Mad Max stands the test of time on the 40th anniversary of its cinematic release

Shot on the smell of an oily rag, Mad Max burned rubber and grossed $100 million. How did a budget Aussie film, released 40 years ago this week, become a worldwide smash?

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Max Rockatansky, who swaggered into frame 40 years ago this week, casts a mighty long shadow across the cultural and cinematic landscape.

“Action cinema owes a huge debt to George Miller and Mad Max,” media and cultural studies expert Professor Tom O’Regan says.

The academic, who first saw Miller’s dystopian demolition derby at a rundown cinema in a seedy part of Brisbane, describes it as a “revelation”.

BEST FILMS TO TAKE YOUR KIDS TO SEE

BOREDOM NOT AN OPTION FOR SHAZAM

CAN DUMBO PLEASE DISNEY PURISTS?

“This was a remarkable film; it was so visceral and scary. And it didn’t let off. There was no point at which it wasn’t going to top what you had just seen.”

Shot in and around Melbourne over 12 weeks, on a budget of less than $400,000, the original 1979 film went on to gross $US100 million at the international box office.

It held the Guinness World Record for most profitable film for almost 20 years (until being finally unseated by The Blair Witch Project).

“Mad Max is one of those films where you can genuinely say Australian film influenced international filmmaking,” Prof O’Regan, based at The University of Queensland, says.

“It was really noticed. People took it up.”

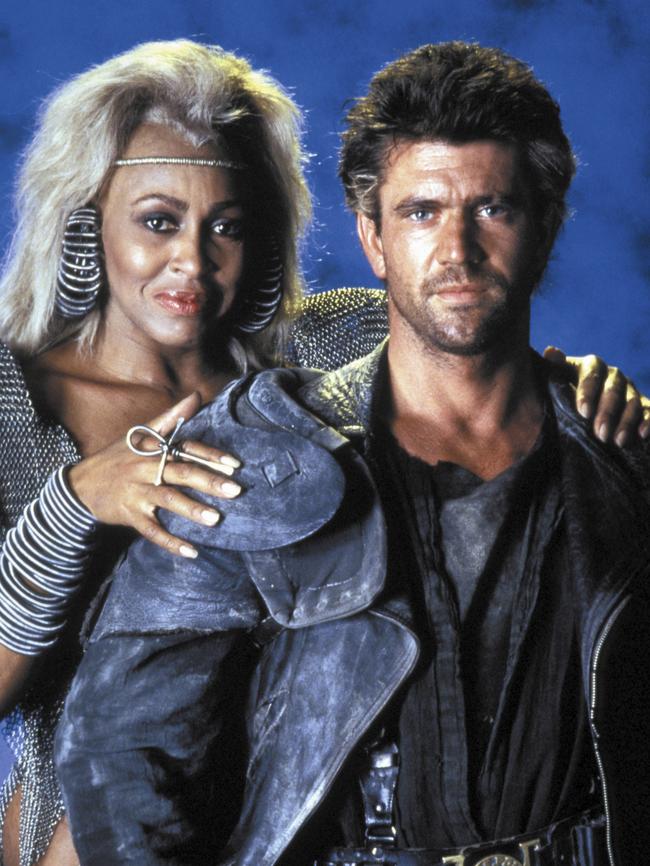

The low-budget B-movie made by a bunch of novices also launched the international career of two-time Oscar winner Mel Gibson, whose character in the hugely successful Lethal Weapon series is clearly an extension of that early screen persona.

According to Gibson, he didn’t intend to audition for Mad Max at all.

An acting student at the National Institute of Dramatic Arts, he was only dropping off his flat mate, Steve Bisley, (who wound up playing Max’s doomed partner, Goose).

As the story goes, Gibson had been beaten to a pulp in a bar fight the previous night and his bruised and battered look captured the attention of the casting agents who were “looking for freaks”.

When he returned, healed up as requested, Gibson’s leading man looks and charisma landed him the lead role.

There is, however, another less colourful version of events in which Miller attended a play that co-starred Gibson and Bisley and was won over by Gibson’s physicality and the pair’s onstage chemistry.

It’s hard to understate Mad Max’s impact on cinema, popular culture and video games in the four decades that followed.

Intense, non-stop, relentless, Miller’s feature film debut and its more polished follow-up, initially released in the US as The Road Warrior, turbocharged the genre.

Guillermo del Torro, David Fincher, James Cameron and video game director Hideo Kojima have all listed Mad Max 2 as one of their favourite films.

“Mad Max, and those that followed in its path, have become part of the world’s monoculture, particularly through games and anime and manga and so on,” says Miller, who 30 years after Beyond Thunderdome, had to re-imagine his own creation for Fury Road, so that it didn’t now feel generic.

Clearly, there was a lot more going on under the bonnet of that black 1973 Ford XB Falcon GT, aka the Pursuit Special, than cultural commentators such as Phillip Adams realised at the time.

In his now infamous critique, entitled “The Dangerous Pornography of Death”, published in The Bulletin on May 1, 1979, the public broadcaster said Mad Max would be “a special favourite of rapists, sadists, child-murderers and incipient Mansons”.

Describing it as “a celebration of everything vicious and degenerate”, he said Miller’s film had “all the moral uplift of Mein Kampf”.

Looking back, Miller has every right to feel vindicated.

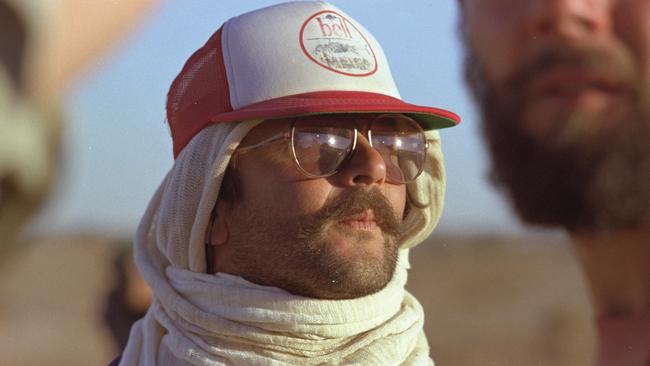

“People thought that (producer) Byron Kennedy and I were slumming making an action movie, but the truth is, it was more than an action movie,” he says.

“I think that’s why, 40 years later, we are still making Mad Max movies. If it had been just a quick exploitation movie, I don’t think we’d be here.”

For Miller, the film was partly an exploration of Australia’s obsession with the V8 engine.

As he put it in a 1979 interview with Cinema Papers, “the USA has its gun culture, we have our car culture”.

“Growing up in remote Australia, the car was the thing — big, big expanses of landscape and long, straight roads,” he said.

Prof O’Regan, who was raised in the central Queensland regional city of Rockhampton, recalls how the road out of town became a drag racing strip between midnight and 3am.

Random Breath Testing had yet to be introduced.

“Before RBT, drinking and driving was regarded as almost as natural as breathing. The culture in every pub was, ‘Let’s have one for the road’. You don’t hear that anymore,” George Paciullo, former NSW MP and an architect of the scheme, says.

The violence, blood and carnage in Mad Max can partly be attributed to Miller’s own experiences in a hospital emergency department.

Before he became a filmmaker, Miller studied medicine. He completed his residency at Sydney’s St Vincent’s Hospital in 1972.

“People were coming into emergency with really bad injuries and that sort of got to me in a way. I think making the first Mad Max was a way of processing that,” he says.

Screenwriter James McCausland also drew heavily on his observations of motorists’ response to the 1973 oil crisis.

“Long queues formed at the stations with petrol — and anyone who tried to sneak ahead in the queue met raw violence,” he says.

The are obvious parallels between Miller’s vigilante-in-a-leather jacket and Sergio Leone’s Man With No Name and Charles Bronson’s Death Wish franchise.

But Miller also looked to comedians such as Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and Mack Sennett for inspiration.

“A syntax was formed, basically by the silent movies, that I loved and that I treated very seriously. To be honest, I have always seen action movies as a kind of pure form of the film language,” Miller says.

That might go some way to explaining why Mad Max has stood the test of time.

“Craggy, explosive, somewhat out-of control, excessive, and arresting” is Prof O’Regan’s verdict now.

“OK, so it wasn’t as technically polished as the second one. It didn’t have its violence under the same stylised control, and that made it a little bit more threatening and nasty,” he says.

Contemporary audiences, however, may well be surprised by the film’s relative lack of graphic violence.

“People imagined violence in that film that wasn’t there. The filmmaking was so powerful that they filled in (some of the more nasty bits),” Prof O’Regan says.

“The filmmakers didn’t have the budget to give you a graphic visualisation of what was going on in certain key scenes.”

For fans, the film is still alive, regularly celebrated with screenings, cosplay events and re-enactments.

In February, more than 1500 dedicated fans flocked to Maryborough in Queensland to mark the 40th anniversary.

“It’s like returning to Mecca,” fan club founder Steve Scholz says of returning to the filming locations.

“The original (film) — for all its flaws — contained some of the most phenomenal car chase scenes ever committed to celluloid.”

Melbourne University film and television lecturer Andrew O’Keefe said the film invented an entirely new genre.

“It became a cultural favourite in Japan before it took off in Australia,” he said.

“George Miller said it tapped into the universal mythology of a universal warrior restoring order.”

He said fans still responded to the original film and its sequel four decades later for a number of reasons.

“It’s cinematic pride because everybody loves cinema but it was also a thumb in the face of proper historical filmmaking,” Mr O’Keefe said.

“It was bold and ballsy and taps into the idea of subcultures.

“Australians love their cars and love to get out there and go wild in them, so there was that.

“But it was also that world cinema had never seen anything like this before.

“This was a western using motorcycles and cars and it was made completely outside the system so it also tapped into the underdog culture.”

He said the film could even be credited for planting a seed for the wildly popular music festivals like Burning Man in the US.

“Maybe people just like to get out in the bush and burn things?” he said.

“Mad Max is that. It’s tribal warriors sitting around a fire place except the fire is a combustible engine inside a V8.”

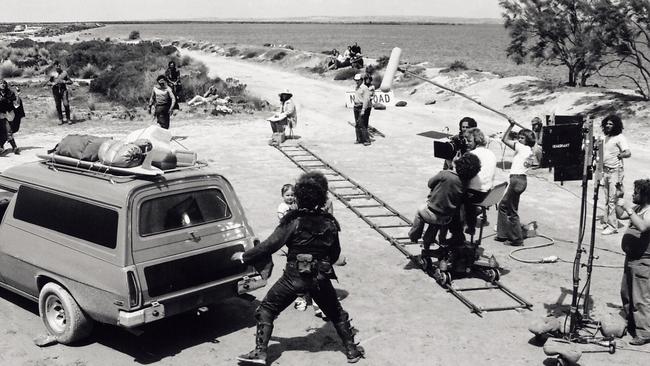

Miller is keen to set the record straight on some of the more apocryphal stories that surround the guerrilla-style nature of the production, which was shot in Melbourne’s backstreets, at Lara and Clunes.

According to local folklore, Mad Max’s set was almost as wild and anarchic as the world depicted within the film and the action sequences often got a little too realistic.

“That’s myth-making,” Miller says firmly. “I mean, having been a doctor, I was obsessed with safety. The fact is we had no injuries to speak of on Mad Max.”

Lead stuntman Grant Page and Rosie Bailey, the actor originally cast as Max’s wife, were, however, injured in a road accident on their way to the set a day before filming was scheduled to begin. Bailey was replaced by Joanne Samuel, causing a two-week delay.

Miller also scotches the myth that he sacrificed his own Mazda Bongo, the blue van seen totalled in the opening chase, for the production.

“We bought an old shell and painted it because I couldn’t afford to wreck my own car,” he says.

Miller and Kennedy did, however, edit the film in the producer’s kitchen, and some of the smaller contractors were paid in slabs of beer.

It’s also true that many of the extras in Toecutter’s crew were recruited from real biker gangs and that Victorian police actively assisted the guerrilla production, once they got wind of it, even though the vehicles weren’t road certified — because they didn’t have mufflers — and crew members illegally used police frequencies for their walkie-talkies.

“If you were pulled up by the police, there was a letter that said: ‘These guys are making a movie, it’s being shot in the outskirts of Melbourne, help them out if they need it’,” Miller explains.

“The cast and crew called them get out of jail free cards.”

Mad Max was released the same year as My Brilliant Career, starring Judy Davis (who graduated from NIDA with Gibson, in 1977),

Although they are very different films, Prof O’Regan sees them as complementary.

“Gillian Armstrong (the film’s director) was a maverick, too. My Brilliant Career is feminist cinema, if you like. OK, it’s a period piece. But (author) Miles Franklin was one of the original women ratbags,” he says.

These “significant, emerging talents” were part of an exciting ’70s New Wave of Australian filmmakers that included Peter Weir, Phil Noyce, Fred Schepisi and Bruce Beresford.

Weir’s critically and commercially successful adaptation of Picnic At Hanging Rock, released in 1975, was one of the first Australian films to reach an international audience.

“Back when we made those first Mad Max films, Australian cinema wasn’t much on the radar,” Miller says.

“In the US, all the voices were dubbed because they couldn’t understand the Australian accent.

“I remember somebody saying to me way back then, ‘You know, before too long we’ll have Australian actors as famous as Steve McQueen’. And I remember nodding my head but thinking, ‘That’s never going to happen’.”

Flash forward 36 years, to the release of Fury Road (2015), the fourth film in Miller’s long-running franchise (two more screenplays — Furiosa and The Wasteland — are waiting to be greenlit).

The story of a decent man and a decent woman (Tom Hardy and Charlize Theron) trying to make sense of a violent, desolate world was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. It won six.

“I have never experienced that type of critical response before,” says Miller, a regular on the Oscars red carpet (Lorenzo’s Oil, Babe and Happy Feet, which took home the golden statuette for Best Animated Feature).

It might have taken a while for the cinematic establishment catch up, but as Miller said right from the very start: Mad Max was never just an action movie.