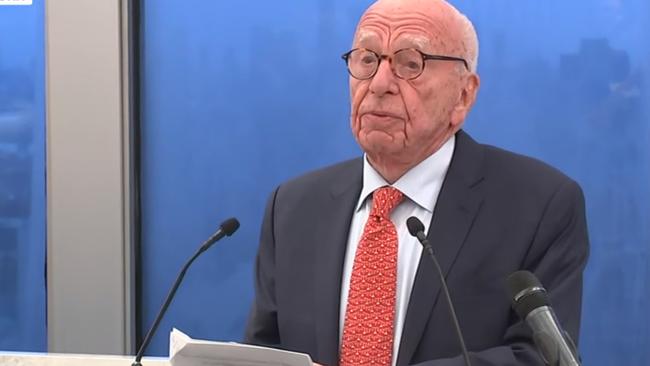

The trials and tribulations of Rupert Murdoch

Media mogul Rupert Murdoch flew to Melbourne in 1979 to make an odd purchase that would define his seven-decade journey to the top.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In 1979 Rupert Murdoch flew into Melbourne to try to buy an airline.

His decision to join the battle for Ansett, Australia’s then only privately-owned airline, its shares listed on the stock exchange — both our ‘national carrier’ Qantas and the separate TAA, the head-to-head domestic competitor with Ansett under the ‘two-airlines policy’, were fully government owned — might seem odd.

Only ‘odd’; are you kidding?

Murdoch was literally born into newspapers.

His father, the himself legendary Sir Keith Murdoch, of Gallipoli news-breaking fame had built the Herald and Weekly Times into the nation’s biggest and mightiest media empire.

Already himself, more than a quarter of a century into what would prove his own even more extraordinary journey across the global media landscape, trying to buy an airline?

Yet, it was all and only about media.

Murdoch, like no other businessman or entrepreneur one can think of, was prepared to buy an airline, purely and simply to get his hands on a single television station, and a struggling one at that: Melbourne’s then Channel O, now Channel 10.

How did a TV station end up inside an airline?

Ah, thereby hangs a tale that captures much about the ‘old Australia’ – the Australia back then, when both politics and business, right across the nation, were quite literally controlled out of the Melbourne Club, at the top end of Collins St in Melbourne, along with its sister ‘gentlemen’s clubs’ in Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide.

But it even more captures the essence of Murdoch, an essence that surfaces again and again, and again, in his 70-year journey out of Adelaide and ownership of just that single afternoon paper – his extraordinary, utterly unmatched, quite breathtaking, entrepreneurial risk-taking.

But always, also, as the outsider — seeking to and succeeding in, breaking into, and in turn, shattering, existing centres of entrenched business and media, and usually also linked political

power.

A reality, again probably surprising to a modern audience, taught by established media to see Murdoch as the ultimate insider.

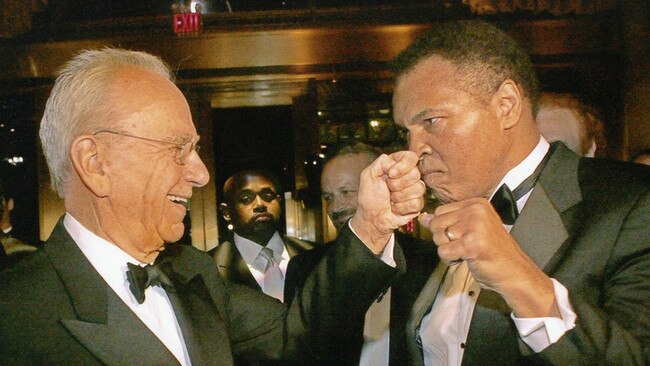

More fundamentally and more potently, his ultimate success in winning Ansett – crucially, in partnership, with Sir Peter Abeles and his TNT transport group – would prove in a way that not even Murdoch would ever have anticipated, to be the absolutely pivotal deal of his 70, or to be pedantic, 71-year journey.

A journey, that while not yet ended, is now seeing the formal handing of the reins to his son Lachlan; something that had been denied him on the death of his own father, back in 1952.

Now, back in 1979, the battle for Ansett seemed like just another one of the great and absorbing takeover battles, as it raged all through the year across stock exchanges in Melbourne and Sydney and in those days overnight in London as well.

It would ultimately be resolved with all the major players quite literally sitting around a table through a weekend at Murdoch’s Cavan property near Canberra, wrangling over who would buy and who would sell and at what price.

Names, that were then at the centre of business in Australia, but apart from Murdoch now all faded into history.

One perhaps not completely faded.

For apart from Abeles, they included the urbane young interloper from Perth, Robert Holmes a Court, who would himself rage across corporate Australia through the 1980s.

Indeed, Holmes a Court would shake the foundations of the Melbourne establishment with his all- but successful assault on Australia’s then and still biggest company BHP, locking horns with John Elliott of Victorian Liberal establishment and Carlton fame – both Carlton the football club and Carlton the beer.

And indeed would lock horns again with Murdoch in the titanic – and media structurally seminal – struggle for the H&WT.

In succeeding with Ansett in 1979 and, for Murdoch, gaining the real prize – the TV station – a whole series of events would be triggered.

They would see Murdoch, all-but single-handedly completely transform the entire media landscape, not just in Australia, but also in the UK and even more incredibly the entire electronic media and entertainment spaces in America.

For Murdoch personally and his News Corp, we can see, when we zoom out, so to speak, how Ansett proved so pivotal.

There was the near-30 years leading up to 1979; and then the explosion of activity and genuine company and industry-building entrepreneurship – the building, not the mere buying of businesses – across three continents, concentrated in the 1980s and 1990s.

In the three decades before Ansett, Murdoch struggled to get traction, to build out from Adelaide, and especially into Melbourne and Sydney.

He was up against the-then three great dominant media empires – the Fairfaxes and Packers in Sydney, and the mighty H&WT, sprawling across Australia out of Melbourne. They kept him at bay, thereby sending him first to London, and then into the US.

And then there was the 40 years after Ansett, and especially the dozen or so extraordinary, truly breathtaking, years from the mid-1980s, when he single-handedly remade media in Australia, the UK and the US.

It’s never really been appreciated, far less explained, how and why, those 70 years can be split into two halves and why they pivot around the great battle for Ansett.

And that furthermore, much of it can be sourced to the actual buying of the airline, even though he had no real desire to own an airline, only that he was prepared to buy it – the sheer breathtaking audacity that marked his every decade – just to get his hands on a seemingly marginal media asset.

The seeming prize, Ansett, was in 1979 still controlled and run by its legendary founder Sir Reginald Ansett, who would helicopter up each morning from his farm near Mornington to the Yarra landing pad, and then on to the head office at the top of Swanston Street.

But an Ansett whose grip was weakening: both physically – he would die in 1982; and also in terms of political support – his great mate and protector, long-term Victorian Liberal premier Sir Henry Bolte had gone, and the state was counting down to its first Labor government since the 1950s.

Now, in 1979, Murdoch was also in the early stages of plotting the execution of a quarter-century obsession.

This was an audacious and almost literally unbelievable takeover bid for the country’s biggest and most profitable and comprehensively dominant, and importantly, protected, media group: the sprawling Herald and Weekly Times (H&WT), built by his father.

His aim with the H&WT was simple and ‘very Murdoch’: to yes, take a huge step to finally gain a major presence in down under media, but also to reclaim what he saw as his birthright, denied him on the death of his father in 1952.

Sir Keith had built the H&WT into the nation’s media powerhouse, dominating first print and then TV in every capital city except Sydney, the home turf of the ‘old Sydney’ establishment Fairfaxes and the more recent, more thrusting Packers.

In 1979 it was that trio – a corporatist H&WT, a relatively hands-off & aristocratic’ Fairfaxes, and the decidedly hands-on Packers – which dominated media in Australia, in a way almost incomprehensible in our 2023 world of social media and streaming.

Certainly not Murdoch.

Back then, each empire was rolling in money, in slightly different ways.

The Fairfaxes had a lock on the three great classified advertising ‘rivers of gold’ – cars, real estate and jobs – with The Age in Melbourne and the Sydney Morning Herald.

The Packers had the eyeballs of ‘Middle Australia’ with the Womens Weekly magazine and the dominant Nine Network, and the advertising dollars that came with them – young Kerry Packer was flexing his power with World Series Cricket.

Similarly and even more so, with the H&WT, in every capital city except Sydney.

All three – Fairfaxes, Packers and the H&WT – had put up the same sign: Murdoch keep out. And for more than a quarter of a century they had very successfully kept him at bay, with more than a little help from friendly politicians in Spring and Macquarie streets and in Canberra.

In nearly 30 years, he’d struggled to grow out of that one newspaper – Adelaide’s afternoon tabloid, the News. Albeit, Kerry Packer’s father Sir Frank had sold him Sydney’s Daily Telegraph, believing it would send him broke.

And two of them – the Fairfaxes and the H&WT itself – would join to beat him off, when he did launch what would be the first of his two bids for the H&WT, just after winning Ansett.

In bizarre terms, Ansett would prove to actually be Murdoch’s media ‘breakthrough deal’ in Australia.

It gave him Melbourne’s Channel 0/10 to network with Sydney’s Channel 10, acquired in a share market raid, to go head-to-head against the Packer’s Nine Network and the looser Seven network across Australia of Fairfax and the H&WT.

They had all acquired their TV ‘licences to print money’ from Liberal governments in Canberra, ‘advised’ by fellow Liberal state governments in Sydney and Melbourne – handing them to the established print media groups, which incidentally were also ‘media mates’.

Murdoch would spend less than $100m buying the two Channel 10s. He would sell them for $850m in 1986, when ownership of every major newspaper and TV group would change hands in the orgy of deal-making in the closing days of the ‘decade of greed’.

All that had been further fuelled by then-Treasurer Paul Keating’s instruction that media groups had to choose between being “queens of the screen or princes of print” – itself sparked by Murdoch’s successful assault on the H&WT and the Hawke-Keating government’s approval of the takeover.

That $850m garnered from the sale of the Ten Network – ironically, to another, like Abeles, of the great wave of post-war entrepreneurial immigrants from war-torn Europe, Sir Frank Lowy who built the Westfield property empire – gave Murdoch a war chest for the H&WT, and the UK and the US.

The whole $750m profit was completely tax-free, as it was made before the introduction of the capital gains tax by the Hawke-Keating government.

But the great untold story of the Murdoch journey, is the way Ansett itself – what had only been, to Murdoch, a necessary means to a media end – would itself turn into a river of gold, through the 1980s.

It wasn’t the airline itself; and brutally that would all end in tears. First with the ruinous pilots’ strike at the end of the 1980s, and then the fall of Ansett itself, after its sale to Air NZ, quite literally as the planes flew into the World Trade Centre on 9/11.

For albeit, providentially, Murdoch had sold his News Corp’s half stake for $680m in 2000, just 18 months before 9/11 – and another handsome tax-free profit.

No, what made Murdoch and his News Corp – and Abeles and his TNT – huge sums through the 1980s, was a separate business that Abeles developed adjacent to Ansett.

Called AWAS – Ansett Worldwide Aviation Services – and 50-50 owned by News Corp and TNT but separate from Ansett, it built up an aircraft leasing business, at precisely the time global passenger travel and international freight business exploded through the 1980s.

AWAS poured huge sums into News Corp, providing the financial foundation for the extraordinary, breathtakingly entrepreneurial things that Murdoch would do in the UK and the US – after starting with the successful acquisition, at his second try, of the H&WT in 1986.

Between that and the foundation of the Fox News Channel in 1996, we saw a decade of

entrepreneurial business-creating risk-taking across three continents by Murdoch, the like of which we had never seen before in the 20th century.

It was a business risk-and-success saga of such mammoth scope, starting in 1986 with Murdoch’s audacious move – and it was, truly audacious – to take over the H&WT, the group built and run by his father Sir Keith until his death in 1952 from a heart attack.

Given the impression today of Murdoch’s News Corp – publisher of this paper – as the dominant mainstream media player in Australia, aside from the taxpayer-funded ABC monolith, it’s worth emphasising that back in 1986 Murdoch was in fact very much the struggling outsider.

Back then, media in Australia was dominated by the Packers, Fairfax and most of all, the H&WT.

A H&WT, grown lazy and somnolent through three decades of easy domination in Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth.

Sydney’s family-controlled John Fairfax, riding super-rich on its “rivers of gold” classified advertising.

And Kerry Packer’s all-dominant Nine FTA-TV network – in a down under world of no Pay-TV and certainly no streaming; Apple’s iPhone was 20 years into the future – and its equally rich portfolio of magazines headed by the Women’s Weekly.

In 1986 Murdoch’s News Corp was a distant fourth. And to win the HWT he had to fight off both Fairfax and the decade’s wiliest entrepreneurial wheeler-dealer, Holmes A Court.

Yet at the very same time, Murdoch was embarked on what was probably his most ambitious and riskiest move of all – establishing a fourth FTA-TV network across America to take on the powerful incumbent trio of NBC, CBS and (their) ABC, all of whom had been entrenched since the 1940s.

This was and is Fox Broadcasting – a FTA-TV network like Nine and Seven, very different from and separate to Fox News which came a decade later on Pay-TV.

Yet, almost without drawing breath, Murdoch would move in 1989 to launch the satellite Sky Television service in the UK.

Again it had to compete with the entrenched power of the BBC and its sole FTA-TV competitor ITV. It also had to fight head-to-head with British Satellite Broadcasting which had won the official licence to start Pay-TV in the UK.

Ahead of that had been his purchase of the UK Times newspaper group and his move to bring UK newspaper production processes into the 20th century.

It was a move – and a quite literal, in the streets, battle – that he, coming as an outsider into the cosy world of Fleet Street, was daringly prepared to do all on his own; that all the other media groups would beneficially follow when he ultimately won; and which would enable them all to survive into the 2st century and the coming digital onslaught.

It was a success, incidentally, helped in no small way by the trucks from Abeles’s TNT transport group getting the papers through the union blockades; one tangential benefit from the partnership forged over Ansett.

Just let all that sink in.

Here was somebody embarked on three massive, hugely risky, business-building – or, breaking – moves, from the ground up, and as a complete outsider in two cases, across the world: in Australia, the UK and the US.

Three huge, risky – literally betting-the-bank – ventures; and all, at the same time.

Furthermore, in each case it was against entrenched and far more powerful and profitable incumbents.

And yet all three of them succeeded; and not only succeeded, but forced massive change across the respective media landscape.

The risk was breathtaking; and Murdoch had also to survive Paul Keating’s 18 per cent interest rates and the recession we supposedly had to have. Which he did, narrowly, through some teeth-gritting days of bank negotiation.

In the UK, after both Murdoch’s Sky and its opponent BSB lost billions, it was BSB that sued for peace and merged with Sky; with Sky and Murdoch coming out in control.

While Fox in America clawed its place as the fourth national FTA-network – something that no American entrepreneur had tried to do in 40 years, far less succeed.

Along the way, it was Murdoch’s Fox that changed forever sports broadcasting in particular. In

America. In Australia. And indeed the world.

Oh yes, and in 1993 Murdoch also launched Pay-TV in Australia with Foxtel. And then came Fox News in 1996 – taking head-on the entrenched seemingly impregnable position of CNN which had become almost a generic term for cable news.

To me, the truly astonishing aspect is that when Murdoch launched on this most extraordinary

decade of entrepreneurial innovation and breathtaking risk-taking and, ultimate success, he had

already been on his restless journey for 34 years, going back to an almost pore-history time of 1952.

And then after the end of that extraordinary decade, there would be another quarter century to

come. A period, that would see the consolidation of the global electronic media operations in Fox and the US, UK and Australian print in News Corp.

It would lead, albeit, on to the clear-eyed acceptance of the new 21st dominant reality of Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon and Netflix.

Murdoch looked that reality in the face. The decision was brutally simple: he had to get bigger, much bigger, or get out.

The decision: to – partially – get out. He faced up to selling the UK Sky news operation to American media group Comcast and Fox’s Hollywood film and TV business to Disney.

Murdoch sold the Fox assets for $US70bn ($100bn) and the 39 per cent controlling stake in Sky UK for £12bn ($23bn).

The timing and the prices would prove to be exactly right, as the digital blitzkrieg rolled up,

decimating the value of the sold assets.

The whole of Disney today is worth just $US150bn, and struggling. Sky UK has lost at least half its value compared to the 2018 deal price.

That Murdoch journey is now consolidated in the US, the UK and Australian print operations and real-estate advertising business in News Corp; and the Fox TV Network and Fox News Channel in the separate Fox arm.

That incredible 71-year Murdoch saga now plays out in living real-time in the formal handover to Lachlan.