Peter Norman remembered for his role in the black power salute with Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics

IT is one of the most famous photos in the history of world sport. Half a century on, the actions of a 178cm son of devout Salvation Army parents, born and bred in Coburg, which shocked the world, remain as significant as ever.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THAT John Carlos and Peter Norman will forever be linked as Olympic brothers in arms is all the more remarkable given their initial bond was far from evident 50 years ago in the Mexico City village.

Carlos was born to Cuban parents in the New York City neighbourhood of Harlem and would grow into an angry 193cm sprinting sensation, as fast with his tongue off the track as he was on it with his flying legs.

By the time the 1968 Olympics had arrived, Carlos was ready to make a statement.

PERMANENT MEMORIAL FOR PETER NORMAN

THE SPORTS STARS THAT MADE POLITICAL STATEMENTS

WHY YOU’VE NEVER HEARD OF OUR MODERN DAY NED KELLY

He went to those Games supremely confident he would fight out the 200m gold medal with teammate and world record-holder Tommie Smith, who was the more quietly spoken of the pair.

But Carlos wanted more than a medal, having witnessed his black countrymen suffer for too long and realising that all going well, he would shortly have a world stage on which to protest.

Then there was Peter Norman, a 178cm son of devout Salvation Army parents, born and bred in Coburg, many miles removed from the unemployment and high crime rates that Carlos had grown up with in Harlem.

Prior to the ’68 Games, the pair had never met, even though Norman was acquainted with Smith through athletic meets in Tokyo and Melbourne.

Smith was approachable, so when he and Norman bumped into each other in the Olympic Village a few weeks prior to the 200m heats, they chatted easily. At least until Carlos walked by.

“Hey, who’s the white boy?” Carlos asked Smith, outraged that he was talking to their Australian rival. The account is published in an illuminating book, The Peter Norman Story, out this month.

“So Tommie introduced me to John, who then made some derogatory remark about where he was going to kick me. John was mean and nasty and more of a junkyard dog,” Norman said.

A junkyard dog indeed, as he revealed in a pre-race interview with Australian journalist Jim Webster.

“If you want to see how we are going to demonstrate, stick around fella. We are determined to draw attention to the unfair treatment given to black Americans,” Carlos told him.

“All you press, radio and television people chase after me when I’m on the track, but not after it. I’m just a n----- then and you wouldn’t want to know me.”

Three weeks later, Carlos still had the anger, but standing alongside him on the most famous Olympic medal presentation of all was gold medallist Smith and a white man named Norman who had shocked the world by running past Carlos late to claim silver.

The events of that 200m event have helped shaped history, due to the bravery of two black US athletes and a 26-year-old Australian who decided on the spot he was going to be a rebel for a cause.

Norman sadly died in 2006, prompting the US Track and Field Federation to name the date of his funeral, October 9, “Peter Norman Day”, a tradition that still exists today.

On Tuesday the Victorian government is set to make an announcement concerning the 50-year celebration of Norman’s run and later actions. You could ask why it took us 12 years to catch up with the US in recognising a man who stood up for a cause he passionately believed in.

Sadly, that has been our way at times in athletics in this country, attitudes that angered Norman and progressive-thinking champions such as Raelene Boyle and Ron Clarke.

There is even talk of a movie today with interest from Hollywood, and thankfully Carlos and Smith are both still alive to recall their stories.

HOW NORMAN HELPED SHAKE THE WORLD

OCTOBER 15 (DAYTIME) 1968:

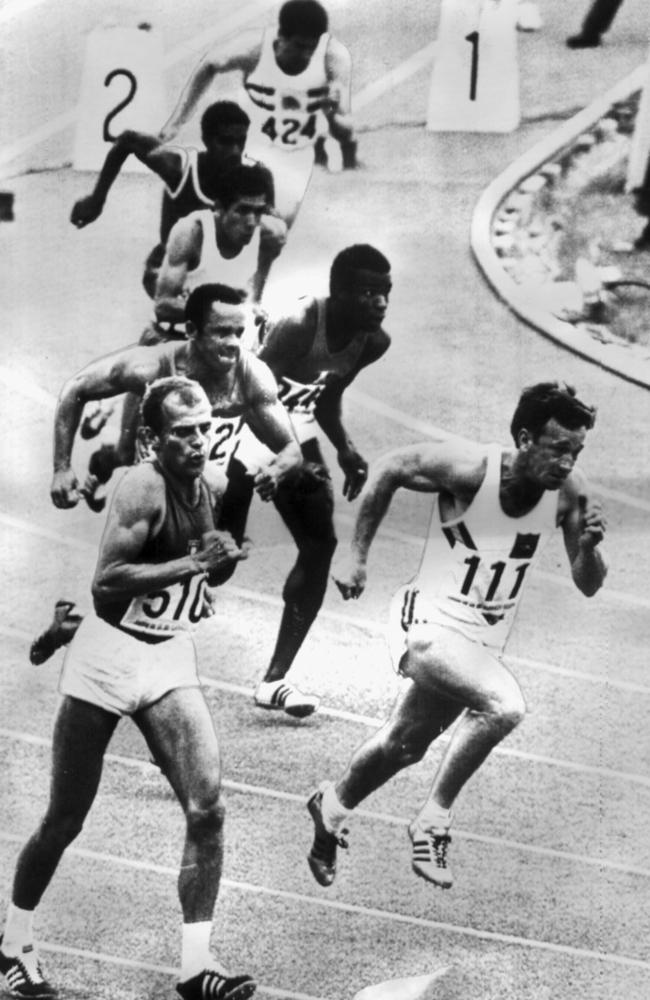

Norman is one of two Australian runners competing in the 200m (Greg Lewis is the other) at the first Games to use an all-weather (smooth) track, rather than the traditional cinders.

For Norman, the surface is akin to Rafael Nadal discovering that all four tennis majors are to be played on clay.

His legs seemed to bounce off the track, his times steadily improving in the build-up. By the time the heats and quarter-finals arrive, Norman has started to signal his arrival on the world stage.

He confirms that with a blistering 20.17sec in heat 6, equalling the Olympic record.

Later in the day Norman wins his quarter-final (as do Carlos and Smith) before returning to the Olympic Village, content in the knowledge he is a genuine chance to join Stanley Rowley (1900, bronze medal, Paris Olympics) as the only Australian male to win a medal in the 200m.

OCTOBER 15 (EVENING) 1968:

Norman is introduced to the great Jesse Owens, who 32 years earlier had gone to the 1936 Berlin Olympics and destroyed Adolf Hitler’s Aryan dream by winning the 100m-200m double, long jump and 4x100m relay.

Owens encourages Norman, unlike his words to fellow US athletes, where he speaks of the perils of a potential protest.

Carlos quickly realises Owens had been gotten to by IOC president Avery Brundage, a man who would be judged by history as both racist and anti-sematic.

Owens’ comments only serve to galvanise Carlos and Smith.

OCTOBER 16, 1968:

The biggest day in Norman’s athletic life arrives with him drawn to run against Carlos in the first semi-final.

After the heats, Norman, finding himself within hearing range of Carlos, refers to him as “the third-string American” due to a slightly disappointing heat time of 20.5sec.

Talk can be cheap and now it was the moment of truth, an Olympic semi-final. The brash American nails the start, displaying rare explosive power to put the race to bed after 60m.

Norman later recalls the talent of Carlos: “Carlos ripped through on the inside and pulled me off my feet. The power that he was putting on the track just tore me apart. But I did close quickly late in the race (Carlos won in 20.12sec, Norman was second in 20.22sec)”.

Soon afterwards, Smith easily wins the second semi-final in 20.14sec, despite pulling a muscle in his groin.

OCTOBER 16 (EVENING):

Smith takes his place in the field after initially believing his Olympic dream is over. Norman draws lane six with the US favourites inside him, and by the bend both Carlos and Smith have made up the stagger and are in front, Norman sits back sixth before his engines start to roll, passing runner by runner, even if Smith has the race won. Closing on the line he realises Carlos is gettable, or that bronze could become silver. A final lunge and he has separated the greatest 200m pair the Games have seen, a 178cm white boy from Coburg between two huge black Americans. And at the time, black and white was sadly still a major issue in world sport.

Smith covers the 200m in 19.83sec, smashing the world record despite the injury. Yet what he, Carlos and Norman are about to do means the race itself fades into obscurity.

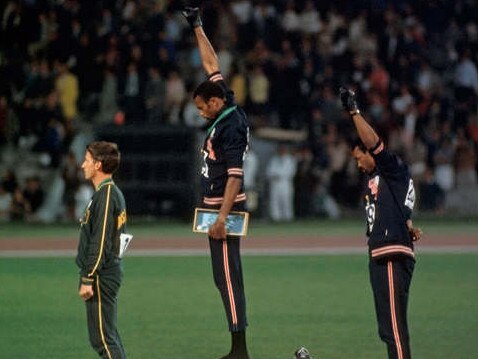

After discussing the reaction for weeks beforehand, Smith and Carlos walk out in socks without shoes to remind the world of the black poverty that exists in the US.

Around Smith’s neck is a black scarf, while Carlos wears a string of beads to highlight the lynchings of blacks.

On Smith’s right hand is a black glove, Carlos wearing the same on his left. They raise their fists to symbolise black strength and unity.

Carlos later tells reporters: “White America will only give us credit for an Olympic victory when they will say I’m an American, but if I did something bad, they’d say I was a Negro.”

Standing alongside them is Norman, someone with the compassion and vision to comprehend the righteous meaning of their actions. But how could he support them?

He asks US rower Paul Hoffman if he could he borrow his OPHR badge, signifying Olympic Project for Human Rights.

He then tells Smith and Carlos “I will stand with you (in support)” and a lifelong friendship is formed. As Smith is introduced first, Norman warmly applauds, unaware as to the enormity of reaction about to unfold.

The International Olympic Committee is outraged, demanding the immediate expulsion of Smith and Carlos, an order the US Olympic Committee initially ignores.

When the IOC threatens to ban the entire US track and field team from further competition, the US complies, leaving Smith and Carlos to face the music back home.

It begins years of criticism, even if the world as a whole is more sympathetic to their actions. One US columnist refers to the pair as “black-skinned storm troopers”, while the pair find work hard to find.

In time attitudes soften and even turn to admiration, but for many years Smith and Carlos pay a huge price for their stance.

OCTOBER 17:

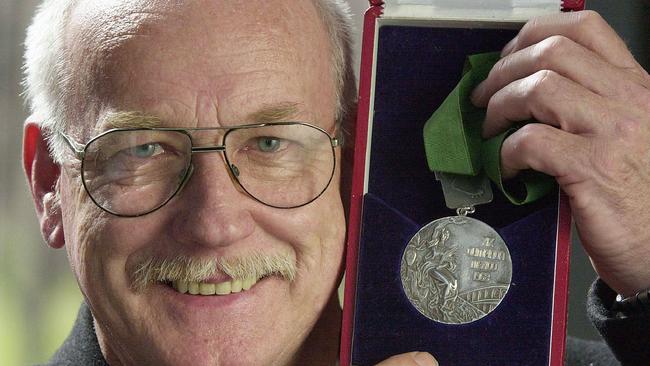

Norman awakes, his mind in a haze, as the fastest white man in the world after his time of 20.06sec in the final, one that would remain as the national record in 2018.

But there is a problem as team manager Judy Patching explains to Norman.

“Some are after your blood for wearing the badge,” says Patching, who is regarded extremely highly as a man of principal.

“So consider yourself reprimanded,” says Patching with a smile.

JULY, 2000:

Thirty-two years have passed since the three men stood alongside each other in Mexico City, and for Carlos that time has proven that white men can be honourable.

“To wear the badge as a white individual, it made the statement even more powerful. During a crucial time in our lives, Peter Norman was compassionate, understanding and he showed his manhood. I’ll always respect and love him for that. Pete became my brother at that moment. A lot happened back then, the most amazing thing being I didn’t know there was a white guy who could run that fast.”

In the same year, Life magazine and Le Monde vote the picture of the trio on the dais as one of the most iconic of the 20th century.

OCTOBER 3, 2006:

Aged 64, Norman dies of a heart attack while mowing lawn in Williamstown, seven weeks after bypass surgery.

Six days later his funeral is held at the Williamstown Town Hall, Norman’s coffin being carried from the hall to the sounds of Chariots of Fire.

Two of the man holding that coffin are Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the latter recounting his memories of that fateful night in Mexico City.

“Not every young white individual would have the gumption, the nerve, the backbone, to stand there. We asked Peter before we went out ‘do you believe in God?’. He said he believed strongly in God. We knew that what we were going to do was far greater than any athletic feat. Peter said ‘I’ll stand with you’. I expected to see fear in Peter’s eyes but I only saw love. Peter never flinched on the dais. He never turned his eyes, never turned his head. You guys have lost a great soldier. Go and tell your kids the story of Peter Norman.”

After hearing the news of Norman’s death, the US Track and Field Federation proclaims 9 October 2006, the date of his funeral, as Peter Norman Day.

The Peter Norman Story by Andrew Webster and Matt Norman, published by Pan MacMillan on Tuesday, RRP $34.99.