Royal Children’s Hospital Appeal: Brave William arrives home after heart transplant

HALF a year ago William lay on a hospital bed in a silence that choked his parents’ hearts. But miracle surgery has delivered his only chance at survival.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT WAS the silence that choked their heart. William Mitchell has not long found his voice.

The 17-month-old started that day like any other, snuggled between his parents in bed enjoying a bottle of milk as he babbled away in his own language.

But now there he was on the hospital bed and silent. Tubes, lines and probes attached to every limb.

The beeping of machines, the hum of the lung-bypass pump and the hushed voices of intensive care staff were the only sounds to cut the silence for Julia Davies and Tristan Mitchell.

Their baby boy’s heart was failing.

Machines were keeping him alive.

It is exaggerated to say this scenario is a parent’s worst nightmare, because what parent would ever let this scene enter their mind?

News like this evokes stunned shock. But William was so active, so curious, so healthy. How could this be possible?

The toddler had been “a bit off” for a couple of weeks with gastro-like symptoms.

At 6.30pm on that Sunday in late August, his parents took him to the Royal Children’s Hospital emergency department, not satisfied with the GPs assessment earlier that day that William was fighting a virus.

He was still vomiting and his breathing was “grunty”, but now his lips were now tinged blue. By 10pm he was in intensive care.

At midnight they were told his heart — the linchpin of life — could not sustain beating overtime at 205 beats per minute.

He was placed on ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation), a heart-lung bypass machine reserved for the most critically ill patients in the hospital.

But after five days on life support it was clear to doctors that William’s heart would not recover on its own.

His only chance at survival was a new heart. They would not be able to leave the hospital until they got one.

The cruel reality of organ transplantion is that hoping for life means waiting for death.

“We were walking around in disbelief for the first few months,” Ms Davies said.

“All we could say was; ‘How did we get here? How did this happen?’

“We don’t ever go; Why us? Because why not us. But how? It was like being stuck in a bad dream.”

They will most likely never know what caused Williams’ heart to shut down.

The couple can look back at photos and see the puffiness under his eyes in those preceding months.

They can see now how pale he looked.

Julia can pinpoint the time where he stopped growing.

A Berlin heart, a Ventricular Assist Device that sits outside the body and takes over the function of the organ, would keep him alive until a suitable donor heart became available.

William was the second child in Australia on a Berlin Heart at that time.

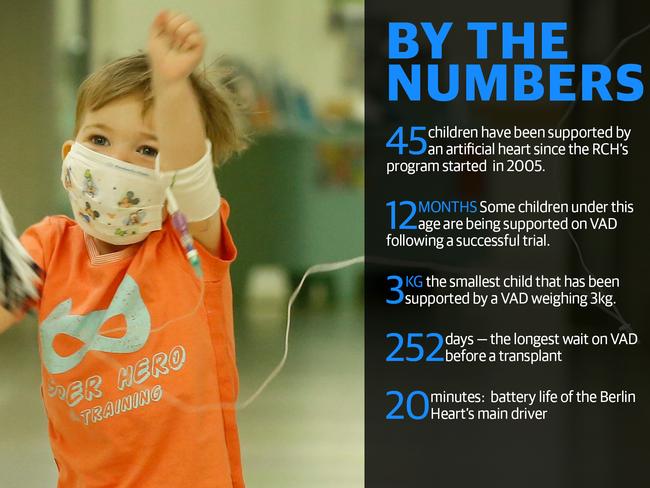

Soon there were six others on the cardiac wards joining him; the most number of children ever supported by VAD at any one time at the RCH.

And while the RCH, as the National Paediatric Heart Transplant Centre, has made significant breakthroughs in recent years including using circulatory support on newborn babies, this bridge to transplant is not without its risks.

There is a 30 per cent chance that VAD will cause a stroke or infection that could render them ineligible for a transplant.

Cardiologist Dr Lucas Eastaugh, who co-leads the VAD program at the RCH, said they warned all families from the start that doctors would never discuss where children are on the organ donor waiting list.

There had not been a heart transplant for more than four months when William joined the waiting list.

But being first on the list doesn’t guarantee you get the next heart.

Organ donation is a complex matching exercise that considers how stable a child is, their blood group, whether it’s a tissue match, age and how long they’ve been waiting.

“It’s human nature to wonder where is your child on the list,” he said.

The odds for a timely transplant are getting better for young children like William.

The RCH team is now doing double the number of transplants — now an average of one a month — compared to just a couple of years ago.

Cardiologist Associate Professor Robert Weintraub, who leads the heart transplant team, said they had been casting the net wider to identify suitable donors.

Many children under 12 months of age can now accept a heart from a different blood group, following the hospital’s work as their immature immune systems more readily accept them.

They now used oversize donors, as big as it can fit into the child’s chest, as well as slightly undersized hearts with success.

“We do everything we can to make sure we don’t turn down any suitable donors, but we still can’t make donors happen is there are no suitable ones available,” he said.

“Australia’s donor rate still lags well below that of Europe and North America.”

As the Berlin Heart took over the function, William’s condition stabilised and he learnt to walk and talk again after his paralysis following a stroke in intensive care.

Making full use of the 20 minutes battery life of the artificial heart’s driver, William would run and play in the sunshine — to the disbelief of doctors who marvelled at his energy — as his parents wheeled the 160kg device and accompanying trolley of oxygen bottles behind him.

The RCH team is now doing double the number of transplants — now an average of one a month — compared to just a couple of years ago.

Cardiologist Associate Professor Robert Weintraub, who leads the heart transplant team, said they had become “more aggressive” in casting the net wider to identify suitable donors.

Many children under 12 months of age can now accept a heart from a different blood group, following the hospital’s work as their immature immune systems more readily accept them. They now used oversize donors, as big as it can fit into the child’s chest, as well as slightly undersized hearts with success.

“We do everything we can to make sure we don’t turn down any suitable donors, but we still can’t make donors happen is there are no suitable ones available.

“Australia’s donor rate still lags well below that of Europe and North America.” As the Berlin Heart took over the function, William’s condition stabilised and he learnt to walk and talk again after his paralysis following a stroke in intensive care.

Making full use of the 20 minutes battery life of the artificial heart’s driver, William would run and play in the sunshine- to the disbelief of doctors who marvelled at his energy — as his parents wheeled the 160kg device and accompanying trolley of oxygen bottles behind him.

But the waiting continued.

Days were spent largely confined to his room, watching for trams and dogs and bikes in the parkland surrounding the hospital.

The longer they waited, the more anxious Julia and Tristan became. They could see the Berlin heart working, they could see the blood filling the pump that hung below William’s T-shirt like an udder, and could see the strong kick it received with each pump.

“I’d look at him and think what are we doing this for, because it’s never going to happen,” Julia said.

“We hadn’t seen any transplants for four and a half months.

“At the start we expected to be in for the long haul, but as the months wore on we became extremely disillusioned. I lost hope.”

But his day did come.

Typically patients are discharged from hospital about two weeks after receiving a new heart. But William has spent the past 10 weeks battling recurrent infections, including two stints in intensive care from kidney dysfunction, and treatment for a virus.

But this miracle isn’t a cure.

Donated organs have a shelf life.

It is likely that at some point in the future he will need a new heart.

But after returning home following 187 days in hospital, and no longer being attached to a 160kg machine for circulatory support or an IV pole, the young family are relishing the chance of the simple family joys like a walk to the park and trip to the zoo.

“We are so lucky that we live in the era where modern medicine is advancing, and we’ve got our son now,” Ms Davies said.

“We don’t know how much time we have with him. “It’s given him life, but we’ll always have his ups and downs.

“The fact that we’re celebrating a second birthday is amazing. Six months ago we never thought that’s what we would be doing.”