Melbourne’s homeless: How do things go so wrong that some people end up sleeping rough?

HOW do things go so wrong that some people end up sleeping rough? These are the stories behind the men and women doing it tough on our streets.

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

A COLD wind picks up about 10pm on an ordinary Thursday and sweeps through Melbourne’s CBD. It’s the kind of night when you just want to get home. But about 300 or so people on the streets already are home. They’re our city’s entrenched “rough sleepers”.

Come morning, city workers will file past them on their way to shops and offices, perhaps wondering how a human could sink so low as to sleep on the street, or perhaps thinking, “There but for the grace of God go I.”

But many of us, so accustomed to the sight of those motionless bodies hidden under heaped blankets on the side of the footpath, won’t think of them at all.

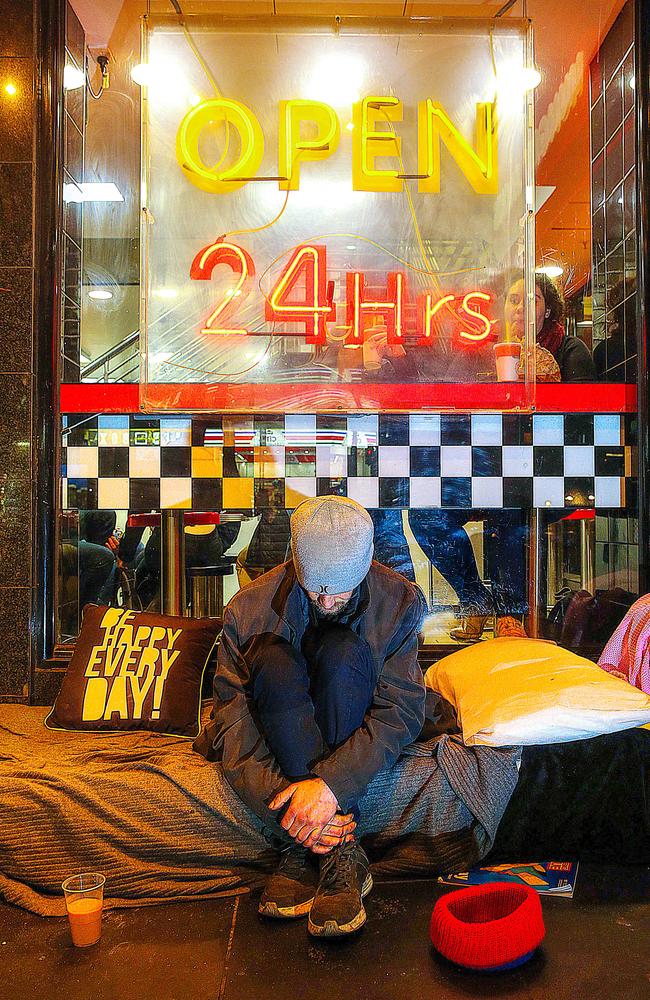

THIS chilly Thursday night, directly beneath the glare of a Bourke St fast food joint, a stretcher is neatly made up with blankets, a pillow and a cushion shouting, “BE HAPPY EVERY DAY!”

But the man on the stretcher (pictured below) is not heeding the cushion’s command.

“No, I’m not happy. I would not wish this life on anyone,” he says.

Aged about 30, he’s painfully thin, has the shakes and speaks quietly but articulately. His sore-looking hands are cracked with dirt.

He was laid off from his job in regional Victoria in the late 2000s, bringing on anxiety and depression.

“I lost my job and car. I couldn’t pay rent,” he says.

He came to Melbourne seeking help from family. He reckons they rejected him, and now, on the footpath in front of him, there’s a hat containing about $2 in silver coins. His few possessions are neatly tucked around him.

In his early days in Melbourne he had a partner but things ended with him jailed for hurting her.

“It was a coward’s friggin’ act,” he says, full of regret. “I came out here after prison.”

On the street, he says, people give him food, coffee, Chinese takeaways. As we speak, a businessman rushes up, shoves a jacket in a plastic bag at him, then hurries on.

“Thanks,” he says, taken aback.

He’s looking for a place to live, but his anxiety makes living in shared housing unthinkable. He could sleep at the Salvation Army’s Bourke St cafe, where dozens bed down each night, but he can’t stand the cramped environment. So he tries to blend in and go unnoticed.

“You can have everything and lose it all in a day and end up out here, and once you’re out here you get stuck. It’s s---,” he says.

Throughout the city, doorways and steps are littered with the detritus of such lives lived without homes.

Weekend hit the street with Samantha Hadfield, an outreach worker with Urban Seed, a Christian organisation based at the Collins St Baptist Church.

Most nights Hadfield and volunteers wheel a sturdy trolley through the streets, stopping to offer coffee, biscuits and a chat.

“It’s not really about the coffee, it’s about the human interaction. We are going to them, to their space and getting to know them. I treat them the way I would my family,” Hadfield says.

The 28-year-old is studying a Diploma of Youth and Community Work with Praxis Training.

She says the hardest thing about her work is seeing the same people on the street as were here when she started doing this work five years ago. By building trust, she hopes they’ll know she’s here to help if they need her.

AS we walk along, we meet a slightly built woman probably no older than 22, wearing a smart blue coat. She doesn’t have time to talk, her legs are tired and she’s pregnant with twins, she says. She’ll sleep rough in the CBD tonight.

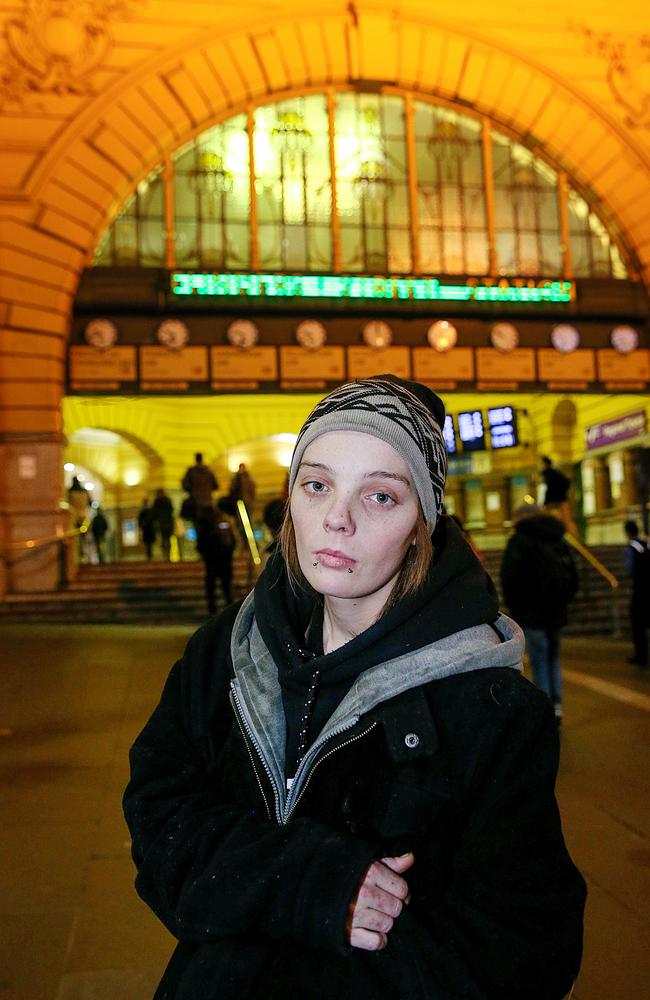

Then there’s Bianca, in her early 20s, who sleeps under a bridge most nights with her partner and two others. Just because Bianca’s homeless doesn’t mean she can’t dream. One day she would like to become a childcare worker or a nurse.

“I’ve been on the streets on and off since 2013.

I want to get off them. I’m linked in with organisations like Salvation Army, Frontyard, Launch Housing and all that, but because we’re a couple, there’s not much support for couples,” she says.

Hadfield tells her a housing case worker was looking for her earlier to say he had found them

a home. But they’ve probably missed out now because he couldn’t find her.

Bianca’s disappointed, but the feeling is not new. She’s had nothing to do with her mother since moving out of their Queensland home aged 15.

She, her boyfriend and some friends rented a house, but when one housemate stopped paying his share, the whole group got kicked out and ended up living on Brisbane streets.

Bianca and her boyfriend came to Melbourne three years ago, thinking it would be easier to get work. It didn’t pan out. Now, to supplement her youth allowance, she puts her beanie out on the footpath and hopes a few coins will land in it. If there’s $40, she can stay in a backpackers; $50 and she can buy a $10 dinner, too.

“People walk past me, call me ‘junkie’, step on my stuff. I get ignored by people,” she says. “Even if they don’t stop and give me money, it would be nice to have a chat. Some homeless people are aggressive, but not all of us.”

WE also meet Roger, 39, a stepdad of three who was staying with his parents until they got sick of his drug use and kicked him out.

“I pushed my mum and dad. I feel really bad. It was over bulls---. They pushed me over the edge,” he says.

Roger’s a tall bloke with a swagger. He’s hanging out with four mates on the steps of a Bourke St business.

While the boys drink cask wine, smoke dope and give him cheek, he tells me he grew up at Chirnside Park, out east. Now he’s couch surfing, sometimes staying at a mate’s place in Ringwood, sometimes on the streets. He’s one of the “hidden homeless”.

“I’m staying everywhere. And I’m trying to get a job,” he says.

Roger says he used to be a firefighter, and he used to own a car, until he wrote it off.

“I’ve always had a s--- life. I’ve been pushed through the system.”

He reckons he’s been in trouble with the police ever since becoming homeless.

“I want to go to rehab,” he says, adding he’s getting help from Hillsong Church. Roger happily accepts Urban Seed’s coffee.

FURTHER on, Enterprize Park on the banks of the Yarra is virtually deserted. Not long ago there was a small tent town there under cover of huge railway bridges opposite glitzy Crown Casino.

Now, a woman with a weathered face sits on a sleeping bag smoking dope with a friend. Despite being virtually incoherent, she is determined to speak and launches an emotional breathless stream.

“I feel like I’m not accepted in society. I’ve got depression and psychosis,” she says. She hears disturbing voices. She feels suicidal.

“I’m better than this,” she stammers emotionally. She looks about 35. “This is sucking the life out of me man. Nobody’s here to help me.”

This winter the Salvation Army has opened the doors of its Hamadova Cafe in Bourke St at night, providing a warm space for 80-90 people to bed down.

One regular is a downy-faced lady in her 80s, homeless since her inner-Melbourne house burnt down three years ago. She has a trolley of belongings, a stylish hat, long warm coat, and looks like anybody’s grandma. She walks everywhere, including down to the St Kilda Salvos for toasted sandwiches.

“I have got no home,” she says.

Out on the street, people are settling in for the night on Flinders St’s wide footpath beneath the train station awning.

We meet Avan. He says he’s 28, but his worn face makes him look at least 15 years older.

“I’m all right,” he says, smiling and friendly.

But anybody can see he is far from all right. Avan arrived from Perth in late July, his mother having paid his fare to help him escape an ice habit.

He has the best intentions, but it’s been a long time since Avan’s life went according to plan. Avan says his father died in a traumatic way when he was just 12, then his stepfather also died.

He’s been sleeping rough on the streets, on and off since age 17. The former grapevine pruner has schizophrenia and has spent time in psychiatric wards. His medicine makes him dopey but he says he usually takes it, and promises to renew his prescription before it runs out.

“I’m trying to get off the ice. I’m drinking alcohol and I’ve got pains in my guts. But I’ve been a week off it,” he says proudly.

Living on the streets is OK, but it can be lonely, he says. “I’ve found some good friends.

They’re nice people,” he says motioning to a couple a few metres away, huddled together under blankets.

Avan has an uncle and aunt in Mt Beauty but is reluctant to seek their help.

“It’s near the snow, I’ve never seen the snow before. But I don’t want to go there all f---ed up, because they’ve got kids. I’m pretty messed up.”

Within a week of arriving in Melbourne, Avan had his first taste of heroin.

“My friends had to carry me everywhere, it was pretty bad.”

With pedestrians rushing by all day long, Avan says his overwhelming feeling is suicidal.

Hadfield asks how he’d feel going back into hospital.

“Yeah, it does help me, but as soon as I get out, I f--- up again”.

As Avan shares his sad story, a passer-by offers him a container of fresh pasta.

“Na, thanks mate. I don’t take stuff if I don’t need it,” he explains.

He’s reading a paperback of Alistair McLean’s Ice Station Zebra and has oranges, bottled water and warm blankets on his stretcher.

“I feel like my life is on pause and I’ve got nowhere to go. I want to have a job and be normal like everyone else, and have a missus. I want to be happy.

“But my laugh is a fake laugh. I’m trying to laugh, but it’s not real.”

A few days later Avan has moved on, and a new stretcher and pile of blankets have taken his place on the cold stone footpath outside Flinders St Station.

Anyone struggling with depression should call Lifeline on 131 114 or beyondblue on 1300 224 636

THE FACTS

— 22,773 Victorians are without a home every night.

— One in 10 Australians experiences homelessness in their lifetime.

— In June, 32,250 people were on the public housing waiting list in Victoria.

— Homelessness includes those who sleep rough (5 per cent); in rooming houses (19 per cent); in overcrowded dwellings (27 per cent); couch surfing (15 per cent); supported accommodation (34 per cent).

— 44 per cent of homeless Victorians are aged under 25 and 26 per cent

aged under 18.

— Last year, 102,000 Victorians sought help from homelessness services,

up 10,000 on the previous year.

— Almost half of people seeking help are families with children.

— 38 per cent of people needing help said “family violence” was the

main reason.

— Across Melbourne’s suburbs, only 6 per cent of all private rentals would

be affordable to someone on a low income.

— 850,000 Australian households are in “housing stress”, spending 30 per cent of their low income on rent.

Sources: Census and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare via Victoria’s Council

to Homeless Persons