Mitchell Toy: John Pomeroy’s explosive ammunition helps bring down German WWI forces

Known as the man behind Melbourne’s pie “institution”, it was old John Pomeroy’s hidden talents that wreaked havoc on the Kaiser’s WWI war plans.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Melburnians who lived a century ago are much the same as Melburnians today, in one certain regard: they love a warm savoury snack after a big night out.

These days it’s souvlaki and kebab vendors who satisfy that need. In decades past, it was Pop’s Pie Cart.

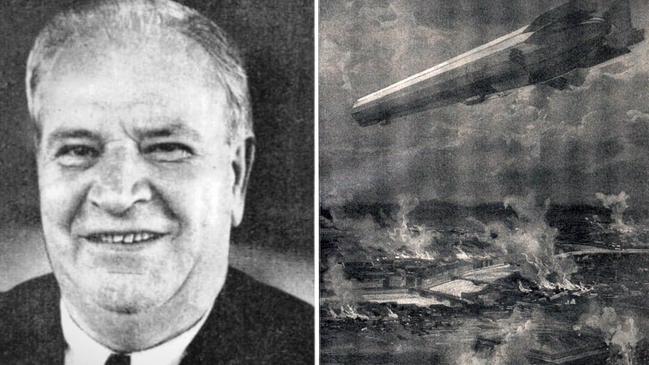

Old John Pomeroy, a silver-haired, chubby and jolly-mannered fellow, would trot his horse-drawn kiosk to the steps of Flinders St Station, roll up the shutters and ply the passers-by with delicious pastries.

Pop’s Pie Cart was an institution to shift workers and night owls alike.

But its humble proprietor had a hidden, and deadly, talent.

John Pomeroy was an enthusiastic inventor who dabbled in gadgets and gizmos of every variety.

During WWI, his clever design for explosive ammunition, concocted in Melbourne, proved devastating against the German forces.

Pomeroy the pie man’s lethal invention led to the downing of more than a dozen enemy Zeppelins, wreaking havoc on the Kaiser’s war plans.

This hidden genius struggled to get his various other inventions in front of the right people, leading to frustration and waste.

Dead Zeppelins

Born in New Zealand in 1873, John Pomeroy worked as an engineer and trawler hand before moving to Melbourne in 1911 at the age of 38.

Already his curiosity and craftsmanship was leading to an extensive kit of knick-knacks.

Pomeroy invented a special type of cricket guard which, when worn by batsmen, deflected fast deliveries so well, it often sent them straight to the boundary.

He had impressive designs for women’s hat clips, a headlamp dimmer and even a painless rabbit trap.

At the age of 17 he had patented a type of clothesline that could never be blown down by the wind.

But his real interest lay with bullets and explosives.

After years of experimentation, and just in time for war with Germany, Pomeroy came up with his most famous invention.

It was an incendiary aircraft bullet that would explode on contact with taut canvas – like the type used on German airships.

His invention was eventually snapped up by the British war machine, and when the first Zeppelin was shot down in September 1916 over London, it was a Pomeroy bullet that did the deed, fired from an aircraft piloted by Leefe Robinson.

Robinson later wrote of his final pass on the aircraft with Pomeroy bullets loaded in his drums:

“I had hardly finished the drum before I saw the part fired at, glow.

“In a few seconds the whole rear part was blazing. When the third drum was fired, there were no searchlights on the Zeppelin, and no anti-aircraft was firing.”

It brought to an end a two-year reign of terror inflicted by the Zeppelins on London.

Long before his pies warmed the hearts of Melburnians, Pomeroy’s explosive bullets certainly raised the temperature of the German air forces.

A combination of the incendiary rounds and new air fighting techniques saw many more airships destroyed, 14 of which were attributed to Pomeroy’s invention.

Pomeroy was paid handsomely for his creation and continued to receive royalties for his other military innovations into his later life.

During WWII, when his passion project, the pie cart, was in full swing, Pomeroy would entertain his customers with thrilling tales about his innovations.

But getting his ideas into production wasn’t always an easy task.

New ideas

As Australia geared up to join the new war in Europe and the Pacific, Pomeroy again suggested his explosive bullets be used in combat.

But the Australian military authorities were reluctant to take them up; they considered it illegal to use explosive rounds against troops on the ground.

“I could turn out the bullets here in unlimited quantities,” Pomeroy claimed.

“I don’t believe in using them against infantry, but in war, one goes out to kill although putting a man out of action would seem to be sufficient.”

Visited by a journalist at his South Melbourne home and laboratory later in his life, Pomeroy expressed his frustration at having the potential of his creations squandered by thickheaded bureaucracy, especially a new type of .505 bullet that was rejected by the Australian Army during WWII.

“Despite the fact that my bullets were already being made in China and the United States, and the Germans were using explosive bullets fired by aircraft cannon, my invention was turned down,” he said.

“Can you wonder at it?”

But never mind.

At the age of 68, Pomeroy would still venture into the hills behind Whittlesea and let off his latest bullet designs, which would rumble in the night like thunder.

And, he had turned his focus to something much more rewarding than ammunition and bombs.

Pomeroy led the journalist to his vegetable garden where he was experimenting with new varieties of rhubarb, strawberries and lemons.

Just as his creations had brought the wrath of fire from the sky, so now did they twine with nature and summon something new from the earth.