Melbourne researchers design new 3D-printed hand

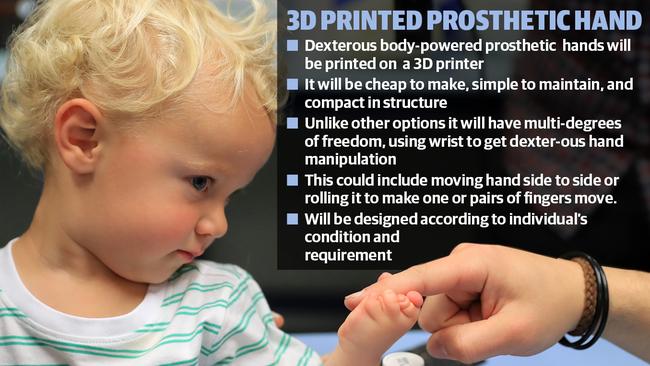

A NEW 3D-printed hand designed by Melbourne researchers will give patients an affordable, practical and durable artificial limb powered by their own body.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A NEW 3D-printed hand designed by Melbourne researchers will give patients an affordable, practical and durable artificial limb powered by their own body.

The device will be a 10th of the price of a hi-tech hand prosthesis and allow spare parts and bigger sizes to be made quickly and cheaply.

But the biggest perk for patients will be the expanded range of movement, enabling them to pick up small or irregular objects such as a pen or a ball

Victorian toddler Harlow Bowden, an adventurous two-year-old born with no fingers and only half a thumb on his left hand, will test the device.

“During ultrasounds we were told he had 10 fingers and toes, but we later learned that they only count toe stubs and knuckles,” his mother, Chloe Horsburgh, said.

Trialling a child-sized version of the university’s design while Harlow was still young was an appealing prospect.

“The brain can wire itself to use the prosthetic as part of their body and it becomes a part of his life,” she said.

Monash University’s Lisa O’Brien, an occupational therapist specialising in hands, said people missing fingers or hands needed improved prosthetic limbs.

“We know that children in particular outgrow or break their prosthesis really quickly and they tend to abandon the hi-tech myoelectric ones because of the cost and complexity of fixing them,” Dr O’Brien said.

“They need something that is robust that can be fixed quickly and easily by their practitioner or parent.”

The device could also help patients in developing countries who cannot afford the hi-tech devices, which can cost $8000-$50,000.

Cheap and easy to assemble 3D-printed prosthetic hands offer limited movements.

“They tend to be only one degree of freedom in terms of motion: either all fingers open or all fingers closed,” Dr O’Brien said. “There isn’t the ability to isolate a pincher grip, using the thumb and the index finger, which is important for people able to hold a pen, or achieve a point gesture, so that children can use a keypad.”

That’s where the expertise of engineer Dr Chao Chen, who is partnering Dr O’Brien on the project, comes in.

“Currently the existing simple 3D printed hand has only one degree or movement: using the bending of the wrist to open and close the hand,” Dr Chen said.

“We want to be able to offer the user more functions by allowing the fingers to work autonomously without electrical activators or a battery.”

Their first prototype will soon undergo patient testing and refinement after receiving a grant from the Monash Institute of Medical Engineering.