Melbourne’s forgotten mansions: Inside stately homes now destroyed

NOT all of Melbourne’s grand mansions have survived the tides of time. We look at what life was really like inside these epic houses.

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

GIANT archways, stone columns, gothic exteriors, stained-glass windows, elaborate staircases and marble floors once decorated some of Melbourne’s grandest homes.

Yet not all of these grand homes — that were staffed by small armies of maids, cooks, nannies, wet nurses, governesses, gardeners and stable hands — have survived the tides of time.

But what was life really like for those who lived and worked in these mansions?

1930s: PHOTOS REVEAL WHAT MELBOURNE LIFE WAS REALLY LIKE

GLORY DAYS: MELBOURNE'S GRAND OLD BUILDINGS THAT NO LONGER STAND

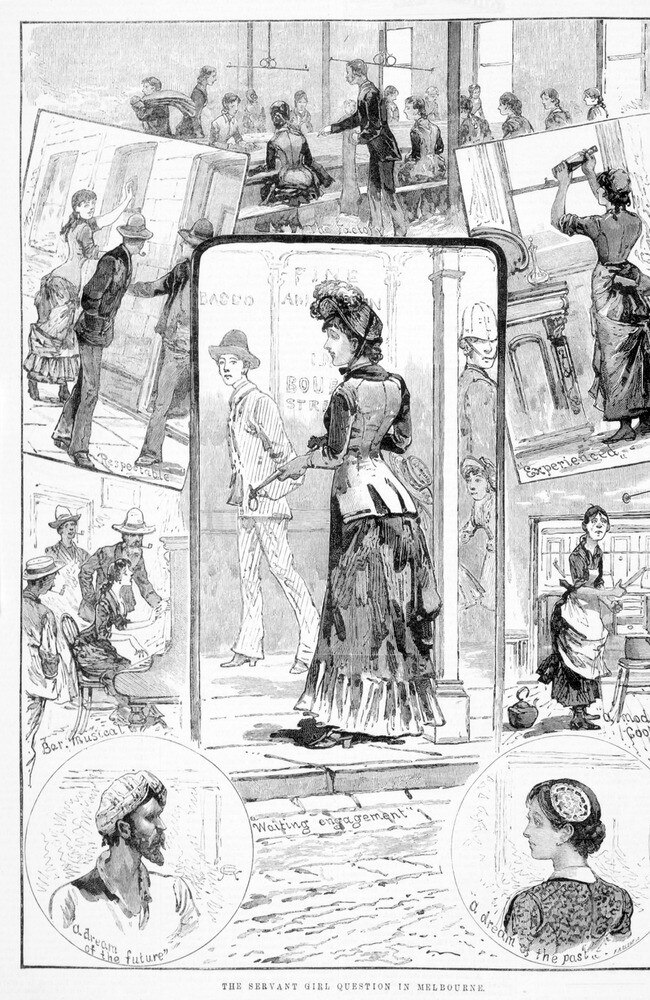

For much of the 19th and even part of the early 20th centuries, these opulent houses were one of the main forms of employment for women in Victoria.

“It (being a paid servant) was a big industry,” said Professor Shurlee Swain, an ACU academic who specialises in women’s history.

Unmarried women, but also females who were wards of the state or came before the courts, served as maids, cooks, cleaners and servants in these grand mansions.

A life in service began for most women at age 14 and continued until they married, though there were some avenues for work that could be taken home once a women married.

Service jobs provided many women with a roof over their heads, clothing in the form of uniforms and free food.

“They (women in service) were considered provided for as they were fed and clothed,” Professor Swain said. But wages were low and the hours were long.

“They started work hours before the house got up and they kept working until the house went to bed,” she said. Days off were rare, though in some households, servants with family were given a day off.

Some servants were day staff who lived in small cottages in laneways at the edge of the estate, while most others lived on site.

While many readers will be familiar with the respectful relationship between servants and their masters on TV’s Downton Abbey, the reality was much more complex.

Mistreatment wasn’t widely reported as many servants were totally economically dependent on their bosses.

“There was no room to complain, unless you’d worked out an escape plan,” Professor Swain said.

Most maids or servants didn’t dare ask for pay rises, as they feared losing their jobs.

“They were terrified of the repercussions,” she said.

Those who worked in service needed references from former employers prepared to vouch for both their skills and their moral integrity in order to get another job.

Women in these manor homes were also vulnerable to sexual relationships with the man of the house or other male domestic servants — whether they welcomed such advances or not — yet concealing an unwanted pregnancy would have been near-impossible.

“These girls didn’t have the resources to hide what had happened to them,” Professor Swain said.

Servant employment agencies often advertised these unexpected babies for adoption in major newspapers.

These babies weren’t involved in closed adoption as the mother often knew where the child went and had a “fighting chance” to reconnect, if they later married or earned enough money to provide adequate care.

Experts estimate 60 per cent of indigenous girls who went into service in NSW and Queensland became pregnant — from either the master, his sons, or the other hired help — and Professor Swain said female Aboriginal domestic workers in Victoria would have also faced unwanted pregnancies at a similar rate.

Domestic servants could also get work as wet nurses and nursery workers, though this too was fraught. Victoria’s rich and famous carefully scrutinised the employment history and moral fibre of wet nurses, as they wanted to ensure their children were getting the best care.

Unlike England, most elite households here employed few to look after the children and often British guests complained at how often they had to see the family’s children. Australian mothers were renowned for looking after their own babies.

For the few who were wet nurses, particularly in the 19th century before baby formula was safe, many breastfed the babies of rich employers while their own often failed to thrive or died.

Beginning in the 1920s and continuing into the post-WWII period, domestic service began to decline as families struggled to afford such lavish lifestyles.

“Very few households could sustain the cost,” Professor Swain said. “You generally saw people making do with few servants.”

“The family may have been wealthy, but couldn’t afford the cost of servants and the cost of maintaining their properties,” she said.

Not all of Marvellous Melbourne’s grand mansions and estates are still standing.

Here are the stories behind some of these magnificent homes that have since been demolished.

GOTHA

ALSO KNOWN AS: Hadleigh Hall.

LOCATION: Kensington Rd, South Yarra.

BUILT IN: This 17 bedroom home was created for Hugo Wertheim in 1886.

He made his fortune importing sewing machines and pianos from Germany, before opening a piano factory in Richmond.

The house was said to cost 40,000 pounds to build and was designed by architect Charles D’Ebro.

The house originally featured multiple bathrooms for the family plus another for the help, this was unusual as the house predated Melbourne’s sewage system.

HIDDEN HISTORY: Wertheim died in 1919 and the house and its contents were auctioned off separately in 1923.

A report which appeared in The Argus on 20 June 1935 said the house was being turned over to the wreckers as “few in these days can afford to employ the large staff of servants necessary to maintain such a mansion”.

The advertisement for the sale described the magnificent property as: “A splendid two-storied brick and cement residence with a frontage of 259 ft (78.9m) to Kensington Rd and 310 ft (94.4m) to Como Ave with a depth of 350 ft (106.6m).

“The superb residence was built and decorated by the well known architect, the late Mr C.A. E’Bro and contains: Ground floor — large drawing room divided into rooms by sliding doors, a sitting room, dining room, opening on to conservatory, beautiful billiard room, lavatory, butler’s pantrv, storeroom, maids’ dining room, large kitchen and scullery, shed with white tiles, tiled larder, hot water service.

“First floor — six large bedrooms and four bathrooms, large day nursery, sleep-out, linen room, four maids’ bedrooms, and bathroom. Brick and cement outbuildings with man’s bathroom, coal room, boot room, brick stable with room for two cars, hothouse, fowl house and tastefully laid out lawns and flower beds. Excellent grass tennis court.”

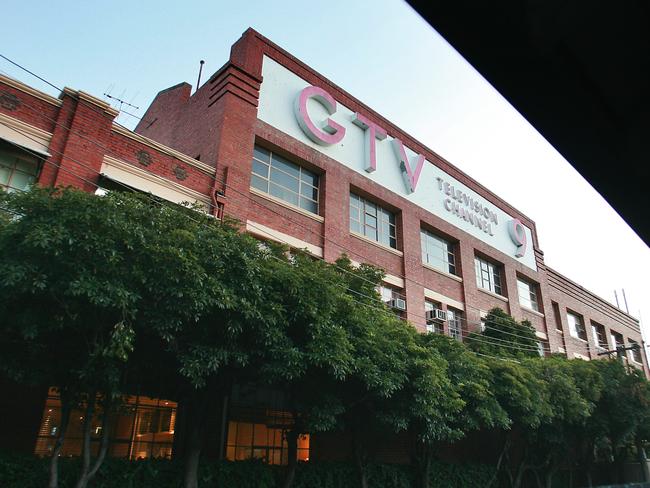

WERTHEIM PIANO FACTORY

The Wertheim piano factory was located in Bendigo St, Richmond until it closed in 1935, when it was sold to Heinz who later sold it to Channel 9 who used it as the station’s Melbourne HQ where shows such as Hey Hey It’s Saturday were filmed.

Jeff Kennett is also a great-grandson of Hugo Wertheim.

TORN DOWN: In 1935 the land including the mansion was subdivided and the property was earmarked for demolition.

SITE CURRENTLY USED FOR: Housing. Four blocks of apartments were built on the site in the 1940s.

NORWOOD

LOCATION: The Esplande, Brighton.

BUILT IN: Construction on the site was completed in 1891.

The 14-bedroom mansion situated on two acres was designed by Melbourne architect Philip Treeby for financier Mark Moss.

By 1890 he was thought to be worth 500,000 pounds but after the economic crash of that decade, he reportedly died in 1901 with just 20 pounds to his name.

Advertisements for the sale of the house and contents, placed in The Argus included a description of the 35-panel three-section stain glass windows depicting Shakespearean characters said to be the “finest window in the Commonwealth”.

HIDDEN HISTORY: In 1894 the Bank of Victoria repossessed the property from Moss and sold it to Richard White.

Moss’s son Harry established a generous bequest for the Royal Children’s Hospital.

Since Harry’s death in 1960, the perpetual trust has distributed over $40 million to the hospital.

Norwood passed through several owners and the last family who owned it are said to have turned down an offer to turn the house into a reception venue.

More than 7000 Melburnians visited the mansion, described as castle-like, before it was torn down.

The gatehouse, now known as Belle Vue, has survived and was relocated to Norwood Ave, Brighton.

TORN DOWN: Demolished after the property and its content were auctioned off in 1955. The property was subdivided into 12 blocks.

SITE CURRENTLY USED FOR: Housing.

TRAVANCORE MANSION AND ESTATE

ALSO KNOWN AS: Flemington House.

LOCATION: The Travancore estate was situated on Flemington Hill bound by Mt Alexander Rd, Moonee Ponds Creek and Baroda St.

BUILT IN: Built for Hugh Glass after his 1852 marriage to Lucinda Nash at a cost of around 60,000 pounds. Mr Glass had purchased the property which had a smaller house on it from squatter James Watson.

Workmen spent over two years on the site replacing the original house with the mansion and Mr Glass’ brother-in-law was sent to London to buy suitable furniture and fittings.

The mansion had a grand ballroom said to be the size of a town hall and there was an artificial lake which was home to ducks, white swans and cranes.

The mansion had two staircases, a gymnasium, library, drawing room, sitting room, 24 fireplaces, two upstairs bathrooms, eight family bedrooms, a 72 pillar balcony, kitchen, dining room and sewing room. Other buildings on the site included a gatehouse, a boathouse, a summer house, stables and servants’ quarters.

The 25-acre grounds included orchards, numerous glasshouses and avarie.

HIDDEN HISTORY: Mr Glass established the Tahbilk vineyards in Nagambie and in the 1860s with a net worth said to be around 800,000 pounds the merchant and squatter was widely thought of as the richest man in Victoria.

In 1907 the property was purchased by Sir Henry Madden who later subsided much of the estate and retained the house and another 60 acres.

The remaining estate was subdivided in the early 1920s before the vacated house and the remaining nine acres were purchased by the state government in 1926. The mansion reportedly cost the government 11,000 pounds.

The government purchased the property to create a residential school for intellectually disabled children.

The ornate iron gates that marked the entrance to the estate still stand on the site and now mark the entrance to Flemington Primary School.

TORN DOWN: In the 1940s.

SITE CURRENTLY USED FOR: The estate’s extensive land now houses 1700 residents in homes, flats and townhouses.

Many of these homes were built in the 1920s and are listed on the National Trust’s heritage database as examples of art deco housing.

Part of the large site is also home to the Travancore mental health service as well as Flemington Primary School.

NAREEB

ALSO KNOWN AS: Oma.

LOCATION: 166 Kooyong Rd, Toorak.

BUILT IN: In 1888 Nareeb was built for piano manufacturer Octavius Charles Beale.

The home was designed by architect William Salway who also designed Raheen.

Built to house Beale’s 13 children, the Italian-style mansion featured an ornate entrance hall, a smoking room, dining room, drawing room, music room, breakfast room, sewing room, bedrooms and servants’ quarters.

The majority of the house’s furniture was imported from England, bar the 16-piece Australian blackwood dining suite.

The 34 lavishly decorated rooms in the house included the entrance, drawing room, first floor balcony and main hall.

The house hosted many glittering parties and balls to mark events such as the Spring Racing Carnival as well as birthdays and milestones of the families who called the mansion home. These elegant soirees usually made the social pages of newspapers such as The Australasian and Table Talk.

HIDDEN HISTORY: More than 1000 people viewed the house, its antique collection and grounds on the day it was auctioned off in 1965.

When the house was sold it was still powered by gas lights.

The house’s gates were donated to the Royal Botanic Gardens by the National Trust in 1967.

TORN DOWN: In the late 1960s, after the house and surrounding 5.5 acres were subdivided to make way for Nareeb Court upon the death of the remaining Simmons heir.

SITE CURRENTLY USED FOR: Housing.

ARMADALE

LOCATION: 416 St Kilda Rd.

BUILT IN: Designed by Crouch and Wilson for draper, retailer and furniture merchant Thomas Moubray in 1867.

Elected to the city council in 1865, in 1868 Moubray was made mayor.

He also served as a director and chairman of the Commercial Bank of Australia and deputy chairman of the Metropolitan Gas Co.

He also served on the committee of the Melbourne Hospital and the Mechanics Institute

After his death in September 1891, his 188,900 pound estate was divided between his nieces and nephews and his wife was given a lifetime interest in Armadale and an annuity of 1500 pounds. The couple had no children.

The mansion itself contained 11 rooms over two storeys.

TORN DOWN: In 1976 to make way to make way for a 27-storey office block.

SITE CURRENTLY USED FOR: The City Condos apartment building.

HEATHFIELD

ALSO KNOWN AS: Wombalano.

LOCATION: St Kilda Rd.

BUILT IN: In 1884 at a cost of 20,000 pounds designed by Richard Twentyman and David Askew Bruce with the help of artist Robert Reid.

The 30 room property was built for merchant John Munro Bruce and the five-acre site originally included a tennis court, coach house, stables and a carriage-drive.

The house was designed to be an imposing stone mansion with “one of the finest panoramas of the neighbourhood of Melbourne”.

The mansion had a formal dining room, library, children’s school room, nursery, billiards room, in addition to bedrooms and sitting rooms.

The gardens also included a grass tennis court, flower garden and vegetable patch.

HIDDEN HISTORY: The house became one of many fine mansions sold after the 1890s crash. It passed through several hands before it was purchase by Mrs Bertha Baillieu in 1911.

In 1933 the house was sold to Sir Keith Murdoch whose son Rupert own News Corp, the company which published this article.

During WWII, the home was used by the US Air Force.

After the war the property was used by the Salvation Army and later nurses working at the Royal Children’s Hospital stayed at the house.

The house’s gates survive to this day.

TORN DOWN: In 1958 after being sold to a developer. It made way for the second stage of building for Kenley Court.

SITE CURRENTLY USED FOR: Housing.

CHANTRELL

ALSO KNOWN AS: Tower Villa, Tower House and Invercloy.

LOCATION: 36-38 Margaret St, Moonee Ponds, though it is listed at 28 Margaret St in some records.

BUILT IN: On a four and a half acre block in 1880 for grazier Francis Williams.

This grand home had a drawing room, dining room, five bedrooms, bathroom, kitchen, scullery, pantry, library, breakfast room, the smoking room was originally located in the tower and the property also featured a courtyard, gardens and large fountain.

The house passed through many hands and from 1912 was used as a medical practice by several prominent local doctors beginning with Dr Septimus Strahan.

In 1953 Dr Montagu Kent-Hughes and his family added a ballroom as part of the family’s efforts to restore the property to its former glory.

HIDDEN HISTORY: When the house and its antique contents were put on the market in 1934 following the death of Dr Strahan, the list of items for sale to the general public included a solid mahogany 18 foot oval end dining table, a marble and bronze timepiece, and an 8 foot library bookcase.

TORN DOWN: Sold to a developer in 1980 for $222,000, the property was demolished a year later without a permit and the developer was fined $200. The property sat near Moonee Ponds train station and some angry locals claimed the house was torn down to make it easier for developers to have the land rezoned for commercial use to build a supermarket.

The local council later approved plans to build units on the site.

SITE CURRENTLY USED FOR: Retail and office space.

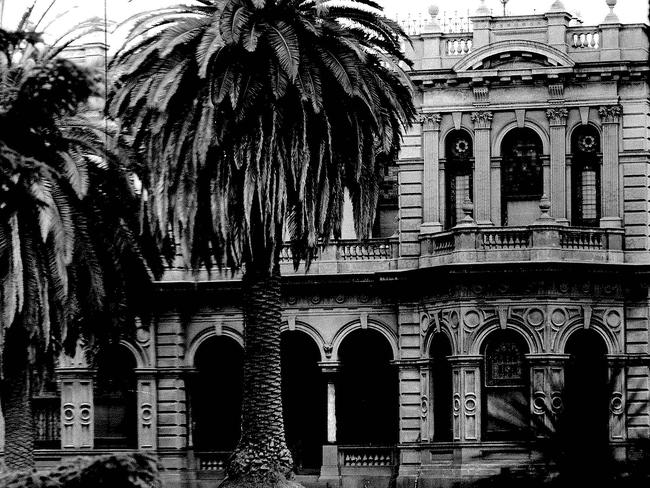

CLIVEDEN MANSIONS

LOCATION: Wellington Pde, East Melbourne.

BUILT IN: In 1887 for baronet and pastrolist Sir William Clarke as his grand city home. His 50-room Sunbury mansion Rupertswood, home of the Ashes urn, was built between 1874 and 1876.

The Italian Renaissance style building was designed by architects William Wardell and W.L. Vernon.

HIDDEN HISTORY: The ballroom built as part of the original design was said to hold up to 250 people.

The property was sold to the Baillieu family in 1909 and a fourth storey was added before the home was converted into 48 up-market individual apartments.

There were no kitchens in these dwellings, instead a dining room staffed with waiters and a French chef catered to the needs of residents and their guests. The apartment block also boasted a shared garage.

A broken water pipe caused large-scale flooding damage to the property in 1948.

It took firemen several hours to clear water from the site and many valuables had to be placed on the sidewalk as they worked.

TORN DOWN: In 1968.

SITE CURRENTLY USED FOR: Hilton Hotel.