St Kilda great Nick Riewoldt shares the highs and lows of his career

SAINTS legend Nick Riewoldt reveals the devastation of the ‘St Kilda schoolgirl’ scandal and the two things he’d do differently if he had his time again. Read the exclusive book extract.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ST KILDA legend Nick Riewoldt led a rewarding life as an AFL captain, husband and father. But his world crumbled after reports of a sex scandal and his sister’s shock health diagnosis. Read three exclusive parts of his new book The Things That Make Us here.

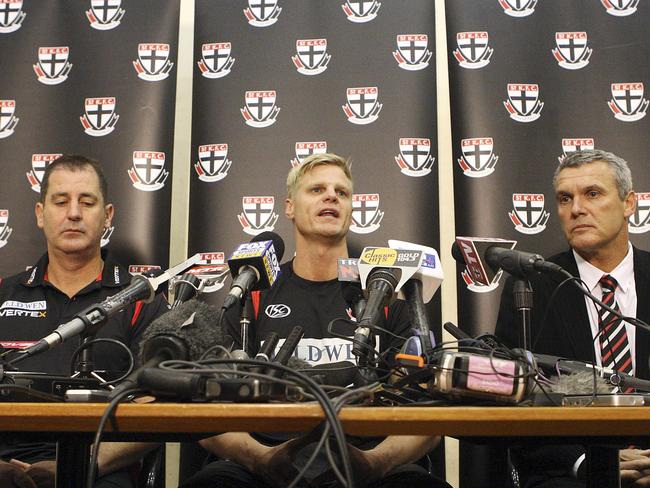

NUDE PICS, LIES AND RICKY NIXON

WHEN you’re on the other side of the world with a group of mates after months and months of leading an incredibly disciplined lifestyle, you tend to let your hair down.

Details can become a bit fuzzy. Some might say that’s convenient. It’s just the truth. Ultimately, all that happened was, in a room full of blokes, one man (Sam Gilbert) took a photo on his phone of another man (me). That’s it. I imagine it just seemed like a funny thing to do at the time. It was just so inconsequential at the time that the photos were taken.

It certainly wasn’t a big moment of, ‘Ooh, we shouldn’t have been taking these photos ...’

It was just a non-event. I had no inkling of what was about to happen.

In the gym at Moorabbin on the last day of pre-season training before the Christmas break one of the boys came out of the physio room, which was next door, and said, ‘Come and have a look at this — quick.’ I walked into the room and found a group of my teammates sitting around a computer looking at an image of me, naked, with Zac Dawson next to me. It was captioned, ‘Merry Christmas from the St Kilda Schoolgirl’. The girl had posted the photo on Facebook. Holy shit.

The photo scandal had just exploded. I was absolutely devastated, knowing straight away what it would mean to my reputation. That’s something that means a lot to me: I’d maintained a clean image throughout my career, which is essentially the person I am. I’m pretty straight.

To be dragged into something like that was humiliating and absolutely beyond my control.

It’s not as though I was naked in a photo with another girl, or engaging in something I shouldn’t have been, cheating on my partner, doing drugs, or whatever. I was just standing there, naked. Big deal.

I was just standing there, naked. Big deal.

There are two other moments in the whole saga where I wish I could have my time over.

The first came out of that lawyer’s office meeting the day the photo of me and the one of Dal were posted on Facebook. I said we needed to get on the front foot, that telling the truth would diffuse the whole thing. All it did was make me the poster boy, and intensify the spotlight on it. I thought people would think, ‘He’s been caught up in something here that wasn’t of his doing, he’s a respected player, he’s had ten years in the game without anything untoward, we’ll let this go.’ That’s how I was hoping it would be received. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

My other mistake was trusting Ricky to fix the mess. I started to smell a rat when Ricky called me and said, ‘You’re not gunna believe what they’re saying now. They reckon I’m involved with her’. Then the photo of him on a bed in his undies came out. Ricky was still really strong in his denial, but he started to become evasive, went to ground. It turned really quickly when incriminating footage emerged. It was obviously Ricky and he had nowhere to hide. I went into self-preservation mode because I had a bit of money tied up in his management company, Flying Start.

I got in touch with the woman who did the books and she said, ‘Oh Nick, I’m sorry, there’s no money, it’s all gone.’ Ricky owed me a lot of money. I severed ties with him straight away.

Ricky was amazing for me as my manager. A good friend who opened a lot of doors. He was incredibly good at his job — until he wasn’t.

The effect the whole saga had on me was profound. I was called a liar in the media by people who refused to believe the circumstances of the photo were innocent. People made what they wanted of it. That’s a horrible thing to have to carry.

THE DAY EDDIE WANTED ME AT COLLINGWOOD

During grand final week of 2013 Eddie McGuire invited me over to his house to talk about my future, essentially (at least to my thinking) where I saw myself going in the media.

I’d done The Footy Show sporadically for a long time, and with the Saints finishing way short of the finals I was spending that September doing special comments for Channel Seven.

MORE ON NICK RIEWOLDT:

RIEWOLDT SAYS NAKED PHOTO SCANDAL WON’T FRACTURE CLUB

ROBBO: RIEWOLDT AN EMOTIONAL, MATCH-WINNING, GREAT OF THE GAME

JON RALPH: THE DAY HARVEY THOUGHT HE KILLED RIEWOLDT

Working in the media post-footy is an avenue I’d thought about pursuing for a long time, and there are few better people to have that conversation with than Eddie.

I lobbed at his house in Toorak, and it was just me and him. We opened a beer and Eddie said, “Look, I want to talk about you coming to Collingwood.” Just bang, straight out with it. Gosh, Eddie’s good. I can’t believe Collingwood people when they bag him.

To have someone in your corner like Eddie McGuire, who likes nothing more than getting out and slamming the desk for your club, is pretty special.

So Eddie played his hand. “You’ve done the right thing by St Kilda, they’ve already said you’re going down a path of rebuilding. Goddard’s left, Dal Santo’s leaving, Montagna’s talking to clubs.”

He knew things weren’t great at the club and he was right; a couple of weeks later Scott Watters was sacked as coach. Lenny, Milney, Kosi and Blakey (Jason Blake) had all finished up. Throw in the names Eddie was using as bait and there was a chance all of the old guard would be gone except me. We had a conversation, which was largely Eddie selling what Collingwood had to offer.

“Instead of playing in front of 20,000 on a Sunday afternoon at Etihad you’ll be playing in front of 100,000 on Anzac Day at the ’G, that sort of stuff. Almost as a sweetener he threw in that, with Emirates as the club’s major sponsor, Cath and I would virtually have our own personal travel agent at our disposal for those annual trips to the States. Never mind that Emirates don’t even fly direct to the States, it was part of the sell. Cath was already in Houston, and a few days later I got on a plane to join her. It was the day after the grand final. I’d worked with Seven on the coverage the day before, seen Hawthorn beat Fremantle for the first of its hat-trick of premierships, and I was glad to be getting out of there.

‘You’re always going to have money. The difference isn’t life-changing money, but the decision to leave is.’

We were sitting on the runway waiting for clearance to take off, I had a champagne in front of me, and my phone buzzed with a text message. It was Eddie. ‘Hey mate, before you take off ...’ It was almost spooky — I had to sneak a look over my shoulder to check he wasn’t on the plane! ‘Before you take off, I just want to leave you with two words: Brian Lake.’

The message went on about how Lake had left the Bulldogs, a similar club to St Kilda on a similar downward trajectory, and the very next year he’d played in a flag and won the Norm Smith Medal. ‘This is what you deserve,’ Eddie’s text said. He’s so good; he knew I was going to be on a plane for the next fourteen hours, and that was all I’d be thinking about. It was an incredible sell. I didn’t even know if he’d spoken to Collingwood’s recruiting boss Derek Hine or more importantly coach Nathan Buckley — I presume he had. He was talking three years, on decent money for a soon-to-be 31-year-old. In thirteen years at St Kilda I hadn’t come close to leaving. There had been discussions between my then-manager Ricky Nixon ahead of Gold Coast coming into the competition. I heard some figures —$1 million-plus a year over five, which would have been the biggest contract ever signed in the AFL — but I never saw a formal offer.

Staying at St Kilda was a pretty easy decision. It was eight or nine games into the 2009 season, we were undefeated, and it looked like we were on the path to having sustained success.

Mum, Dad and Maddie had moved down to Melbourne at the start of 2009, which would have made for an ironic turn of events if I’d packed up and headed the other way. In the short time I was mulling over a move, Mum and Dad gave me some terrific advice: ‘You’re always going to have money. The difference isn’t life-changing money, but the decision to leave is.’

It hit home that big decisions should be made first and foremost on the direction they’ll take your life, not on what they’ll inject into your bank account. So now Collingwood — or at least its president — was making a play and I had to consider another big move, against a backdrop of a team that was seemingly going in the opposite direction to the one I was leading when Gold Coast came knocking. Once I got to the States I spoke to Tom Petroro, who looks after my contractual stuff, and then with the club. I told them the Magpies were keen, said I was thinking about it, and asked what was going on with Joey, who had been in talks with Essendon. The waters became even more muddied when Scott was sacked and, in reply to a voicemail I’d left him, he sent me a text that essentially said the club wouldn’t think twice about doing the same to me.

If Joey had left, who knows what I would have done. But I stayed, played another five seasons, and finished as that person Cath’s mother Caroline liked before she’d even met me: a one-club player. And I’ll always be incredibly proud of having been a Saint my entire football life, proud that when my kids grow up there’s only one place I’ll ever take them. I’m drawn to St Kilda for all its warts, its eccentricities, its rich history and the bits that haven’t been nearly as glittering. I’m a St Kilda person. And I love that I’ll always be able to say that.

THE HARDEST TIME OF MY LIFE

MADDIE went into ICU in July, and stayed there for 227 days. Over the five years of her illness she spent roughly eighteen months in hospital, but nothing could prepare you for those last seven months. Maddie spent five of those seven months unable to eat or drink, on and off dialysis, and using a tracheostomy, which creates an airway through the neck to deliver more oxygen to the lungs. Sometimes we were allowed to take her out on the balcony; my memory is stuck in the last few months, when it seemed like every time we were out there it was a really hot day.

The hardest thing about that time, which still breaks my heart, is how thirsty Maddie was.

She was basically thirsty for six months. Occasionally she would be allowed to suck on an ice chip, then the nurses would say no more. Maddie’s eyes would just sink.

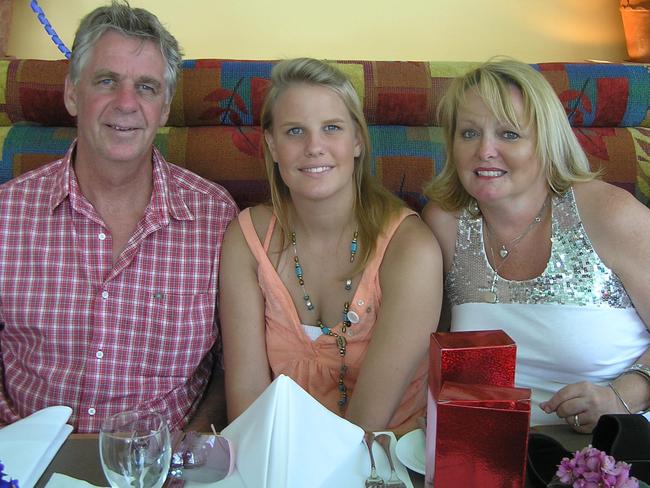

You question so much in a situation like that. If you’re going to lose someone, how would you prefer it to happen? Would you rather lose them suddenly? Or would it be better to have time to prepare yourself, but have to watch the deterioration of someone you love? To say we admired her courage is such a ridiculous understatement. I can’t articulate how strong she was and how proud of her we are. She became a shell of herself. She was unrecognisable from the beautiful blonde girl she’d been, but at the same time she was still our Maddie.

To say we admired her courage is such a ridiculous understatement.

James had been born on 4 December 2014. By Christmas it didn’t look like he would ever meet his Aunty Maddie. Then in January, with a new course of medication seemingly reaping results I got a phone call to say she was no longer infectious. I was so excited, I just grabbed James and Cath and raced in there. Maddie couldn’t talk, but I could still hear her over the ventilator — which you’re not supposed to be able to do — saying, ‘I love you James, I love you James.’ That’s one of my favourite memories, hearing her say my son’s name, telling him that she loved him. For a sliver of time, after so much darkness, everyone was happy.

Maddie’s improvement continued through January, by February Maddie was in the best state she’d been in for a long time. Then, within the space of days, she contracted a critical infection.

At the hospital they gave us the worst news possible. “We’ve done everything we can. She’s too sick. She’s not coming home.” I was angry. They’d never said anything like that before. It was denial, I can see that now.

We were told nothing would happen straight away and were sent home, and at 5am the next morning Dad rang and said, ‘Mate, you’ve gotta come in.’ It was such a strange feeling, knowing the inevitability of what was about to happen.

We sat by the bed asking questions of the hospital staff: Is she in pain? Can we wake her up to say goodbye? That wouldn’t have been fair on Maddie — she had been in a coma and would have been so disoriented; I’m sure she would have been scared. But how do you say goodbye to your daughter, to your sister, to someone you love? I rang Cath and asked her to bring James in. I wanted him to be there, sitting on Maddie’s lap. We all gathered around Maddie as they turned down the machines and removed some of the things that had been keeping her alive. I was holding her hand. We were all touching her. James’s little hand was wrapped around Maddie’s finger. And then she was gone.

I’m sure your mind protects you to some degree from going somewhere painful. It’s strange the triggers that bring Maddie back. When I was still playing, I could be driving to training and take a drink out of my water bottle, and that terrible time when Maddie wasn’t able to drink would just pop into my head. Then I’d see how long I could go without having a drink.

I knew it was stupid, that it would just make me sad all over again, but I’d do it anyway.

For a long time I couldn’t listen to a song with the word ‘she’ or ‘her’ in the lyrics.

The word ‘sibling’ took on a new meaning. I would do school visits with the club, and when it came to question time invariably some innocent kid would ask if I had brothers or sisters.

The first few times I just froze. I learnt to say, ‘I’ve got a brother and a sister, but unfortunately my sister passed away.’ If I saw a scene in a movie or a TV show with a hospital, or someone who had been shot and was dying in someone’s arms, I’d go straight back to the Royal Melbourne ICU.

Anyone who has held someone’s hand, been with someone when they have taken their last breath — I’m sure they’ve gone through the same sort of emotions. Even little things like watching the news and seeing a story about a twenty-something who had stolen a car or done something stupid, I’d just think, ‘F--- you. Maddie should still be here and you shouldn’t.’

The good memories have slowly become easier to locate.

Losing Maddie has heightened something that’s always been part of who I am — anxiety.

I’m not depressed but I’ve definitely known anxiety — particularly separation anxiety — and it’s wrapped me up all the more in the years we’ve been left without Maddie.

After Maddie passed away I started having anxiety attacks. I could be in the shower, or driving the car, and it would come over me. I have never passed out during an attack and, if I just sit quietly, put my head in my hands and compose myself, it will eventually pass.

These anxiety attacks were happening roughly once a month, then around the time of the second anniversary of Maddie’s passing, in February 2017, they became more severe.

That day I had five separate anxiety attacks: in the car on the way to the footy club, in the warm-up, during a running session, in the change rooms, then on the plane later that day.

The frequency forced me to do something about it and I started speaking to a couple of people — it was diagnosed as post-traumatic stress.

That day I had five separate anxiety attacks: in the car on the way to the footy club, in the warm-up, during a running session, in the change rooms, then on the plane later that day.

Talking about it helps. I’ve worked at the moments where I’m out and about and become anxious, where the feeling that I need to pick up the phone and check in becomes overwhelming. I’ve worked at not doing it, at not becoming reliant on that, and I’ve become better.

If anxiety is part of that journey to understanding, then so be it. If the upside is feeling a deeper connection to Mooch, I’ll wear that.

Feelings are what we’re left with, and as much as the good memories fight their way to the surface of your mind as time passes, the overwhelming feeling is hollowness. It is deeper than sadness, more than just an emptiness at not being able to hang out with her and see her grow old. None of us are the same. Everything we thought we knew when Maddie was in our lives, we’ve lost. But together, we’re learning to live with what has become our new normal.

From The Things That Make Us by Nick Riewoldt with Peter Hanlon, published on 23 October 2017 by Allen & Unwin.

Be one of the first to buy The Things That Make Us for $34.99, and receive a copy signed by Nick Riewoldt. Order online at heraldsun.com.au/shop or call 1300 306 107 from 10am Monday.