Tears, cheers and jeers: Why 2023 seemed a pivotal year

In 2023 we lost old favourites and found new heroes, were horrified by war and bemused by politicians — and AI began to rewrite much of what we thought we knew. Patrick Carlyon looks back at a tumultuous year.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There’s no going back.

That’s the prevailing message of 2023, when a war broke out and a technology began to rewrite so much of what we thought we knew.

Over the past 12 months, celebrities died and politicians disappointed. A referendum failed and a soccer team soared. A prime minister dithered and a premier vacated his perch for the lure of books and golf courses.

These are the sorts of touchstones that can shade any moment in time.

But the past year seemed more pivotal than most.

The Middle East can no longer be the same.

In conflict, after so many lives lost, the hopes of the past in the region cannot sate the demands of the future.

The West appears to be crumbling, largely out of America, where a proven buffoon and affront to history, Donald Trump, hopes to recapture the power he once applied so clumsily.

More so, the once marginal voice of the hard left, where the prescribed battlelines pit the oppressed against the oppressors in a never-ending campaign to be the biggest victim, entered the mainstream.

More profoundly, the unquestioned sanctity of human reason, creativity and imagination are now marked against the promise of something superior.

The takeaway from 2023 feels like a niggle that won’t go away. Assumed fixtures got reassessed. Doors opened, but in part because doors also closed.

We had been blooded for uncharted journeys by the recent pandemic. This passed, thankfully. Yet the bigger events of 2023 may not fade so neatly.

The embodiment of our brave new world is called Sam Altman. He’s calm of manner and nerdy of demeanour.

No one had much heard of him four years ago, when he started a little business called OpenAI. Yet when Altman was sacked, then reinstated, as head of OpenAI in November, he was being called the new Steve Jobs or Bill Gates.

The Californian is a new breed of Oppenheimer, just in sneakers and casual pants. Technology happens because it is possible, J. Robert Oppenheimer once said, as Altman repeated to the New York Times.

He is developing artificial intelligence that will change the world, either with untold wealth and prosperity or to end it altogether, according to a wide spectrum of expert views.

Already changing workplaces, AI could solve climate change or cure cancer. It could also, some say, turn humanity against itself.

In March, 1000 AI experts and industry leaders asked Altman and others to stop developing AI until the risks were better understood. Altman agreed that dangers lurked, but not anytime soon.

Others disagreed. “You need to imagine something more intelligent than us by the same difference that we are more intelligent than a frog,” said Geoffrey Hinton, a so-called godfather of AI technology who stopped working on the technology because of the risks he perceived.

Gulp. Ribbit.

Premier Dan Andrews left politics in grand final week, briefly distracting the half of Victoria not on the Collingwood bandwagon.

His call, though speculated upon for many months, took most observers by surprise.

He had easily won three successive elections, starting in 2014. Now he would consider vocations outside of politics.

Andrews, the most divisive Victorian leader since Jeff Kennett, would then get spotted much as a departed Elvis once got sighted.

The ire he still inspired at year’s end still shows no sign of dimming.

Jacinta Allan replaced Andrews, and vowed to push on with controversial major infrastructure projects, despite the state’s record debt. The state opposition, as usual, declared new wars against itself.

Allan had been the minister for Commonwealth Games delivery when the event was cancelled by Andrews in July. That decision humiliated a state that prided itself on big events, and outraged shocked stakeholders.

In the ensuing parliamentary scrutiny, the supplied answers did not satisfy those Victorians who were paying half a billion dollars or more not to stage something.

The Yes crowd of the Voice to Parliament, meanwhile, will be counting costs for years.

They could not agree with one another, much less the more than six in 10 who eventually supported the No case in October.

The Yes camp sold the Voice as a big deal that was not a big deal at all. It couldn’t properly explain what the Voice was and was not. Was it a solitary change or the first of three developments that would climax with treaties and possible reparations?

The Yes campaign was blighted by fragmenting within, as well as a haughty disregard for scepticism. It confronted a typically Australian reluctance to support anything that confuses and intimidates. So-called “racists” were found under beds, much like communists in the 1950s.

For the believers, the referendum loss represented another closed door. No Voice, or version of it, will hold unified appeal for years to come.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese wore sloganised T-shirts, as if he was an invested observer, during the campaign. He had seemed unwilling or unable to articulate his vision for constitutional change.

People fretted most about interest rate rises and the cost of living, and sneered at helpful Reserve Bank hacks (eg, “work more, spend less”) for balancing the household books.

Throughout, at times, Albanese seemed absorbed by geopolitical abstractions and energy infrastructure projects.

These massive builds, amid ambitious renewable energy targets, may revolutionise how we will receive power in coming decades. Getting guaranteed power this summer and the next seems almost as fraught.

Albanese appeared absent even when he was not criss-crossing the globe to meet leaders who included China’s Xi Jinping and the US’s Joe Biden.

He seemed flat in his response to the October 7 massacre in Israel. More spectator than statesman. Like many of us, perhaps, in what seems to be a growing trend, Albanese appeared to check out for Christmas long before December 25.

When the High Court ordered the release of 148 refugees in detention, including a rapist, killer and a pedophile, the Albanese government acted surprised. Fears compounded when six or more of the detainees would be arrested, including one charged with indecent assault.

History repeatedly knocked on Albanese’s door in 2023. He sometimes seemed to be elsewhere. As was his take on the year, in a recorded message, which mentioned neither the Voice nor hateful protest slogans.

Australia mirrored other Western centres in the rise of anti-Semitism. The chants began in Sydney streets on the day after more than 1200 Israelis were killed, raped and butchered in a Hamas strike that doubled as a first chapter in genocide.

An odd thing happened. Calling out evil might ordinarily seem like a safe response. But the clarity of condemnation for Hamas got muffled in the surge for the pro-Palestinian cause.

Sleeper passions and prejudices were further triggered by the inevitable Israeli response against Hamas. That this was a fight to a death, whether it be Hamas or Israel, became clouded in the carnage of collateral casualties in Gaza.

That Hamas held hostages sometimes got lost in the rhetoric, as did the Hamas practice of burying posts under hospitals and schools.

Calls for an Israel ceasefire got conflated with anti-Jewish rhetoric.

Some teachers and journalists forgot their professional hats.

Some unions, and the Greens, dusted off ideological tracts that would be considered unacceptable if applied to any other country or racial group.

Some local councils grandstanded by passing motions to boycott Israel companies, and never mind that Jewish children and students no longer felt safe in their schools or places of worship.

The messaging became distorted, piles of blind mantra sugared in John Lennon-dreaminess; that some government ministers, apparently mindful of their Muslim constituencies, did not call out the excesses brought into question the integrity of their convictions.

Australia was still grappling with the unprecedented turbulence at year’s end. By then, ignorance and political expedience had hijacked the discussion. Reasonable people, whatever their views, may have wondered if the Western world and Australia had gone out of its mind.

Who were the victims here? And if a Palestinian state was to be belatedly recognised, would the countless activists who have demanded such sovereignty also rally to defend its Stone Age pillars of misogyny, inequality and intolerance?

By some measures, the deaths of five people in an underwater submersible in June was the year’s most captivating story.

Observing the wreck of the Titanic on the Atlantic Ocean seabed is the preserve of wealthy “tickers” – people who adventure by virtue of their credit cards.

Yet the final moments of those people in the Titan submersible tube provoked a visceral horror for anyone who has ever shied from small spaces.

Contact was lost with the craft almost two hours into a four-hour descent of 4000m. An international search began when the craft did not resurface at the scheduled time.

Were they dead before they knew it? If not, could they be rescued before the oxygen ran out in three to four days?

Detected tapping sounds offered slight hope, before surface debris confirmed the tragedy four days after the craft’s descent.

A “catastrophic loss of pressure chamber” was the official term, amid hardening condemnation for Stockton Rush, the company head who himself died in the accident.

In Gippsland, a little story about a little lunch would engross the wider world. Like the Titan, its news appeal transcended its significance in the broader scheme.

A woman cooked for her ex-husband’s family and friends; three of them then died, and another spent eight precarious weeks in hospital.

Erin Patterson, who was later charged with murder, conjured the ghosts of Typhoid Mary and Lindy Chamberlain. A single question drove barbecue chatter: Had she deliberately poisoned her guests with death cap mushrooms in the beef wellington?

The Matildas dazzled us at the Women’s World Cup so much that Queensland premier Annastacia Palaszczuk promised a statue in honour of the team’s mighty but ultimately unsuccessful tilt. The full impact of their endeavours, the little girls who now want to be like Sam or Steph, may take decades to blossom.

Collingwood, meanwhile, trumped Brisbane in one of the most memorable grand finals.

Our cricketers retained the Ashes, in a series suitably laced with rancour, then upset expectations (and the Indian stadium crowd) to defeat India in the World Cup.

In an unlikely pairing, Australians rushed to watch Oppenheimer and Barbie in the same-weekend cinema release. Time magazine declared a singer, Taylor Swift, as the person of the year (nudging out Barbie), in a choice that seemed more about marketing than influence.

Comic genius Barry Humphries, 89, passed away in Sydney in April, prompting a universal outpouring of admiration and affection. King Charles ventured that “no one was safe” from Humphries’ onstage humour.

The disgraced Rolf Harris died more quietly. Hollywood TV star Matthew Perry died after a long and candid battle with drugs. The world also farewelled Sir Michael Parkinson, chef Jock Zonfrillo, artist John Olsen and singer Renee Geyer.

We were reminded of the power of a defamation court case to damage anyone trapped in its glare.

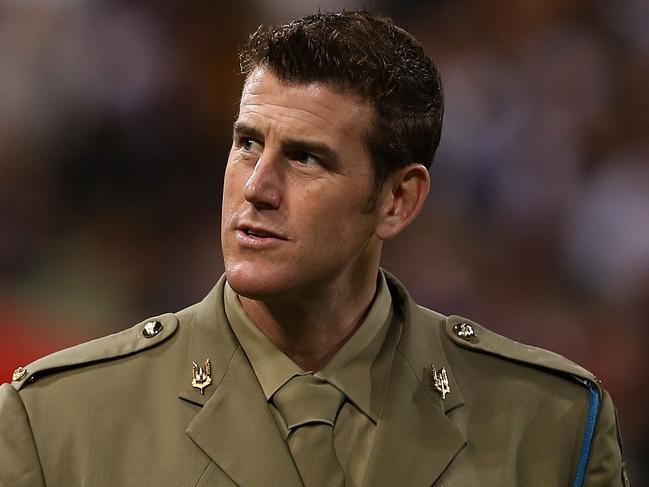

Ben Roberts-Smith VC took Nine Entertainment Co to court for defamation. He walked in a war hero and walked out, at least in the public’s thinking, a war criminal. He was found on the civil court’s balance of probabilities to have been complicit in the murder of four unarmed prisoners.

Accused (and unconvicted) rapist Bruce Lehrmann instigated a defamation trial against some media outlets. The most weaponised political scandal of modern Australia would be further muddled by curiosities of information teased out like plot points of a sorry political thriller in a Sydney courtroom. He was grilled for days; so was his accuser Brittany Higgins, who confronted painfully precise demands for detail.

Higgins told the court that she had awoken early in the hours of March 23, 2019 to find her colleague sexually violating her. They were in the office of the then defence minister Linda Reynolds.

As 15,000 or more people watched the trial online, she also spoke about her $2.44m payout from the commonwealth.

Everyone has a view on what happened that fateful night; everyone, too, seems to have a view on the process, or seeming lack of it, that led to Higgins’ taxpayer payout.

This epic of plays, a catastrophe of self interests, political overreach and Shakespearean agendas, will seep into the New Year.

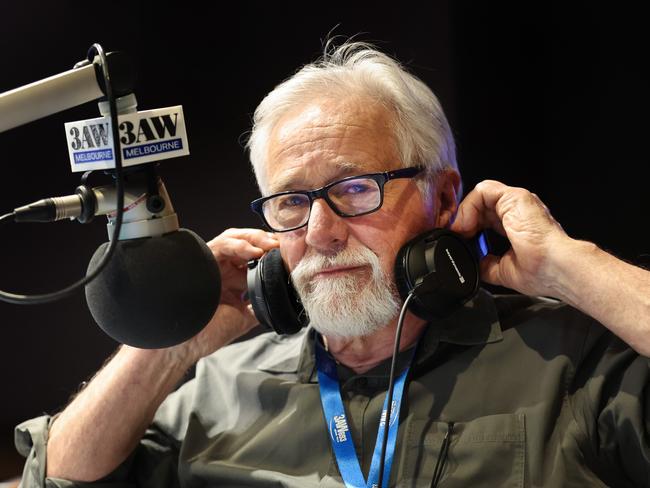

Neil Mitchell bowed out of 3AW morning radio after 34 years, almost always on top. Another public fixture, Alan Joyce, left Qantas after 15 years in charge, leaving a legacy of corporate bastardry to rival the big US change agents, such as Chainsaw Al Dunlop, of the 1980s.

His name is now a dirty word. The High Court found that Qantas had illegally sacked 1700 workers. The company was charged with selling tickets for flights that had already been cancelled. Officialdom joined customers in declaring Qantas loyalty programs to be extortionist.

Joyce receded to his homeland, Ireland, to be barely glimpsed since, albeit with a final-year payout of at least $21.4m.

Optus’s Kelly Bayer Rosmarin resigned after the second inexplicable company fail in little more than year. Optus services dropped out on November 8, affecting school exams and health services.

Rosmarin and her company couldn’t – or wouldn’t – explain what had gone wrong and when it would be fixed (after 13 hours).

As someone said, given Rosmarin’s response lacked empathy, or indeed authority, the public felt “ghosted” by Rosmarin throughout.

Rosmarin and Joyce are now case studies in how not to conduct big business.

Climate change, the Ukraine war, and a slavish adherence to renewable energy targets all got lost in the bigger stories of 2023.

They didn’t go away; they just got overshadowed by urgent events that may come to redefine who we once were and who we will become.