John Elliott: Corporate cowboy, Carlton president, larrikin and aspiring prime minister

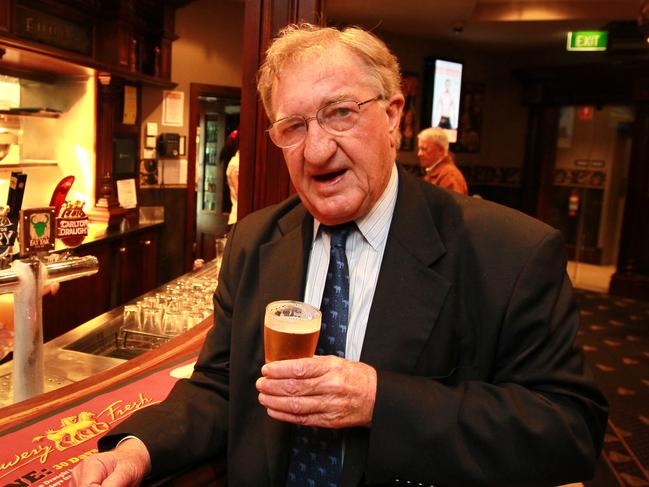

Tributes are pouring in for John Elliott, the colourful and controversial titan of football, business and politics, who died aged 79.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Boardroom buccaneer and former Carlton Football Club president John Elliott has died aged 79.

The Melbourne-born former Elders IXL corporate baron, widely known for taking Foster’s to the world, died at Epworth Hospital on Thursday night.

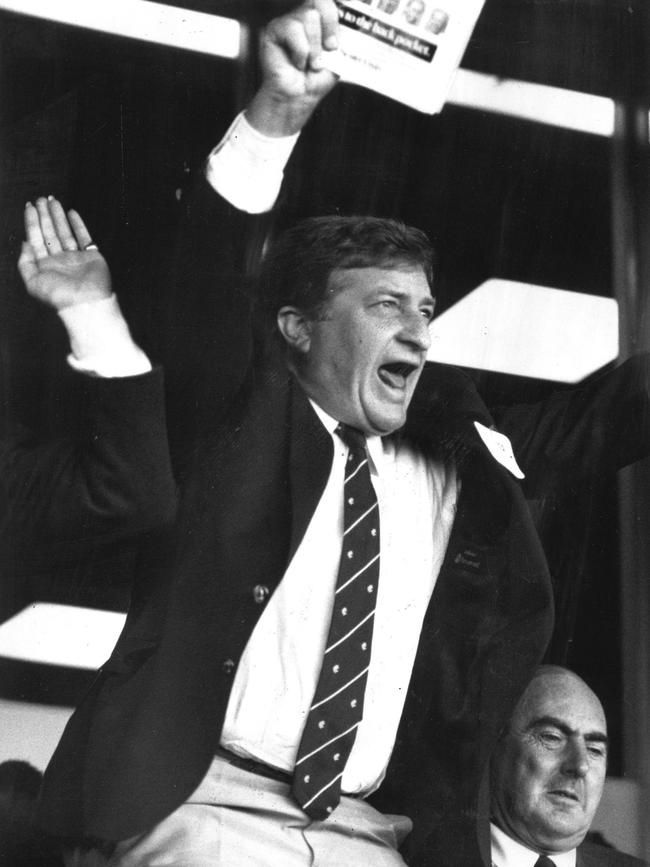

Often caricatured for his larrikin nature, the outspoken Mr Elliott personified the largesse of the ’80s and as a former Liberal Party president, Mr Elliott was also once considered as a potential prime minister.

Elliott’s son, 3AW broadcaster Tom Elliott, confirmed the death on Thursday evening to the Herald Sun.

“It is with great sadness that we announce the death of John Dorman Elliott,” Tom Elliott said.

“He died Thursday evening at the Epworth Hospital in Richmond after a short illness.

“Dad will be greatly missed by his four children, Tom, Caroline, Edward and Alexandra. Their children, Henry, Sebastian, India, Ava, Lottie and Mathilda, will remember forever their “Grandpa Jack”.

“Also in mourning are John’s brother, Ross, sister-in-law Jenny, former partner, Joanne, and second wife, Amanda. They are joined in grief by numerous nieces, nephews, grandchildren and other close relatives. Vale Dad.”

Political, business and football identities have paid tribute to Elliott.

Former Premier Jeff Kennett described his friend as a “larger-than-life character”.

“He lived a very full life,” Mr Kennett said. “He was terribly proactive in terms of the principles of the private sector and he was very supportive of the conservative side of the Liberal side of politics.

“I and many others on our side of politics will be very grateful for the leadership and enthusiasm and advocacy that he showed during the ’80s, ’90s and early part of the 21st century.”

Elliott was “unashamedly proud of Melbourne and Victoria”, according to both state Liberal leader Matthew Guy and federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, also Carlton’s number one ticket holder. “He made things happen and will be sorely missed,” Mr Guy said.

On the opposite side of politics, Labor minister Martin Pakula said that, despite his differences with Elliott, he “liked him a lot”.

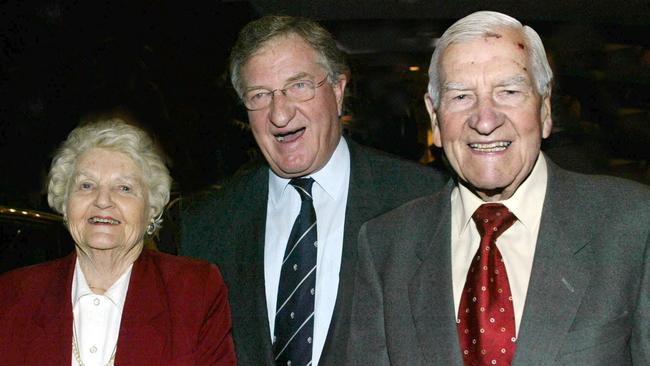

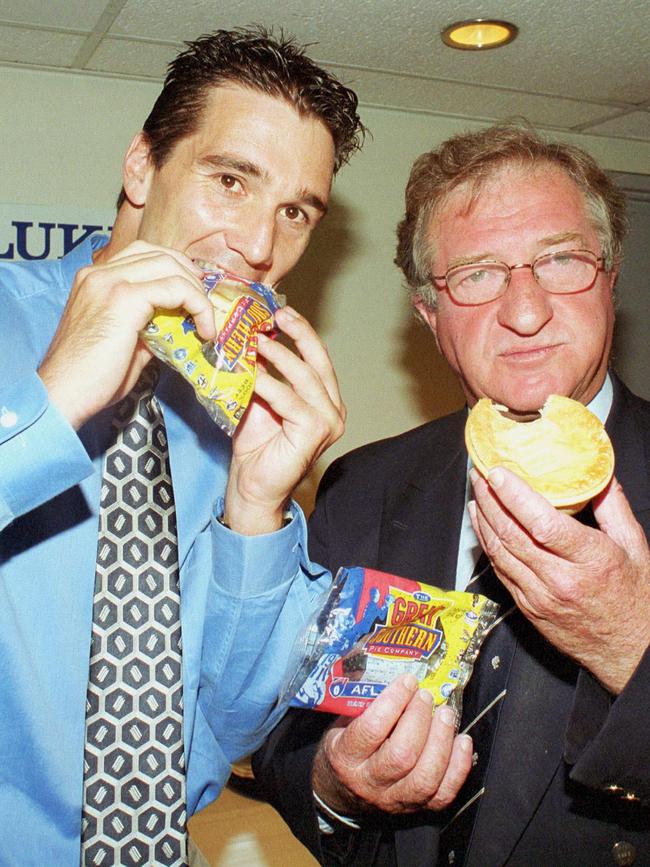

Carlton premiership star Anthony Koutoufides said Elliott was an “amazing man”.

“He led the club so incredibly well, and just created this family environment I’ll never forget,” he said.

“He stood outside (the Carlton clubrooms) having a cigarette with supporters, my mum and dad adored him … he was just a wonderful gentleman.”

Carlton great Greg Williams spoke fondly of the high expectations Elliott set for his beloved football club.

“He wouldn’t come down to the rooms after a game unless we won,” Williams said.

“He expected us to win, and we won often.

“It’s hard to explain, but he was such a great leader … he did it his way – he had his focus on Carlton.”

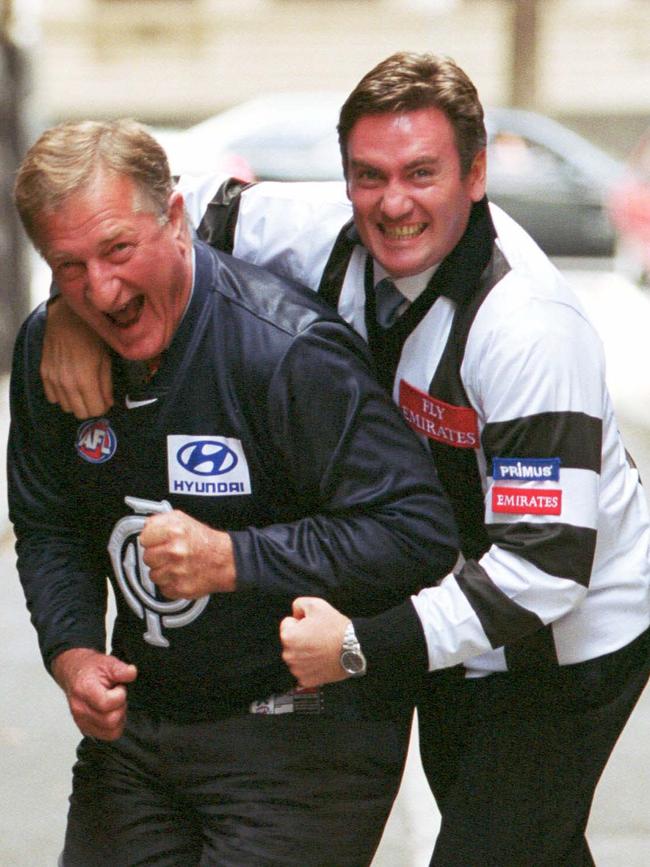

Luke Sayers, who was last month appointed Carlton president, said he would raise a toast to “a man who loved this club”.

“Whilst much has been said and written about the end of John’s presidency, tonight is a time to remember the many achievements during his time at the club,” Mr Sayers said on Thursday night.

“The return of Walls and Parkin, and the premierships they subsequently won; the recruitment of Kernahan and Bradley and Williams; the pride in the jumper and the love of Princes Park.

“John remained a passionate Carlton man, right throughout his life.

“He never stopped wanting to see the Old Dark Navy Blues succeed.”

Kernahan revealed his shock at the larger-than-life former Blues president’s death.

“I loved John Elliott, because he started coming over to the Elders boardroom in Adelaide when I was a kid trying to get me across to Carlton,” Kernahan told SEN radio.

“We go back a long way and John was very good to my family, and myself and we’ve been close mates ever since.

“I had some great long lunches in his boardroom over the years and enjoyed them all the time.

“While he upset a few, had cigarettes where he shouldn’t have, he always remained true to what he was. He was a great man to all of us.”

Kernahan praised Elliott as a “charming” and “very smart” man, who was also an ex-Liberal Party president and successful businessman.

“We’ll miss what John was in those days and we all think very fondly of him today – let me tell you,” he said.

“He was a really powerful man. He did polarise a few along the way and I don’t think that worried him one little bit.

“He was Carlton through and through until the end.”

Three-time Carlton premiership coach David Parkin broke the news to Kernahan.

“We’d been trying to catch up all through Covid. I used to catch up with John all the time for lunch,” Kernahan said.

“Even after his stroke a number of years ago, he was still in good fettle and obviously recently he was in bad health.

“I thought John could go forever. It shocked us all last night.”

A LIFE OF COLOUR

They’ve been writing obituaries for John Elliott – the corporate cowboy, larrikin, footy club president, bankrupt and once aspiring prime minister – for decades.

In the end, old age and a fall may have succeeded where the knockers could not.

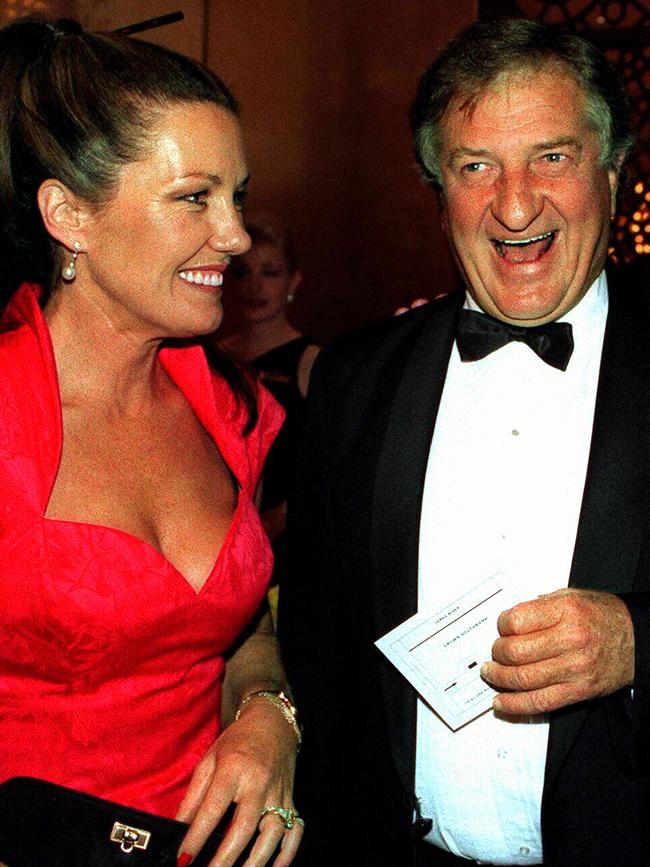

Elliott always outraged and offended, as if he accepted that outlandishness was expected of him. Even in his latter years, he was hard to ignore when he sat at the next table or shuffled down the street after a longer lunch.

This shrunken version of his former might undercut the sweep and bombast of a boardroom buccaneer who eyed off Canberra, and Australia’s biggest companies, with an unapologetic self belief-often described as arrogance.

Elliott, who died at the age of 79, was a relic of another time. He didn’t say “pig’s arse”, as he was parodied, but his aura of casual contempt could explain the assumption that he had.

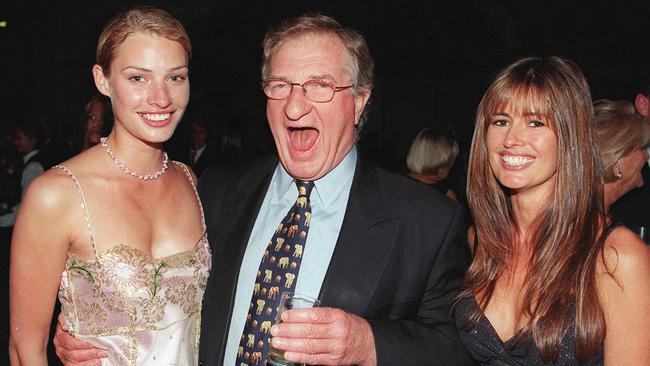

Elliott swilled red wine and pinched bottoms. He was imbued with a prehistoric air of entitlement and a desire for a laugh. The Australian antihero, it was once said, Elliott was admired and abhorred for his “greed is great” persona.

Yet he was a complicated study, a thesaurus’ best friend. He bludgeoned, bullied and brutalised as an engine of many parts who always strived for another deal and another buck.

THE GREAT SURVIVOR

Charming and crass, considered and condescending, Elliott rose and fell, over and over, a kind of conqueror doomed to be defeated. Dated but undimmed, this great survivor outlived the defining figures of a generation who built empires of debt and traded big businesses on a hunch and a whim.

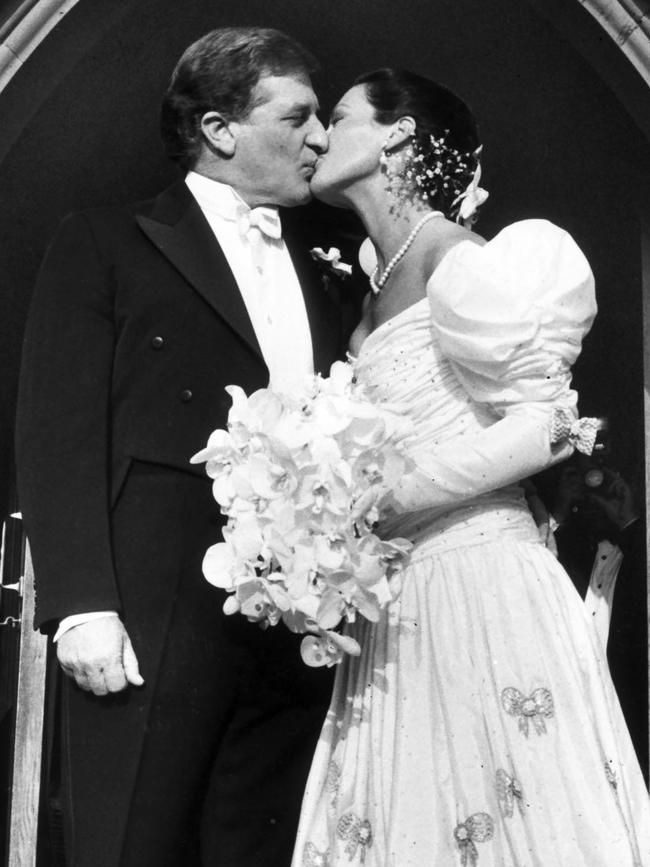

Elliott made up the rules as he saw fit. He didn’t care for the rule-makers. Bankrupted, investigated, twice divorced, Elliott never bowed to opprobrium.

A “belligerent, unlovely testament to the power of positive thinking”, as he was once described, Elliott’s self-belief shielded him from the barbs. Self-pity was not among his failings.

Take 2002. After 19 years as Carlton president, through two flags and five grand final appearances, Elliott had embodied the indomitable disregard of a football club which had enraged opposition fans for generations.

He had endangered reputations, and the odd AFL chief executive, with sweeping critiques of the game and its problems. He had seemed bigger and louder than any other off-field football personality.

When he was finally deposed as Carlton president, after the club was penalised for cheating on salary caps with under-the-table payments, the club he had loved was no longer grateful for his service.

At the time he was separated from his second wife, living in a rented apartment, and was still being pursued by corporate regulators.

His name was removed from a grandstand. The Yorta Yorta people had placed a curse on him after he called Aborigines “unimportant” and “backward”.

A pattern was being repeated. Whenever Elliott soared, he later soured. Elliott had been excommunicated, as he had been years earlier by the Melbourne establishment.

BIG, BOLD AND WITHOUT WEAKNESS

There was a charmed privilege to the breaks offered the son of Frank, who went to Carey Baptist Grammar School, attended Melbourne University and got a master’s degree in business administration on a BHP scholarship.

Elliott attracted a sponsor, Sir Roderick Carnegie, who ran McKinsey and Co, where a young Elliott would learn the tricks of company takeovers and corporate combat.

Elliott wasn’t particularly brilliant. His six-year-old brush with an often fatal bone marrow infection in his heel grew to be a foundation story. Elliott had no weaknesses. He was no Achilles.

“One doctor told me I wouldn’t be able to walk and I walked,” he told a biographer.

“He said I wouldn’t be able to play football, and I played football. Then he said I wouldn’t be able to kick with my left foot and I did that.”

A friendship with BHP chairman Sir Ian McLennan presented Elliott with membership in the Melbourne establishment, and propelled his first major thrust into the corporate hemisphere – the 1972 takeover of Tasmanian jam maker, IXL, which provided a launch pad for the bigger and bolder seizures ahead.

Elliott had listed 300 companies for takeover. He used contacts through McLennan to gather loans, or “seed money” for the takeover.

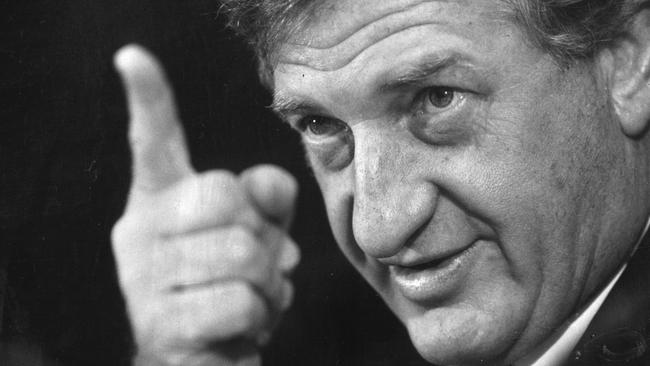

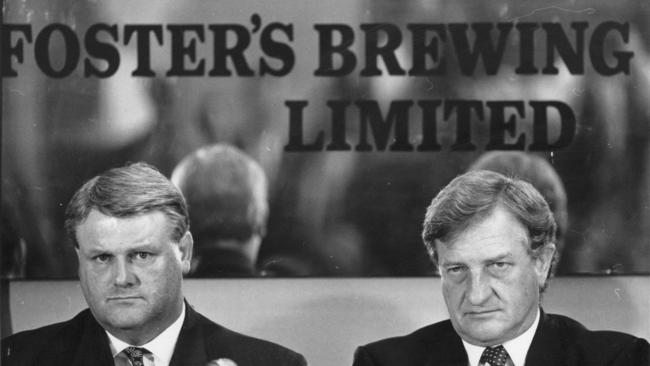

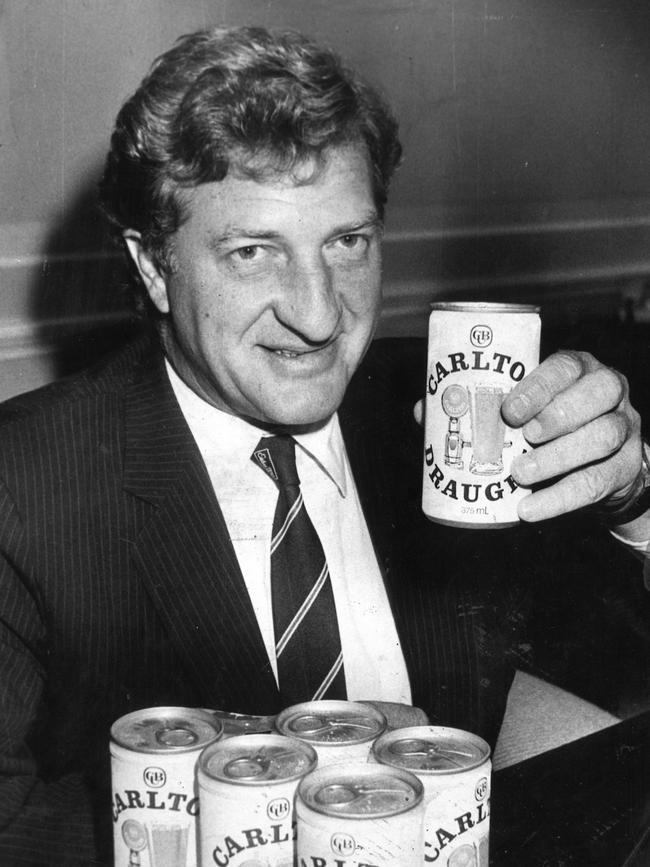

As the 1980s began, the thirty-something life force snared a pastoral house, Elders, then took over Carlton and United Breweries and engulfed a British brewery, Courage. This was the time when he spoke of “Fosterising” the world.

He was likened to an imperious ruler on a Roman coin. “The face of a bruiser with a broken nose gained as a centurion … before he became emperor” was bludgeoned by playing football for Old Carey until he was 35.

As journalist Craig McGregor, who shadowed Elliott for a week in 1987 observed: “A typical gesture of Elliott’s is to lean back in his chair and run both hands through his hair in a gesture as egotistical and coquettish as a male Marilyn Monroe”.

Elliott liked French wine and meat pies, sometimes at the same time. He listened to Winston Churchill speeches for motivation. He never went on holidays; work was a holiday.

His approach was simple enough: crash through or crash. He took stairs two at a time and strode so purposefully that some lackeys had to run to keep up.

BIG JACK’S PLAY FOR PM

His nickname was Thug, or Egg, or King John. He collected ornamental elephants for luck and boasted dozens of elephant ties. When he rescued companies, he swallowed them.

His distasteful stylings were put aside in 1987 when he saved the Big Australian, BHP, from the chess-like takeover plays of West Australia’s Robert Holmes a Court.

Elliott’s power peaked about this time. He was thought to be worth $100m. He owned rather than managed massive enterprises, and he commanded an everyday currency through his Carlton presidency.

On the side, he was Liberal Party president and angling – with some credibility – to be parachuted into politics and a prime ministership.

A high-powered cohort, including Lindsay Fox and Richard Pratt, quietly agitated for Elliott’s political ascendancy.

Then Treasurer Paul Keating said the ALP was dismissive of Andrew Peacock and his internal Liberal foe John Howard, but was concerned about an Elliott push.

“Running a big business is not the same as running a country,” Elliott explained, “but they have a lot in common”.

Elliott was hungry for more, but his timing was shot. In what he later acknowledged as a rare regret, he led a management buyout of Elders. It was 1989. The world was doomed to economic collapse. The titans, such as Bond and Skase, shied from the reckoning. Elliott’s Elders debts would isolate him from corporate power.

Receivers were appointed to his private company, Harlin Holdings, and the stigma of alleged underhanded payments – valued at $66m – would bathe the Elliott of the 1990s in debt, bitterness and legal bills he could no longer afford.

The tangled National Crime Authority case against him and others festered for years.

His Elders executive Ken Jarrett had pleaded guilty, turned witness against Elliott, and gone to jail.

Yet a protracted committal, followed by the trial itself, was derailed by a technicality.

Elliott got off, but his rage never dimmed. There was a high point in his gradual slide from bigness – the 1995 Carlton flag.

“I am seeking humility in victory,” he said.

“There is no doubt that this is the greatest club there ever was or ever will be. That’s the humility I’m looking for.”

SURFING LIFE’S WAVES

In the new millennium, Elliott was again taken to court, this time because his milling company, Water Wheel, traded while insolvent. A partner seeking $453,000 succeeded in bankrupting him.

Elliott was worth a few zeros less than he once was. Second wife Amanda left him after he sold their Toorak mansion without telling her.

He got convicted again of drink driving, a case of heightened interest after it was alleged he had called the arresting policewoman “girly”.

Elliott was philosophical.

“Life comes in waves, doesn’t it?” he said.

There was a softer side, a kind of loyalty from ex-wives who remembered better times.

Son Tom spoke of being raised by his mother – Dad was always away – but they grew closer, as shown in a weekly 3AW slot together.

Tom Elliott admired how his father always took “tough things in life on the chin”. He accepted his affectionate put-downs, too, as this on-air exchange in 2019 shows:

Tom: “Dad! Good evening!”

John: “Tom, that shirt is a disgrace.”

Tom: “I’ve got about 50 of them.”

John: “Well, don’t wear them when I come in here.”

Elliott has called his five children his greatest legacy. He had four rules for them, he once said. They should vote Liberal, barrack for Carlton and do their best. When they married, they had to ensure their partner barracked for Carlton, too.

Elliott once boasted that his parents had lived until their 90s. “I tell my kids that illness is in the mind,” he said in 2015. “If you think you’re sick, you will be.”