Released from jail with no money, home or mates; this ex ice addict and dealer fought his way back

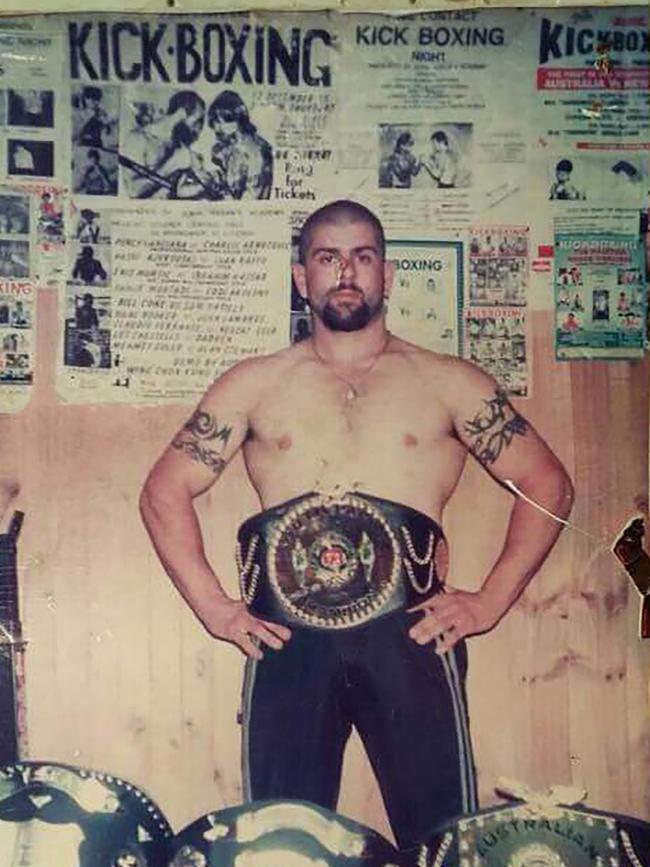

Former kickboxing champ Simon Fenech was a husband and dad with a nice house and good job when he first tried ice. This is his journey to hell and back.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Simon Fenech was the Australian kickboxing champion. He had a wife, young children, a house and a solid job. Then, through a series of poor choices, he became an ice addict, drug dealer, was jailed, and tried to take his own life. He spoke about making poor choices, fighting his way back, and the need for people to be given a second chance.

HM: Kickboxer, father, drug user, drug dealer, jailbird, author and Fruit2Work director and manager. It’s been some sort of a life!

SF: Very much so. It’s not how I thought my life would go!

HM: You grew up on the farm, with a loving father – you were very close to him. Everything was going well until he passed away. Is that when your life took a huge turn?

SF: Most definitely. That was the start of my downward spiral. Once Dad became sick, I watched cancer eat him away. When he died, I lost my way and started going backwards.

HM: In what way?

SF: Dad was as fit as a fiddle, and all he did was commit to his family. He never drank, never smoked, never gambled. When I saw him die at 60, I thought, ‘there’s got to be more to life than working and paying off your house’. I was popular because of the kickboxing, so I started bouncing at nightclubs and getting into the dark side of things.

HM: Was that the beginning of the end?

SF: No, I was able to pull myself away, I got away from the murky stuff. I knew I was headed off course, so I got a normal job on good money. My life was going well, but then I was injured at work.

HM: You were an Australian kickboxing champion, gained popularity and notoriety. The attention went to your head, you started bouncing and got into the wrong lifestyle with the wrong crowd.

SF: My priority shifted. I started bouncing in a strip club in Geelong, and I thought it was my duty to protect the patrons of the club. I started staying out all night, getting

to know anyone and everyone in Geelong. That was when I started to mix it with some of the heavy hitters.

HM: How old were you at that point?

SF: About 27.

HM: You said your father was a hardworking Maltese labourer who died with very little. You felt he should have had more to show for years of toil?

SF: That’s exactly right. I decided I wasn’t going to just work and work and work and have nothing to show for it. I had missed out on the travel, the nightclubs, the camping and all of that because of the kickboxing. I was married at the age of 19, working two jobs, and paying off a house. That was bred in me. I chose to leave my wife; I still supported my kids. I met another woman, and it wasn’t long until I was hitched with her. I bought a double-storey house, I was driving a Mercedes and a Harley-Davidson. Everything I’d touched had turned to gold, until one day a workplace accident happened.

HM: Had you paid for the house and cars and bikes with honest money?

SF: I did.

HM: Then you’re worked for one of the country’s leading supermarket chains, making good money, and you were struck in the back with a forklift. The lower discs in your back were crushed, and suddenly you were in a wheelchair in enormous pain.

SF: Correct.

HM: You’d tried everything to ease the pain, but nothing had worked. One day out of the blue, a friend of yours came around with marijuana.

SF: That’s right.

HM: Had you tried drugs before?

SF: Not really. Because I was training, it was never an issue. I tried ecstasy once, speed twice, I even tried marijuana, but that was it.

HM: No addiction?

SF: No addiction at all. Never had a drop of alcohol or smoked a cigarette – nothing.

HM: He came around with the marijuana, you didn’t like it, so he disappeared. A few days later he came back with ice, and that was the beginning of the end.

SF: Yes, it was. Ice is a drug that I had never experienced before. It numbed my back pain.

HM: And you end up throwing the doctor’s medications in the bin, and you thought self-medication on ice daily was the way forward?

SF: I thought I knew better than the doctors. How stupid I was.

HM: Ice addiction becomes expensive, doesn’t it?

SF: It does. The first time I tried ice I tried $50 worth. That kept me awake and feeling fantastic for two days and two nights. The second time I tried it, it kept me awake for two days and two nights, but there wasn’t that fantastic euphoric feeling again. You always chase that feeling, and before you know it, you go from $50 to $100, $200, $300, and at times, between $1000 and $1300 a day.

HM: Not many can afford that.

SF: And I was one of those people that couldn’t. In the drug world, you deal to cover your habit, you steal. I wasn’t much of a good thief, but I was always good with numbers. I thought I would take on dealing drugs. Under the influence of any narcotic, you don’t make any good decisions. I had no idea what I was leading myself into. It became a lifestyle. You completely change the people that you hang around. I had good hardworking friends, and I had pushed all of them away. The only people I surrounded myself with were other drug addicts, other ice users.

HM: Who do you call to start buying two, three, four, five, 10 grams of ice?

SF: At that time, there weren’t a lot of options. It took me three to six months to find out who was who in the zoo. You work yourself up in the chain. I wasn’t a kingpin in the drug world, I was just the tip of the iceberg, there were huge players beneath me that are rarely seen. Everybody that I knew dealt in their own way. I was halfway up the chain, but nothing compared to a lot of the people out there. I dealt to cover my habit, and the more I dealt, the bigger my habit became, because the drugs were more available, and cheaper. It’s an ugly world.

HM: Am I right in saying the seller of the drugs to the user has no idea where the drugs come from or what’s in them, and there’s a chance the person that the seller bought it off has no idea? But what you know unequivocally is it’s unbelievably risky to put it into your system.

SF: A lot of people I know have gone on about this Covid vaccine, worried about putting that in their system. Some of the things I have experienced in the ice world, the vaccine certainly wasn’t a threat for me.

HM: I assume it’s a world full of lies, deceit, deception, theft, corruption, drugs and guns?

SF: It is a deep, dark, dirty and putrid world.

HM: When you were dealing, you were shot and stabbed?

SF: That’s correct. I was shot in the thigh. While we were fighting, one of them pulled a 12-inch kitchen blade out of his sleeve and stabbed me three times in the back of the neck.

HM: What were you fighting over?

SF: These guys knew that I had drugs, they also knew I had money, and they tried to stand over me. Another underworld tactic. They wanted my drugs and cash, and didn’t mind killing me for either.

HM: You were selling a lot of drugs, which means you had a lot of cash. You can’t go and put it in the bank, can you?

SF: There was never a shitload of cash really, or a big heap of drugs. You only go from deal to deal basically. When I say I sold a lot of drugs, it was a lot, but small amounts. It wasn’t kilos, it wasn’t half kilos, it was only grams at a time. It has a currency.

HM: How do you end up in jail?

SF: Once I hurt my back and I started using drugs, I was bored out of my brain. I was up all night, I was buying cars and selling them, and before I knew it, the council was on my back. I shifted into a small factory and started up a small wrecking yard, where I’d buy a car, strip it, and sell the parts. I started dealing out of that factory, and numerous times I was raided by the police. I was running a 24-hour operation, and nobody slept, everybody that worked with me were on the drugs. I was dealing out of there. I was raided three or four times, and each time I was raided, the cops found drugs. That led me to jail. While I was using drugs, I lost my brother, three months later I lost my mother to dementia, and then 12 months after I lost my baby daughter.

HM: How old was your daughter when she died?

SF: Nine days old. In a life where there was no light left, she would have brought that, she was going to be the boost that I needed to clean myself up.

HM: You buried her, and then you tried to take your own life multiple times after that?

SF: Five suicide attempts.

HM: Can you articulate now why you tried to end your life?

SF: After losing my family, surrounding myself with shit people, and not being able to trust anyone in the world, in my eyes, I was better off dead. I still had three kids, and I was ashamed to be their father. I thought they were better off without me. It was a dark time; I just didn’t want to be here. That was how I felt for a long period of time. I tried to get help, I’d see counsellors even when I was on bail, and they were worried about how they were going to get paid. It was a time when I thought my life was worthless, and it was all because I headed down the path of drugs.

HM: How long were you sentenced to jail for?

SF: First they put you in on remand, until all your court cases and the police gather enough evidence. I was on remand for five months, not having any idea what I was facing. After five months, and three or four different court cases, the judge was very empathetic. In the five months that I was jailed, I was able to clean myself up, I didn’t use any drugs, or any of the doctors’ drugs in jail.

HM: How easy is it to get drugs in jail?

SF: Very easy.

HM: When you first got to jail, were you still using? Were you still an addict?

SF: Yes, I was.

HM: At what point, and how, do you stop your use, remove the addiction, and start turning your life around?

SF: That was easy for me. When you are locked up in a three metre room, and your cell mate is taking a dump while you are eating your dinner, you can’t get much lower than that. You are sleeping on a three-inch foam mattress, on a concrete base. You are locked in the cell from 3.30pm, for the rest of the night. You don’t have access to the drugs at your fingertips, or the money. That’s when I said, ‘I’m not doing this any more. I want to get my life back. I have to get my life back’. After three, four, five months, those chemicals in your brain start to recreate, and you start to think rationally. You start to feel better, you start to feel like a human, but then you’ve got to work out what you’re missing, what you’ve missed, and what you need to succeed in life on the outside. That’s when I popped my head into every program, every course, and used every possible tool I could to better my life once I was released from prison.

HM: Once you decided enough was enough, was it difficult for you to stop using ice? Were there relapses?

SF: I couldn’t think of anything worse than being on ice in prison. You don’t want your mind going a million miles an hour when you’re stuck in a cell. Not to mention, if you got caught, you’d lose any benefits like visit privileges, phone privileges, your life would be even worse.

HM: When you were released, and you stepped outside, how do you then go into a clean world, job wise, and a clean world living wise?

SF: With a lot of difficulty. When I was released, I had nowhere to live. They sent me to a boarding house.

HM: Were you still married at the time?

SF: The marriage had ended, my ex-wife and the kids didn’t want to have a bar of me because I was a drug addict, and they were right to do that. The only support I had was my brother, one brother, who is the only member left of my family. He’s a Justice of the Peace. He went one way in his life, and I went the complete opposite. He made it very clear that he would support and help me wherever he could but he also created boundaries. I couldn’t live with him and I had to do some things for myself.

HM: Where did you go first, given you had no money and no family willing to have you?

SF: They released me into a boarding house, and the boarding house was infested with drug addicts. The lady who answered the door was off her face on heroin. My room had three syringes on the carpet, and there was a huge blood stain in the middle of the mattress. That’s where I was released to, and that’s where I had to start my new life, in a putrid boarding house. I begged my brother for help, so he put me up in a hotel for a few nights and got me into a drug free boarding house. That was the start of a second life for me.

HM: And then you needed a job.

SF: I wasn’t released a free man. I still had a corrections order for 18 months that I had to get through. I had to do 380 hours of community work, I had to do a drug and alcohol program, I had to do a men’s behaviour program, I had to do a mental health program, as well as see a case manager once a week. Try and do all those things and get a job at the same time - nobody wants to know you.

HM: What was the general response from potential employers?

SF: There was no reply. That’s just the corrections order, not including the criminal record. Who wants to employ an ex-junkie, thief, and drug dealer? Who wants to give somebody like that a second chance?

HM: Is that why you believe most offenders reoffend and end up back inside?

SF: 120 per cent. When you come out of jail, you need three things. A friend, a job, and a roof over your head. The friend, not so bad, but the roof and the job fall hand-in-hand. If you are sleeping in an alleyway, you’re not going to get a job. If you haven’t got a job, you can’t afford to put a roof over your head. In Victoria, 47 per cent of people that have come out of a jail, go back to jail within the first two years. All we do is keep locking them out.

HM: You need a big break to re-enter society?

SF: You do. I applied for job after job, with no luck. I ended up going to see my caseworker at corrections and said, ‘I don’t know what else to do. I am seriously considering going back to doing what I used to do’. I knew this time I would end up in jail for a very long time, or dead. By fluke, the company that I am the general manager of today put a flyer out, asking for offenders who had been released from jail to come and work. I applied for the job. It was only two days a week, but it was a door that opened. It was the start. That job changed my life. For somebody to give me that chance, for me to go home in a high vis uniform and pay tax, and be able to buy my kids presents, and show my kids that I had a job and was doing the right thing - I just grew, and grew, and grew from there.

HM: How many of Fruit2Work’s employees have ended up back inside?

SF: Not one. I was released from prison in 2016, when Fruit2Work was six-months-old. Since then, we have transitioned 63 people back into society, into full time work, and not one person that has come through the program has gone back to prison. You start at 3.30am. You are delivering fruit and milk in the early hours, but we give them the skills they need, we help them set goals, we work within their parole requirements, and once we think they’re ready, we transition them into full time employment elsewhere and bring more people through. It’s a not-for-profit social enterprise, and every dollar the business makes goes back into creating more chances for people like me.

HM: You have a life again because you were given a second chance.

SF: Today I have a beautiful fiance, we have bought a block of land, we are going to build a house, I have my family back, my kids are back in my life, I have custody of my youngest son, and life is as good as I could possibly imagine.

Simon has written Breaking Good, available online and in selected bookstores.