Neale Daniher awarded Queen’s Birthday Honour

Football legend Neale Daniher is humbled to receive a Queen’s Birthday Honour, but he admits there is one thing he wants — a cure for MND.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Neale Daniher didn’t think he would get to 60. When he did, early this year, he celebrated with a month of festivities.

The highlight was when 120 family and friends gathered in a city restaurant.

His four children, as well as Neale’s sisters, told stories about the times when Neale had got it wrong.

The crowd heard how Neale — made an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in the Queen’s Birthday honours — once forgot then eight-year-old daughter, Bec, at a little aths carnival, and how son Luke smiled at his sister through the car window as Neale drove away.

The guests heard how Neale almost electrocuted his father, Jim, by connecting the faulty plugs of a welder.

They heard how a farm boy, imbued with farm toughness, was hopeless on a farm.

This desire to find the funny side largely explains Neale’s approach to his very public battle with motor neurone disease.

If his speech has dimmed, his humour has not.

Finding the lighter side in a crisis also helps explain the enduring strength of his 41-year partnership with wife Jan.

It wasn’t love at first sight. They met at a mutual friend’s 21st birthday party near Horsham. Neale, an emerging star at Essendon, didn’t seem like other footy players.

He wasn’t “up himself”, thought Jan, who had never attended a VFL (AFL) match.

They kept meeting back in Melbourne, sometimes at an East Melbourne pub with friends. Essendon, his base, seemed far from Blackburn, where Jan was raised.

“I used to catch the train to the city, I was studying teaching, and I had to walk up Swanston St and he was driving down Swanston St to go to RMIT,” she says.

They valued the same things: a desire for kids, tight-knit family bonds and a shared belief that hard work best fixes a problem.

A love of sport (netball for Jan) bound them. As did the instinct to poke fun at one another: as Neale still reminds his wife, he was right to pick her and she was “very lucky” to get him.

The wedding, in 1985, didn’t go as hoped. Jan’s family were Uniting Church, Neale’s Catholic, so the couple chose a non-denominational church service at Monash University. Depending on who you believe, one or both sides of the family was unhappy with the choice.

Both recall the births of children Lauren, Luke, Bec and Ben as they fitted into the three knee reconstructions that Neale underwent while playing football.

He was Essendon’s best and fairest player at 21. All four Daniher brothers played for Essendon in a 1990 match against St Kilda in an unprecedented display of family prowess.

But his wonky knee cruelled the deserved accolades.

He was an intense young man, an admitted “hard arse”, unlike brother Terry, who joked to and from the ground so much Neale would travel separately to games.

Neale carried the family’s funny gene, but he turned it on and off.

His farm heritage at Ungarie in NSW also ingrained a philosophy he applied then, as now: “There’s always someone worse off than you.”

Jan thrived when the family moved to Perth in the 1990s.

She relished the warmth and the beach.

Neale was an assistant coach at Fremantle, and Jan saw the stresses of the job on head coach Gerard Neesham and wife Heather.

After Neale accepted the head coaching job at the Melbourne Demons in 1998, the pressure was unrelenting.

Each day, Neale would go to work at 8.30am, come home about 7pm, then study opposition teams until about 11.

Watching the Neeshams at Fremantle hadn’t prepared Jan for the demands.

“Neale was really good because he never really brought it home,” she says. “It wasn’t obvious that he was angry or sad. The way to get through it was to work hard and so that’s what he did.

“We had a few times when it as pretty difficult for the kids at school. I used to worry like crazy about Melbourne winning because you knew what the outcome would be if they lost too many games. I found it stressful going to watch the games and I think a lot of coaches wives would be the same. There was nothing you could do.”

When Neale, who had come to be known as “The Reverend”, was asked to reapply for his job in 2007, the pair interpreted the requirement as “morse code for ‘move on’.”

Neale resigned. He wanted to coach an AFL team again. But in an era of younger coaches, he felt his “card had been stamped”.

MND took them by surprise. They both dismissed the weakness in Neale’s hand from 2012. At the time, Jan figured that Neale was “just sooking”.

A typical MND prognosis is a couple of years of life, not eight. Jan now calls what has been dubbed the “beast” and “the bastard” as the “moving beast”.

“We didn’t really know what the disease was,” she says. “We’d heard the title MND, but everyone had to get in and have a look and see what it really was. The having to tell people was pretty awful.

“When he was diagnosed (in 2013) he was actually really healthy, training twice a day. If he wasn’t at the footy club we’d be doing run throughs at the local park.”

They were back living in Perth at the time, and it was during a long flight that Neale inwardly grappled with the MND diagnosis.

“Mr Negative” outplayed “Mr Positive”.

Yet the couple’s innate reflex to find positives helped, as did the demoralising experience of knee reconstructions in his playing days.

“When one of you is diagnosed with a terminal illness, which is something you just cannot comprehend, there’s a lot of thought that goes into how you keep living your life,” Jan says.

“You could sit and be really sad all the time and it could be a terrible way to live. To be able to still find some fun and have a laugh has been really, really important.”

Neale, a beanpole, appears to walk freely. His upper body, from breathing to speech, continues to deteriorate.

It’s second nature for Jan to interpret the now muffled words of her husband.

The diminished speech oddly seems to accentuate Neale’s boyish grin and mischievous twinkle. You know the next joke is coming before he delivers it.

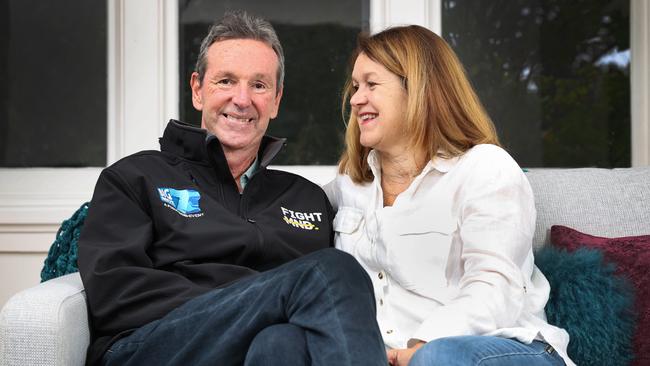

The couple sit on the loungeroom couch together, slightly worn out by the now annual blitz of media commitments before the Queen’s Birthday game and the Big Freeze.

There is lots of laughter, mostly gentle ribbing of one another. They also speak of the day-in day out difficulties, “the moments” when patience wanes and frustrations soar.

This year Neale celebrates not only the Big Freeze but his Queen’s Birthday honour — one he dedicates to family.

“As a family we’ve learnt that life is fragile and all the possible beautiful things in your life are not guaranteed to be there tomorrow, so look out for them and enjoy them when they arrive. Play on,’’ he says.

“While I am incredibly honoured to have this award, we don’t need any more awards, we just need to find a cure.’’

Jan says: “None of this would be possible without all the people who have supported us around Australia.”

“You don’t do anything or any work like this to expect anything from it,’’ she says.

“You just have a focus and that’s what we have.’’

Neale’s happiest times are with the bigger family. Granddaughter Rosie is a regular visitor to their Canterbury home.

She and her grandfather bop together to songs of his choosing. The unyielding deterioration in Neale’s physical health compels him and Jan to focus on what they have, as opposed to what they do not.

Acceptance of the daily hardships, and the dimming future, have honed lessons they’ve learnt together since they were both 20.

They seek to get past differences of opinion. They look to forgive after an argument, and a foundation of their bond is the abiding ethos to “get over it”.

“Going through life you learn not to worry about little things and you learn that you just have to get on with life and not take anything too much to heart,” Jan says.

“I think we balance each other pretty well. Neale’s the funny guy so he always keeps it light. And he’s got funnier. He’s hilarious.”

At this, Neale stirs. “It’s just taken everyone a while to realise,” he says.