The WWI Diggers who found romance in Europe but never got to know their children

AUSTRALIAN Diggers left behind more than a legacy in Europe in World War I, with hundreds of soldiers fathering children who never met their Aussie fathers — and one Belgian family is still on a mission to find their long-gone ancestor.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ANZAC Day reminds us that wars threw up far more stories than ever will be told.

They keep surfacing the way the old bullet shells, shrapnel and bones do in the battlefields at Gallipoli and on the Western Front.

So many of them are love stories of some sort: often tragic, all touching.

ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE ANZAC DAY SERVICE

ONE THING YOU SHOULDN’T BRING TO ANZAC DAY CLASH

Four years ago, I visited a cemetery in the French village of Daours on the river Somme, in the green and peaceful valley that a century before was a vision of Hell — probably the most terrifying and deadly battlefield of human history, where my grandfather spent three years and returned a shattered man.

The idea was to gather stories of the children fathered in France and Belgium by the Diggers who fought there.

Little wonder those things happened: they were very young, most away from home for years, in a time and place where almost every local fighting-age male had been killed, injured or otherwise swallowed by the war.

The story of the Australian lieutenant’s Frenchwoman in Daours was one of many.

Lieutenant Alan Falconer of Malvern had joined up at age 19, leaving a sweetheart called Bessie Bowring to whom he would leave most of his deferred pay.

The boy officer survived Egypt and Gallipoli but was killed on Anzac Day 1918, 100 years ago today. He was 23.

Years later, Falconer’s brother Keith was in France on business and came to Daours to the war cemetery, yet to get the white headstones to replace the original wooden crosses.

Keith was surprised to see his brother’s grave much better kept than those around it. Each time he visited there were fresh flowers on it.

One day he asked an old Frenchman who it was that tended the grave and brought flowers. The man wrote a note in French and gave it to him.

WILL 102YO ANZAC MURDER-MYSTERY EVER BE SOLVED?

Keith found someone to translate. The message was subtle but clear. It said Alan’s grave was tended by a local woman accompanied “by a daughter who had never known her father”.

The broken-hearted Frenchwoman and her fatherless daughter are long gone. If the daughter was Alan Falconer’s child, as Keith always believed, she was one of hundreds left behind in France and Belgium by Australian soldiers.

“The Australians were heroes in the bedroom as well as in battle,” jokes Belgian historian Claire Dujardin, who has spent years following what she finds a fascinating subject — the connection between Diggers and those they defended against the Germans.

For Claire, the story is close to home. Her great-grandparents billeted two Australian soldiers at their house at Marchienne near Charleroi. The family were so fond of them that the stories told later about “les Australiens” caught Claire’s imagination when she was a child.

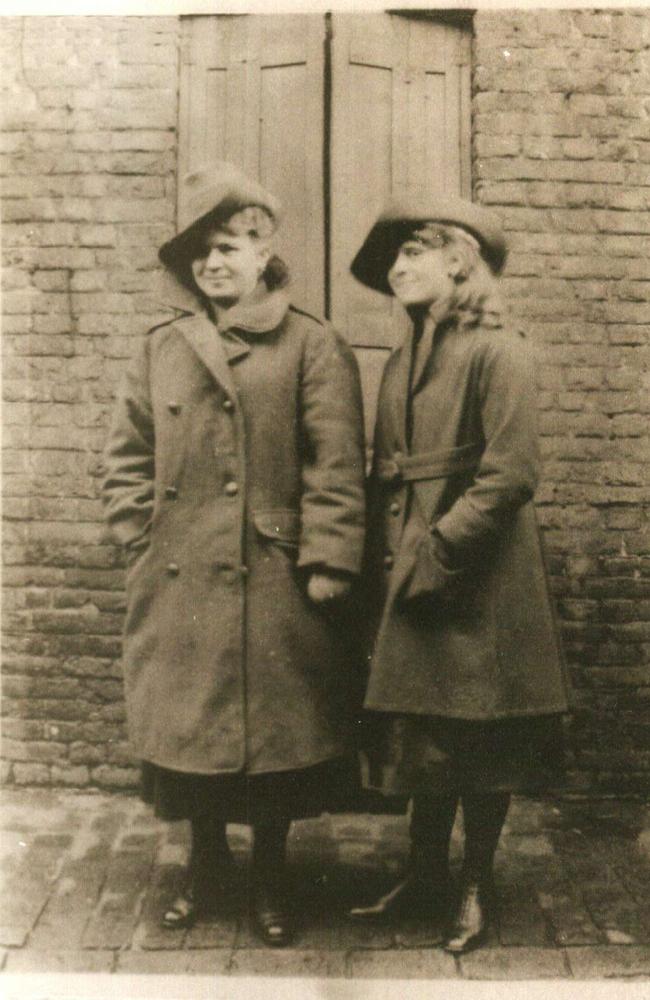

She still has a camp stretcher the two Diggers left behind. And she treasures a photograph of her grandmother and great-aunt as teenagers, wearing the Australians’ slouch hats and army greatcoats.

Claire Dujardin has discovered many hidden love stories while researching the history of Australian army units billeted in Belgium and northern France.

Now she is appealing to Herald Sun readers to help find Australian relatives of a Belgian man whose great-grandfather was a young Digger.

The part-Australian Belgian is Jean Van Campenhout, a postgraduate geologist who uncovered the family secret after the death of his own father, when he was bequeathed an AIF group portrait with one of the young soldiers, standing in the back row, marked with an X.

This man, Jean learned from older family members, was his Australian great-grandfather, who returned to Australia in March 1919 before the young Belgian woman he was courting even knew she was pregnant.

The Digger never knew that his son Robert was born on December 7, 1919.

The only clue — apart, perhaps, from the name “Robert” — is that the unknown soldier was in the 26th Battalion but probably enlisted originally in the 25th. He was billeted in Marchienne-au-Pont (near Charleroi) during the winter of 1918-19.

Records show that the 26th Infantry Battalion arrived there on December 20, 1918, so it was a whirlwind romance.

Jean Van Campenhout surmises that on Christmas Day and New Year’s Eve, the young soldier and his mates were invited to join in local family activities.

It seems likely the lonely Diggers would meet young women invited to a Supper Dance on the evening of New Year’s Day, 1919, the first of a series of entertainments run by the military over four months.

The battalion left the district in March and the last of them sailed for Australia from Le Havre by June. Among them was the young man who didn’t know he was to become a father.

Jean’s best chance of finding his Australian relatives is that someone has a copy of the same photograph, or a similar one, with the men’s names marked.

An amateur historian, Alison McCallum, who is helping the Belgians with the search, has pointed out a clue: the officer in the front row, third from the left, has a Military Cross ribbon.

She hopes that relatives of that MC winner — or other military history buffs — will recognise him in the photograph and so help identify others in the group.

Lest we forget.

LISTEN NOW:

ITUNES

RSS FEED

SALUTE TO ANZAC WOMEN UP FRONT

AUSSIE SOLDIER PLAYS BAGPIPES IN ANZAC FIRST

— Andrew Rule is a Herald Sun senior journalist