Stem cells injected into brain of Victorian patient in world-first Parkinson’s disease treatment

MELBOURNE surgeons have injected stems cells into a man’s head in a world-first trial to treat a disease with no known cure that affects 10 million people. Here’s what it means.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Stem cells regrow knee cartilage in world-first Melbourne trials

- Are stem cells the medical cure-all of the future?

- Cerebral palsy hope: Melbourne stem cell newborn brain injury trial plan

STEM cells have been injected into the brain of a Victorian patient as part of a world-first trial to treat Parkinson’s disease.

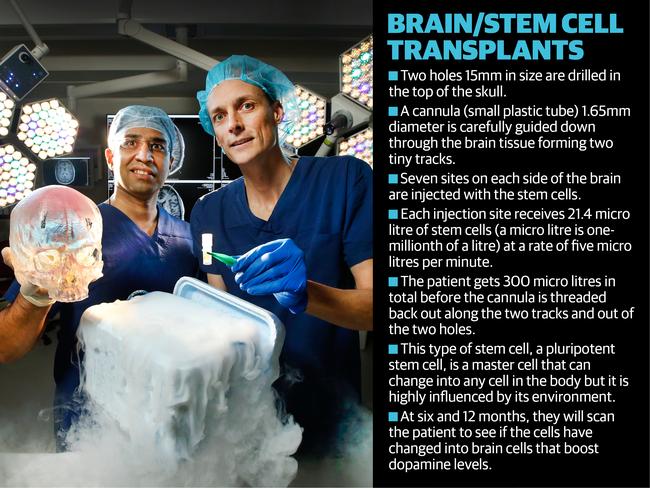

In experimental surgery, Royal Melbourne Hospital neuroscientists transplanted millions of cells at 14 injection sites via just two 1.5cm holes in the skull.

The cells, which can metamorphose into brain cells, had been frozen and flown in from the United States, in a global collaboration.

It is hoped the cells will boost levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine, a lack of which causes tremors, rigidity and slowness.

The therapy, which pushes the frontiers of science and surgery, had shown great promise in preclinical trials, paving the way for human trials.

The identity of the patient, 64, remains private while he recovers from the pioneering surgery.

Months of planning, which involved designing the operation from scratch, winning regulatory approval, and importing a machine that has never been used in Australia, was required.

Using a three-dimensional model of the patient’s brain, neurologist Andrew Evans and neurosurgeon Girish Nair spent weeks doing “dummy runs”, devising a way to enter the brain.

Hospital staff donated their time for the eight-hour operation.

ARE STEM CELLS THE MEDICAL CURE-ALL OF THE FUTURE?

CEREBRAL PALSY HOPE: MELBOURNE STEM CELL NEWBORN BRAIN INJURY TRIAL PLAN

STEM CELLS USED TO REGROW KNEE CARTILAGE IN WORLD-FIRST MELBOURNE TRIALS

Using the imported machine, the doctors travelled deep into the brain, making tiny tracks in the delicate tissue with cannulas to reach seven target sites on each side of the brain, leaving only a small surgical footprint.

A minuscule quantity of cells was implanted at a precise rate, totalling 300 microlitres.

Risks include paralysis, stroke, or death. If the cells escaped into the spinal fluid they could be lost; if they were injected too slowly they could become stuck; or they could grow rapidly into a tumour.

The surgery used pluripotent stem cells, which can change into any cell in the body. But being highly susceptible to their environment, “peer pressure” influences their transformation.

Dr Evans, the trial leader, said: “The idea with cellular replacement therapy is to be able to implant cells that will differentiate or change from stem cells into cells that either produce dopamine or provide other forms of support to remaining neurons.”

The unique treatment uses neural stem cells, derived from unfertilised eggs manufactured in a laboratory by the International Stem Cell Corporation in the US.

“Eventually we hope that we can use our therapy to cure Parkinson’s disease,” the ISCC’s chief scientific officer Russel Kern said.

The team did a scan 24 hours after the operation and were relieved to discover all target sites had been reached without complications.

The patient recovered quickly and was discharged within 72 hours.

No drugs have succeeded in stopping the progression of Parkinson’s, which affects 10 million people worldwide, and treatments for symptoms eventually become ineffective.

It is not yet known if the treatment has been successful, and a cautious Dr Evans said the trial first had to determine its safety. Eleven more patients will now have the surgery.

Final results will be known in two years.

———————————————————

BRAIN REBOOT: HOW THEY DID IT

IT must have been a strange sight on the flight: millions of tiny cells frozen in vials.

For such small substances these stem cells had big hopes resting on them.

They were making the long journey from a laboratory in the US to Australia to their new home- deep inside the brain of a Victorian man.

Their role was to star in a radical world-first surgery aimed at developing a new treatment for Parkinson’s disease.

At the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Parkville, neuroscientists had spent months planning for their arrival.

Armed with data from pre-clinical trials, trial leader and neurologist Dr Andrew Evans knew stem cell transplantation had shown great promise, but the biggest test in any trial is always translating the research from the lab to the bedside.

Dr Evans had been approached by the American company who developed the therapy because of his reputation, the hospital’s rich history of neuroscience research and its frustrations with overseas regulatory bodies.

Pushing the boundaries of science and surgery never comes without resistance. Fortunately that's where Australia’s expertise in medical research came into it’s own.

After negotiations with the Therapeutic Goods Administration and hospital ethics committee, Mr Evans and neurosurgeon Mr Girish Nair were poised to find a patient.

Although people afflicted with the degenerative neurological condition are desperate for new treatments because all existing medications eventually lose their effectiveness, the duo needed to make sure that the patient knew the experimental nature of the trial.

Finally, they found a 64-year-old Victorian man who would be the perfect patient.

Unable to ‘practice’ the surgery before the big day, the duo built a three dimensional replica of his brain.

It allowed them to devise a way to enter the brain via just two 1.5cm holes in the skull and reach all 14 injection sites.

A machine that has never been used in Australia was imported and permission was sought and granted to use it in the operation.

They travelled deep into the brain with their cannula, making two tiny tracks in the delicate tissue, allowing them to reach their targets: seven on each side of the brain.

An operating theatre was booked for a Sunday with staff donating their time for the eight-hour surgery.

What could go wrong? Nothing. A little. Or a lot.

“The site is very close to the brain stem - the most critical part of the brain - and if you poke around in the wrong places then it could end in paralysis or death,” Mr Girish said.

“And if you have a bleed there, even a small one, it’s a major stroke.”

Just injecting foreign cells into the brain tissue posed a risk. Where would they go? And what would they change into?

They used pluripotent stem cells, which can change into any cell in the body, but they are also highly susceptible to their environment as ‘peer pressure’ determines what they change into.

It’s hoped that this therapy will replace or boost levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine, a lack of which causes tremors, rigidity and slowness in patients.

“The idea with cellular replacement therapy is to be able to implant cells that will differentiate or change from stem cells into cells that either produce dopamine or provide other forms of support to remaining neurons,” Mr Evans said.

But there is always an element of the unknown: what would occur when they injected the stem cells into the brain?

If the cells escaped into the spinal fluid they risked losing them all.

If they were delivered too slowly they could become stuck and never reach their target.

Or they could grow unchecked in the brain, turning into a tumour.

Only 1-2 per cent of the transplanted cells will become dopamine, but preclinical studies show that only 10,000 cells need to change to make a meaningful difference so their dosage factored this in.

The amount injected was minuscule: one millionth of a litre is a micro litre and the patient received 300 micro litres of the cells.

Even how quickly the cells would be injected was calculated and recalculated until they were confident they had the rate of delivery just right.

It was with enormous relief when the team scanned the man’s brain the day after surgery and discovered they had reached all their target sites.

“Despite the long and complex surgery, we left a very small surgical footprint,” Mr Evans said.

While they won’t know if the stem cell transplant has been a success for some time, the patient recovered quickly and was discharged within 72 hours.

He will undergo scans at 6 and 12 months to check how the cells have settled in.

The therapy is unique because it uses parthenogenetic neural stem cells, which are derived from unfertilised eggs and manufactured in the lab by the International Stem Cell Corporation, a biotech company in California.

This type of stem cell avoids the ethical dilemma that often surrounds these types of endeavours.

“Stem cells therapy is a very novel field, but eventually we hope that we can use our therapy to cure Parkinson’s disease,” its chief scientific officer Russel Kern said.

Keen to avoid disappointing Parkinson’s disease patients, Mr Evans pointed out that this trial is to determine if the treatment is safe.

“I understand the expectations that people have, if I knew this was a cure then we wouldn’t be going to all this effort to test it.

“It’s a trial and you are allowed to hope for the best, but not expect it.”

Over the next year 11 more patients from around Australia will have the surgery at Parkville hospital, but the results will not be known for at least two years.

———————————————————

MORE: ARE STEM CELLS THE MEDICAL CURE-ALL OF THE FUTURE?

CEREBRAL PALSY HOPE: MELBOURNE STEM CELL NEWBORN BRAIN INJURY TRIAL PLAN

STEM CELLS USED TO REGROW KNEE CARTILAGE IN WORLD-FIRST MELBOURNE TRIALS

lucie.vandenberg@news.com.au