Meet the real Madame Brussels, dubbed the wickedest woman in Melbourne

YOU’VE probably had a drink at Madame Brussel’s or walked the lane that bears her name, but who was the woman once dubbed Melbourne’s queen of harlotry?

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

MADAME BRUSSELS was the most influential businesswoman in Melbourne in the late 1800s, amassing an enormous hoard of properties and cash.

She had politicians and police wrapped around her little finger, and managed to build an empire that thumbed its nose at the religious puritans of the Victorian era.

She was — as many know — a famous brothel owner.

But her immense success in such a seedy industry drew the attention of religious types and conservative journalists who made it their mission in life to bring her down.

NICKNAMES FOR AUSSIE CROOKS & COLOURFUL CHARACTERS

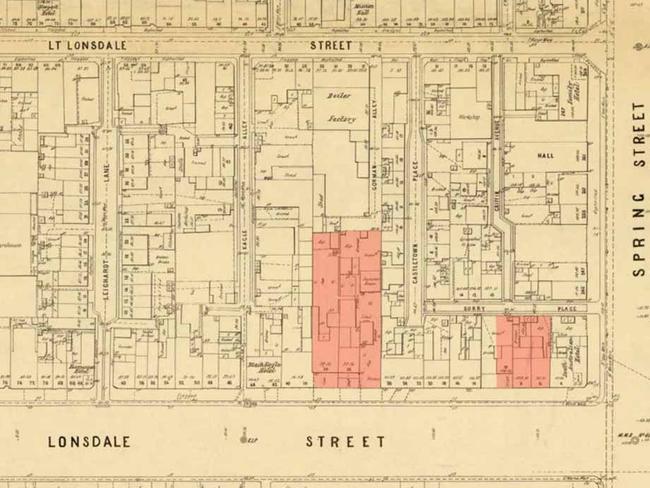

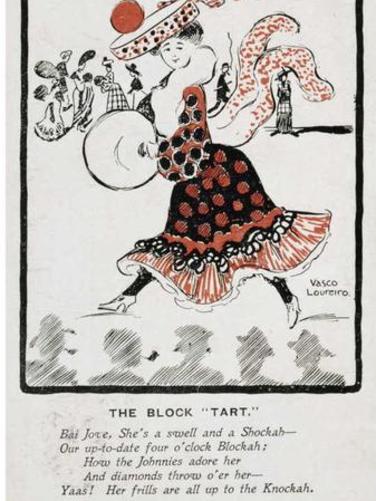

The area surrounding 50 Lonsdale Street — or Little Lon as it was known — was dubbed a red light district and the conservative media painted it as a debaucherous place — with Madame Brussels, in many cases, the scapegoat for all unsavoury behaviour in the area.

This is the story of one of Melbourne’s most notorious, but equally brilliant women, Caroline Hodgson, or Caroline Pohl after her second marriage.

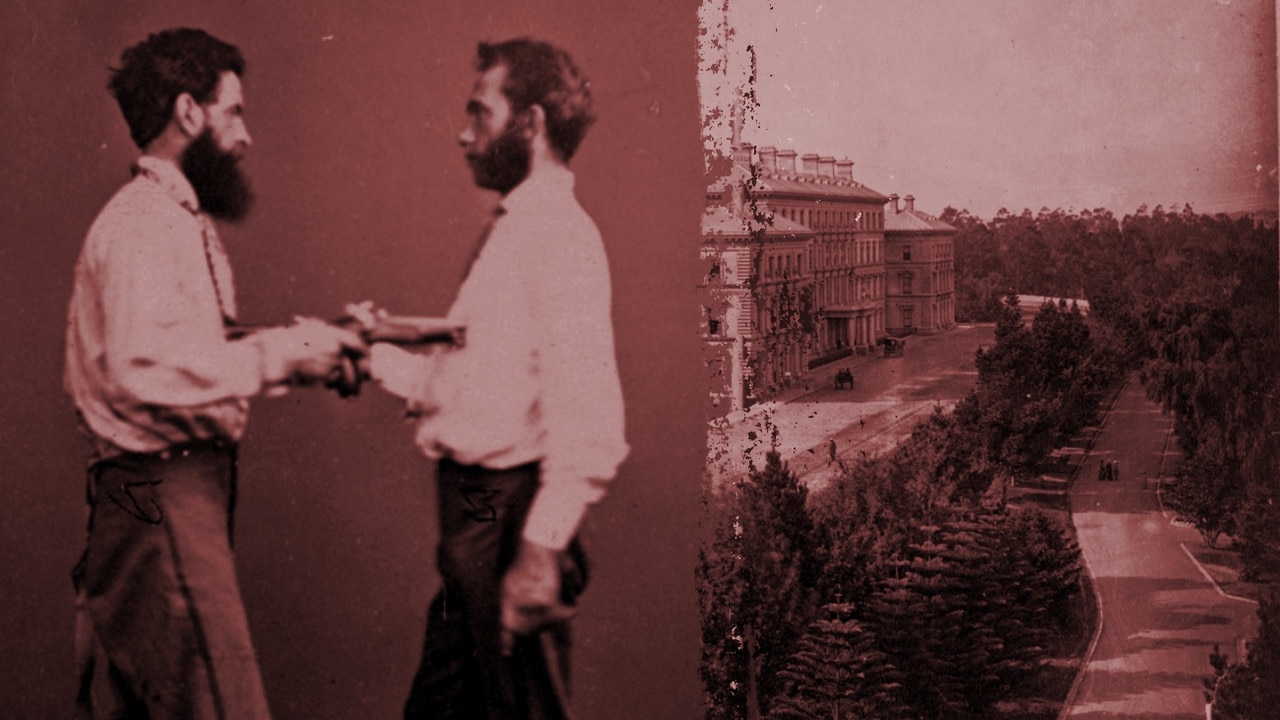

Caroline Hodgson was born in Prussia in 1851, and at age 20, married Studholme George Hodgson, the eldest son of a wealthy Hampshire landowner.

The couple then departed for Melbourne, arriving in July 1871, and Studholme joined the police force and was sent to Mansfield in regional Victoria 17-months later, leaving his 24-year-old wife to fend for herself in the big city.

At the time, the only jobs for women were as housekeepers or seamstresses, which had low pay and generally terrible conditions.

THE MASSACRE IN THE BOTANIC GARDENS

The only lucrative industry that women could make a decent buck was prostitution — which wasn’t illegal in 19th century Victoria per se.

By the end of 1874, Madame Brussels opened her first brothel by leasing a property at 8 Lonsdale Street.

Soon business was booming, and by 1877 she was in a position to purchase a seven-room brick house at 32 Lonsdale Street — right on the corner of where Madame Brussels Lane is today.

In the essay Making Melbourne Marvellous, John Leckey said Brussels “was always well-dressed, drove in a smart carriage, and educated her daughter at a respectable private school while they resided at 39 Beaconsfield Parade, St Kilda.”

In 1878, local policeman, Sergeant Dalton, was quoted in a report saying that Madame Brussels weekly earnings were “something enormous like 3 or 4 pounds” and that “no other brothels were as extensive”.

By 1885 she had bought an adjoining six-room house and joined the two buildings together, making Melbourne’s first super brothel..

No less than eight brothels in the area were controlled by her at some stage — most were high class and opulent, but others like 4 Casselden Place were more dubious, catering to a less gentlemanly client.

EARLY MELBOURNE SITES THAT SHAPED OUR CITY

It’s alleged that Brussels had financial support of lawyer, politician and one time Melbourne lord mayor — Samuel Gillott.

Gillot is also said to have been Madame Brussels link to the upper crust in Melbourne — introducing her to politicians, prominent businessmen and military officers.

The rise of Madame Brussels was rapid and soon there were many rumours circulating — mainly instigated by the moral crusaders who chose her as the representative of an industry they were determined to shut down.

The papers regularly reported on her business dealings and court appearances, but none more than the Truth newspaper, which followed her every move and reported on every salacious rumour.

The paper labelled her as the “the worst and wickedest woman in Melbourne”, a “hellish harridan”, and a “morally putrescent prostitute’s pimp”.

The Truth linked Gillot to Brussels and he resigned from parliament after the article hit the newsstands — a clear message from the puritans that liaising with the Madame certainly had its risks.

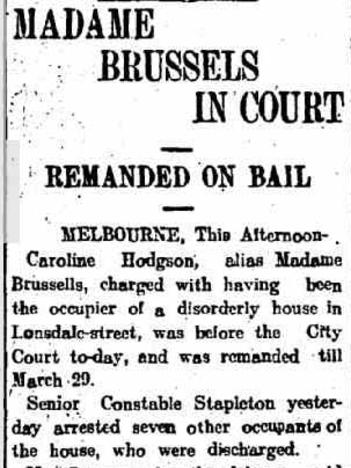

She was frequently hauled before the court — probably in response to the reportage in the press — as, let’s face it, the police and lawyers would most likely have frequented her bordello.

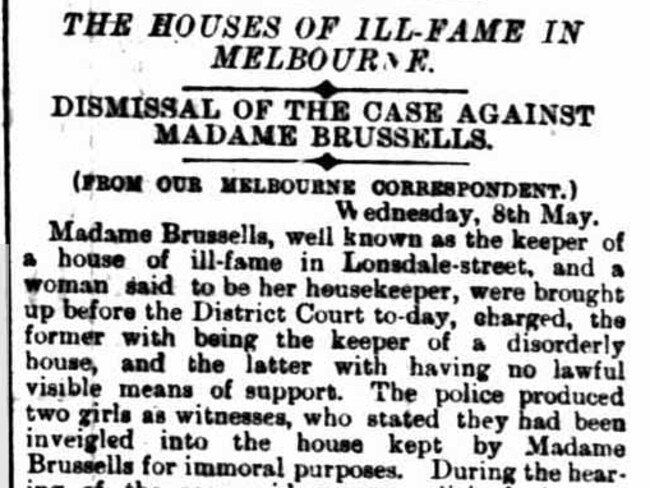

In May 1889, crowds flocked to the District Court to see Madame Brussels called before the magistrate — but she was found not guilty of procurement, and the court said that her house was well-conducted.

Later police prosecutions were also unsuccessful and in August 1898, Madame and her Lonsdale Street neighbours, Maude Miller and May Baker, were tried for occupying premises frequented by persons without lawful means of support.

Again police witnesses agreed that the houses were well conducted, and the chief magistrate dismissed the charges.

Behind all the scandal, Madame Brussels personal life was a rather sad affair. Her first husband, Studholme George Hodgson, became ill with tuberculosis in late 1892, and Brussels arranged for him to be nursed at a property she owned on Beaconsfield Parade, St Kilda until he died in 1893.

She then married engineer Jacob Pohl at St Patrick’s Cathedral in 1895 — she was 44 and he was 27. They lived at 32 Lonsdale Street for 10 months before travelling to Germany for a holiday, where Pohl deserted her and went to South Africa.

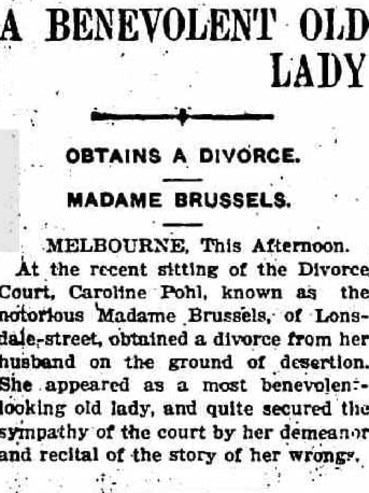

She returned to Melbourne alone and was eventually granted a divorce in 1906, ‘on the grounds of desertion’.

The papers reported on the divorce, saying Brussels: “Appeared the most benevolent looking old lady and quite secured the sympathy of the court”.

The same year she was hauled before the courts again — and let go one last time. The legal system was certainly on her side, perhaps fearing reprisals if she was ever convicted.

The moral crusaders failed to bring Brussels down, and in the end it was ill health that would claim her life. She died from diabetes and chronic pancreatitis in Lonsdale Street in 1908 and is buried at St Kilda Cemetery beside her first husband. She was 57.

The Madame could never have imagined that Melbourne City Council would name a laneway after her and that punters would be drinking in a bar that bears her name.

The bar is perhaps the most fitting tribute to the woman — who would be right at home sipping champagne on it’s gorgeous outdoor deck.

Madame Brussel’s brothels at numbers 6-8 and 32-36 Lonsdale Street were demolished to make way for factories sometime before 1914, and these were demolished to make way for the Commonwealth building in the 1990s.

Major archaeological investigations were conducted in the “Little Lon” block in 1988-9 and 2003, and all of the artefacts recovered during these digs are held by the Melbourne Museum — including bottles, coins and items from everyday life in the 1800s.