schizophrenia. In that time, there were four classifications for lunacy — mania, melancholia, dementia and paranoia.

“There number of conditions has increased from four to about 2000 since then.”

Mr Buchanan said conditions that are now understood were made to fit under one of the broad categories and treatments were often poorly applied.

“Many of the women in the institutions in the late 1800s were likely to have been suffering from post-natal depression, but that was just classified as melancholia,” he said.

“Also it took just two signatures for somebody to be taken in. If a man wanted his wife gone, and his friends knew about it, he could get them to say his wife was mad, and she’d be taken.

“At one stage it also took two signatures to be discharged, but that was later increased to eight signatures, meaning it was a lot harder to get out.”

Inmates at Aradale and Sunbury were given work in an 1800s movement towards “moral treatment” — teaching patients proper morals by giving them trades and responsibilities.

Women were tasked with sewing and washing while men made shoes and tended farms.

Acres of land surrounding the Ararat institution were dedicated to crops and the hospital was self sufficient.

But that didn’t make the institutions nice places to be.

Mr Buchanan estimates up to a third of patients who entered the hospitals never came out.

“You’d never want to end up in a place like this,” he said.