McGuire at 50: How a boy from Broady became Eddie Everywhere

EDDIE AT 50: HOW a boy from Broady became Eddie Everywhere - and what he found out about life along the way - through the eyes of ANDREW RULE.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE first time I saw the kid, he was hunched over a scarred wooden bench in the old Windy Hill press box. He had a grubby telephone jammed to his ear, a pen and a pile of dog-eared papers, and a look of such fierce concentration you’d think he was playing chess, not watching local cricket.

He was a long way short of his first shave or a driver’s licence and had obviously ridden to the ground on the bike leaning on the steps outside. But here he was, dictating copy like an old pro.

When he finished filing his story, he looked around and answered the unasked question. “I’m Frank McGuire’s brother,” he said. “Eddie.”

21 MUST-SEE FOOTY SHOW MOMENTS

EDDIE FUMING OVER PLAN TO 'REWRITE FOOTY HISTORY'

It was summer in late 1980. Eddie McGuire was barely 16 but well on the way to being a sharp sports reporter and plenty more besides.

That afternoon he was covering District Cricket for Australian Associated Press. When he went to a media awards night a few weeks later in his older brother’s suit, the agency people were astonished to find their star recruit was a schoolboy in disguise. They didn’t hold it against him, and let him cover an international match at the MCG “sitting next to Henry Blofeld and Peter McFarline,” world-renowned cricket writers who afterwards took him to the Long Room for an illicit beer: a young warrior’s initiation by tribal elders.

At that stage he’d already put in three seasons doing footy “stats” for the old evening Herald’s Saturday edition. His brother Frank, a gun state political reporter, worked an extra shift filing VFL football on Saturdays for the extra money.

It was Frank who’d first smuggled in Eddie as his “stats man” — never mind that he would rush straight from playing footy for his school team and turn up with muddy knees hidden under long pants.

“The other journos would wonder why they could smell liniment,” Eddie recalls, laughing.

Frank would file deadline copy furiously at the end of the game while Eddie sprinted to the rooms to get the umpires’ reports and news of injuries from players and officials who didn’t mind giving the chirpy kid a leg up.

“Between us we’d napalm the game,” says McGuire. “We had a scorched earth policy.” Frank coached him to watch the wise “lone wolf” reporters and never to stand with the pack.

Working weekends was tricky. One Saturday, Eddie persuaded another reporter to take notes for him at a cricket match at the old North Melbourne ground while his father drove him to Aberfeldie to run in the 800 metre race at the inter-school sports, then drive back to Arden Street to grab the crib notes and file his story.

The McGuire boys were always hungry for work. Three and a half decades later, Eddie still is. If anything defines the driven man the cynics dubbed “Eddie Everywhere”, this is it. He doesn’t rest.

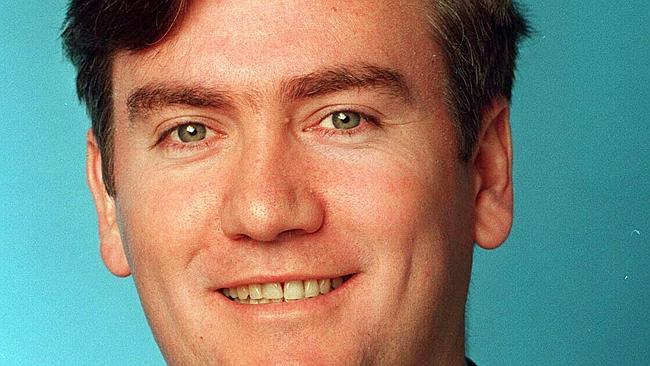

The tough, twitchy kid who pedalled his pushbike from Broadmeadows to Essendon to cover cricket is turning 50 next week. Recalling that far-off afternoon, he reveals a glimpse of the incandescent ambition that turned a hyperactive schoolboy into a one-man media phenomenon.

“At least you know I did the work”, he says. “I wasn’t out surfing like the rest.” He laughs but he’s not joking.

That’s Eddie. Cheek and charm on the surface, adrenalin and anxiety underneath. A friend of his says he’s “the most unknown known person I know.”

WHEN the Channel Nine television program This Is Your Life did a segment on McGuire a few years ago, he was asked to name his heroes. He listed Muhammad Ali, the great Collingwood full forward Peter McKenna — and his brother Frank McGuire.

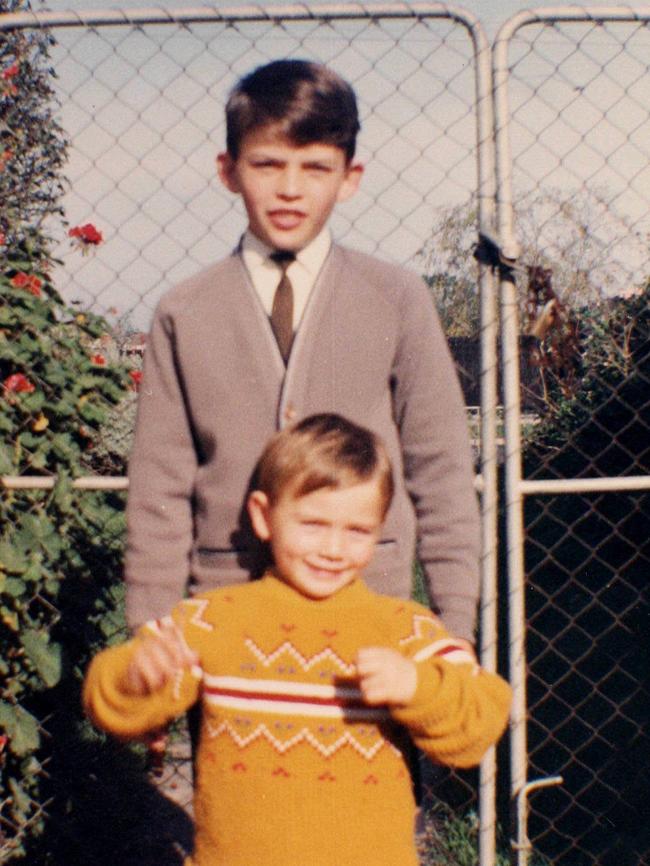

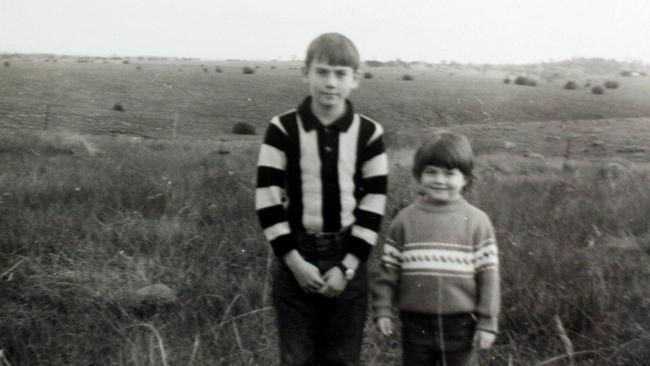

It might sound calculated, like a politician playing the family card. But those who knew the McGuires as youngsters know how close the brothers were despite — or because of — the fact they were born seven years apart.

“Dad said to me when Ed was little, ‘Your duty is to take care of your brother’,” recalls Frank, eyes lit with affection as he speaks of their parents.

He is standing in the middle of his Broadmeadows electorate office, a shop front opposite the new City of Hume building next door to the Global Learning Village. Edward McGuire senior’s old hat hangs permanently on the back of the office door as a tribute. His best hat (and suit) were buried with the old man three years ago. He was 94.

The State Member for Broadmeadows is smaller than his baby brother and seems in some ways gentler. It’s as if he spent his formative years toning down the Broady effect whereas Eddie kept it on high rotation. Maybe it’s a sign they were born in different decades: Frank in Glasgow in 1957 the year before his parents (and big sister Evelyn) crossed the world to build a new life, whereas Eddie and Brigette were born in Melbourne in the 1960s.

When Frank got 14-year-old Ed the Saturday footy “stats” job with The Herald it might have seemed like hard work for a kid but the McGuires knew it wasn’t, really. Compared with what their parents had endured to get them there, reporting was light entertainment.

At 13, at the height of the Depression, their father had gone to work leading a pit pony in the coal mines “a mile underground” near Glasgow. Their mother Bridie Brennan had escaped a damp Irish cottage full of younger brothers, promising herself that the poor farmer’s daughter would not be a poor farmer’s wife.

Bridie took a cheap berth on the “cattle boat” taking stock to market to England. She later met and married Edward McGuire, by then a war veteran. They met at a Butlin’s Holiday Camp but not on holiday: she was a waitress; he was a toolmaker doing maintenance.

They were an intelligent pair determined to escape the poverty and bigotry of Britain in the 1950s to give their children a chance. They dreamt of Australia’s “wide blue sky” and scraped up the ten pounds to sail on the Castel Felice in 1958.

The week after they disembarked in Port Melbourne, Edward landed a job with the “Board of Works” and stuck to it the rest of his working life, although he also held down part-time jobs as well.

A year to the day after leaving Southampton, the McGuires moved into a raw new Housing Commission house on the windswept paddocks at the end of the Broadmeadows line and stayed there: a beach head in the new world.

With “a job, a house and the sun on your back”, Edward McGuire told his children, he felt blessed. He joked he was never homesick because Broadmeadows had “so many scotch thistles”.

“They were the grateful generation,” muses Frank. All they wanted was their children to get the education they’d missed themselves. Bridie worked afternoon shifts at the local factories — Yakka, Ericsson and Nabisco — and got home long after her kids were in bed.

First Frank, and later Eddie, would run home from St Dominic’s primary school at lunchtime to eat with their mother before she left for the factory. It was good training: both excelled at school athletics and football.

Frank says of Bridie: “She had great emotional intelligence before that phrase was even coined. Dad was gregarious, like Eddie, but Mum was our first great educator.”

Bridie taught the children to read aloud before they went to school and the nuns did the rest. Eddie recalls her making him “read with expression”. Big sister Evelyn took after Bridie and would herself become a successful teacher.

The brothers boast that their younger sister Brigette, reporter turned sports marketer, was an ace tennis player and has passed on the competitive McGuire genes to her sons, both promising players.

Frank and Eddie shared a bedroom until Frank left home. In it they hatched dreams of brilliant careers and quizzed each other on sports trivia. They thought that newspapers and playing football would be their passport to the world.

On Frank’s 11th birthday in 1969 he starred in the St Dominic’s footy team the first time it won the local premiership.

Eddie was not yet 5 but knew the game from endless backyard kick-to-kicks. When Frank kicked the winning goal, his seventh of the day, his little brother triumphantly signalled the score before the goal umpire reached for the flags.

Frank was chaired off the Jacana Reserve (“That was our field of dreams, then”) and Eddie never forgot the moment. “He loved it and soaked it up,” says Frank.

Frank “blazed the trail” for Eddie at school in running and football and scholastic achievement. When he won a scholarship to Christian Brothers College, St Kilda, it set the bar.

When Eddie was in Grade 5, trouble hit. Their mother fell ill and couldn’t work. She told Eddie if he couldn’t win the scholarship he wouldn’t be following Frank to the college. Underneath their pride and stoicism, Mr and Mrs McGuire were scared of being retrenched. He sensed their fear and never forgot it.

A suddenly serious McGuire, aged 49 and 11 months, sits up in his chair as he tells the story of how his 10-year-old self had coped.

He was no model student at St Dominic’s but he decided to confide in a stern nun, Sister Matthew. She proved to be the Kevin Sheedy of nuns. For months, before and after class, she coached him, pushing him through every old scholarship exam and set text until he felt like a quiz-show star.

When the big day came, he got through the scholarship paper so fast he thought he must have missed a page. He hadn’t but it still worried him.

A few weeks later he came home from school at lunchtime and his mother was standing at the letter box. “I can remember the shiver going up my back,” he says. “She opened the letter. I’d won the scholarship. I floated back to school, walking on air. I knew I’d been given a golden ticket to life.”

The middle aged Toorak mini-mogul is not actually crying as he says this. But his eyes are suspiciously bright.

It’s Bridie he’s thinking about, not Broady.

SUCCESS has many fathers. Several can claim to have spotted young McGuire’s potential when he went job-hunting in his last year of school in 1982. The Herald wasn’t taking anyone straight from school that year. The Age offered him a cadetship — but not until the following July, nine months later. So he applied to country and suburban newspapers, just in case.

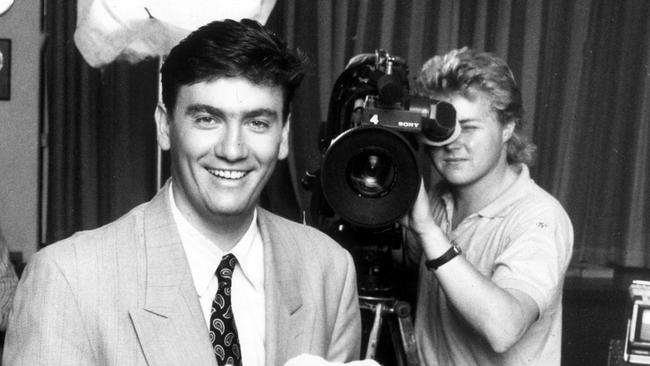

Channel 10’s long-time news reader David Johnston let him work on weekends while he was still studying for his Year 12 exams.

His attempts at an audition “stand up” report have become part of local television mythology — the grainy black and white tape wheeled out at every newsroom reunion. In it, the Broady boy scowls and swears every time he fluffs the take.

But the station’s sports editor Tony Banks saw something in him: the fact he’d already done so much work covering footy and cricket implied he was a natural-born news hound.

It wasn’t until McGuire agreed to start work with the Macedon Ranges Telegraph at Gisborne that Ten put him on full time. McGuire made his own luck, writing a letter to Ten to say it was going to lose him to the tiny newspaper if it didn’t sign him.

He wrote only two stories for the bemused Macedon Ranges editor. The first was to introduce himself to readers. The next was the exclusive that he had been “poached” by Channel 10.

Within days he was covering VFL football. He met the game’s legends, from Whitten, Dyer, Lou Richards and Neil Roberts. One night Drew Morphett introduced him to Sam Newman.

“They took me to a restaurant in Toorak Road. I’ve got Dad’s car out the front and $10 in my pocket. I’m terrified of what it would cost, and relieved to get the pepper steak for $7. The most exotic food I’d had before that was mum’s Irish stew.”

Afterwards they took him across the road to Silver’s nightclub, where he learned about drink cards from Newman the nightclub king. It was the start of a riotous decade of working and playing hard. Both Tony Banks and David Johnston suggest he came close to being sacked for turning up after all-night sessions and going to sleep at his desk. But he kept breaking stories and that saved him.

The first time McGuire got to read the sports news on television, his parents took photographs of the screen at home. After the bulletin he called his mother and said: “Thanks for teaching me to ‘read with expression’, mum.”

McGuire remembers Tony Banks and “DJ” fondly but it was Ian “Jonno” Johnson, then Channel 9 supremo, who gave him a break that turned into the ride of his life.

Johnson arranged to meet him at a Toorak Road cafe to negotiate. He saw McGuire drive past several times, trying to park outside the door to show off his borrowed Mazda convertible. When he came in, he suggested that the car came with his job at Ten, which didn’t fool Johnson.

He was promised the job but wanted proof of the deal. Johnson scrawled “You’re in” on a beer coaster and signed it, setting up one of the biggest television careers since Graham Kennedy.

Johnson had an idea for a football-themed show — a brilliantly simple hybrid of the old “league teams” shows and the traditional “tuxedo” variety shows that had flourished with Kennedy, Bert Newton and Don Lane. He wanted McGuire to host it “because he’s a natural.” McGuire brought in his old mate Sam Newman, Trevor Marmalade and a rolling cast of footballers and Nine had a 20-year-hit.

McGuire kept chasing the hard ball. In 1998 (by then recently married to Carla Galloway) he took over as president of Collingwood Football Club. Rob Sitch, key writer and performer with the tight-knit crew featuring Santo Cilauro, Tom Gleisner and others, had recruited the young McGuire to do sports reports on their FM radio show in the late 1980s.

Sitch recalls McGuire confiding afterwards that in his moment of triumph, leading singing of the Magpies theme song to a standing ovation, he had “never felt so lonely in my life”. He knew the backslappers would kick him to death if he couldn’t turn the club around. “It was down to him now.”

Collingwood was in the red and winning wooden spoons. By 2002, it was making money and wrestling the Brisbane Lions for the flag. In the dying moments of a gut-busting Grand Final that the young Magpies couldn’t quite nail, McGuire’s face was a study of controlled anguish. Afterwards, he told Sitch wistfully what he’d been hoping: “While we were still a chance I was thinking about my dad getting to hold up the Cup.”

In late 2005 he left the Footy Show to “have a crack” at being chief executive of the Nine network in Sydney in 2006. He got there just in time to be asked to make a heap of jobs redundant, and was vilified for it. By mid-2007 he was back in Melbourne, leading Collingwood towards the promised premiership, and taking on as much work as he could.

Anyone else with a family — he and Carla have two sons — might be happy to support one full-time radio gig, or to host a quiz show, or to run a media production company and a portfolio of real estate, art and other investments. Eddie does the lot, and more. Too much is never enough.

Last month, Carla sent out an email to dozens of her husband’s friends asking them to contribute favourite quotations to gather into a book for his 50th birthday this week. The surprise was spoilt when it leaked to a gossip columnist but the thought counts. Maybe the saying that best sums up McGuire is “If you want something done, ask a busy man.”

A woman who doesn’t know McGuire tells a story about when her sons were at his old school, CBC St Kilda, in the 1990s. The school parents needed a “drawcard” old boy to host a fund raiser. A certain television star with few commitments demanded $5000 to “perform”. But McGuire said “No worries” and somehow fitted it in to his crazy schedule. “He’s all right,” says the mother, a hard marker.

On the morning he fits the Herald Sun into his timetable, McGuire has just come from a late breakfast meeting after finishing his radio show. You’d expect it to be AFL or television or radio or real estate business. Wrong. He’d been meeting Brendan Nottle, the Salvation Army major who spends long nights on the streets with other “Salvos” helping the hungry and the homeless.

McGuire had found out Nottle hadn’t had a family holiday in years and organised one, courtesy of Collingwood. He says Nottle was “belted” by an ice addict recently. He worries that Nottle will be burned out by the bad things his people confront after dark, week after week.

“The ice situation is unbelievable,” he says. “Good people are now breaking.” But, unlike some self-made men, he doesn’t beat up those who haven’t succeeded the way he has. “People have to drop this idea they deserve everything for nothing,” he says, “but we’ve got to get over this talkback cliche of ‘bludgers’ and ‘losers’. The fact is, 20 per cent of the population need help and it’s up to the rest of us to help them.”

He might be a multi-millionaire now (“I can’t pronounce ‘millionaire’ — but I am one”) but he has the same frown as that kid at Windy Hill 34 years ago. Things to do, deadlines to meet.

Disclaimer: Andrew Rule contributes to McGuire’s Triple M breakfast radio program.

andrew.rule@news.com.au